406 to 452

Welcome back everyone. I’m sorry about the interruption in service. There have been a lot of things happening IRL that have made it difficult to focus on putting out Podcast episodes. And to be honest, reading back over older episodes, I realized that I had lost some spark, wasn’t having as much fun doing these, and that it was starting to show. I didn’t want to put all the time into producing episodes that weren’t as good as I wanted them to be, or as good as you all deserve, so it was time to take a break and have a think. I also reached the end of a batch of sources, and had to catch up on reading.

But now I’m back, and let me offer a heartfelt thank you to all of you who left comments or sent emails while I was gone. Your support and patience have been amazing and an important motivation for me to work hard on coming back, so thanks to each and every one of you; in this little one-seater plane of an operation, you are all literally the wind beneath my wings. I could not do what I do without your support, and I am deeply and forever grateful.

All right, let’s all check our insulin levels, and get back into the swing of things.

We’re going to be switching gears. For quite a while we’ve been focused pretty intently on Belisarius and the wars in Africa and especially in Italy. That means that our focus has been relatively narrow, focused mainly on the Ostrogoths and Byzantines. Important, sure, but it means we’ve kind of lost sight of the rest of the Mediterranean and of the greater European world. So I’m going to be switching the focus westward, away from Italy, to Spain, and to the Ostrogoths’ cousins, the Visigoths. We’re going to be spending the next few episodes talking about the Visigoths and how they transitioned from a kingdom centered on Toulouse in southern Gaul, to a kingdom very firmly associated with Spain and Portugal.

I may have mentioned it before, but a while back, I went to see Mike Duncan speak in the back room of a coffee house in Milwaukee. If you’re a fan, you may remember him announcing that event, as the first of a run of personal appearances he was making. As a very small part of that presentation, he had a couple words about principles that guided his writing. Namely, “every sentence is about one thing, every paragraph is about one thing, every episode is about one thing”. Try as I might, I can not seem to master that last piece of advice, and in order to set the stage for the Visigothic kingdom, this episode is about three things.

First, I’ll talk about the history and development of Roman Hispania; what are we starting with, how was it organized, what did it produce? I feel like I could have done a better job of this kind of thing in past episodes about both Italy and Gaul, so I’m aiming to correct that going forward. Nested inside there is some information that isn’t strictly relevant to the history of the Visigothic kingdom, but it’s the kind of thing I stumbled across and couldn’t possibly leave unshared. Second, I’ll review a little bit of the history we’ve already covered as it applies to the region, namely the upheavals of the fifth century, up until the Visigoths were contracted to clear out the other barbarian tribes making trouble. Third, I will briefly talk about the sources we’ll be leaning on for all of this. There aren’t many; there’s no Priscus or Procopius around to give us a ground-level tour, and so reconstructing the chronology and narrative of the vIsigothic kingdom is a tougher nut than the Ostrogothic kingdom was..

Before we really get going, a quick note on geographical nomenclature. The temptation is to just say “Spain ” and be done with it, but that leaves out Portugal, and since there was no distinction yet between the two territories, that won’t do. The Romans called the whole region from the Pyrenees to Gibraltar “Hispania” and then subdivided it into smaller provinces, which I’ll get into in a minute, so Hispania is the word I’m going to be using the most often going forward. All of it sits on what’s known as the Iberian Peninsula or Iberia, so I probably will use that as well, though the presence of Caucasian Iberia, way over at the Eastern end of the Black Sea, may cause some confusion for some. How about I promise that for the rest of this series, at least, I will never again refer to that other Iberia, okay? As far as other place names, I’ll keep to my usual practice of using the modern name for cities and settlements, unless it doesn’t make sense to do so. I do that for clarity, so that if you wanted to you could follow along on a modern map and not have to constantly google the Roman names of places, just to find out, oh, he just meant Barcelona, or whatever.

The Roman presence in the Iberian Peninsula began when they defeated Carthage in the Second Punic war, in 206 BCE, but it took two hundred years of brutal, frustrating, and often poorly recorded fighting to extend control over the whole region. The middle of the peninsula is mostly made up of a highland plateau, surrounded and cut across by mountains, with the highest and most rugged of these being the Cantabrian Mountains, along the north coast, a continuation of the Pyrenees. The geography meant that the interior was a patchwork of Celtic, Aquitanian, and older Iberian tribes, many of whom were fiercely hostile to Roman domination. Among these were the Vascones, the ancestors of today’s Basques, who like the Isaurians in the Eastern Empire were barely ever Romanized and will pop up from time to time as a thorn in the side of various rulers as we move forward. The campaigns were convoluted, and often effectively were counter-insurgencies, with all the sorts of atrocities that that kind of war tends to produce.A couple of famous names made their bones fighting the Hispanian tribes, among them Cato the Elder, a few Scipios, and Tiberius Gracchus, father of the famous Gracchi brothers.

Roman control was established first along the coast of what we now call Catalonia in the northeast, and extended gradually down the Mediterranean coast and up the Ebro valley before any substantial gains were made in the interior. It was only with the subjugation of the Cantabri tribe in 19 BCE, in the reign of Augustus, that the entire region could be called Roman. Even after this nominal conquest, the Iberian interior would be a source of uprisings and unrest for another century, particularly in the North, and Romanization was gradual and uneven. The greatest concentrations of Roman coloniae were in the Ebro Valley in the northeast, along the eastern coastline, and in the Andalusian Plain in the southwest. The central and northern regions, more mountainous and less fertile, were slower to adopt Roman character. Much like the Gallo-Roman culture and identity that developed further north, a hispano-Roman identity developed, with identification with Roman ideals and culture more pronounced at the top of the social scale, and a more localized popular culture among the less wealthy or connected.

In spite of the violence of Hispania’s annexation, by the time the Goths crossed the Danube, and we started our story, the region had been strongly integrated into the Roman system for over 350 years. Time and distance from the frontiers had made Hispania one of the safest, richest, and most Romanized parts of the empire.

In material terms, that Romanization took all the forms we’re familiar with, bath houses, theaters, arenas, aqueducts, et cetera. Urban life was as important in Hispania as it was anywhere else in the empire, with some of the major centers being Tarragona, Mérida, Cartagena, and near Seville. It all had its own Hispano-Roman flavor, just as the culture of Gaul had its own flavor, but it was no less Roman for that.

Initially the region was divided into three large provinces, but in 298 these were reorganized into five, as part of Diocletian’s reforms. These five would persist until the fall of the empire and beyond, so we may as well go through them. They were: Tarraconensis, in the northeast, including the Ebro basin and most of the mountain passes to Gaul. Carthaginensis, the largest, in the east and center and including Valencia, Castille, La Mancha, and chunks of several other modern provinces, Gallaecia was in the northwest, the most mountainous, and containing both the current Spanish province of Gallicia but also about the northern third of Portugal and a sizable chunk of Leon. Lusitania in the west, including the rest of Portugal plus a chunk of Extremadura, and Baetica in the far south, mapping roughly onto modern Andalusia.

Acquisition of resources had driven the Roman conquest, and in turn Hispania became a major economic supporter of Rome’s further conquests. The mines of the region were legendarily productive, and remained so throughout the Roman period. Gold, iron, silver, and copper were the most important, but lead, zinc, and mercury were also pulled from the ground in significant amounts. The mines, worked almost entirely by slaves, were owned by the state and administered mainly by equestrian families, who became enormously wealthy in the process.

This is where we reach some of that information that just cannot be kept to oneself, and it has to do with the techniques of ancient mining. Again, not strictly germane to our subject, but, well, just wait.

Various mining techniques had been developing since the bronze age, and it should come as no surprise that Roman engineers developed advanced strategies for massive extraction of ore. The oldest method of gold mining is placer mining – that is simply panning gold from alluvial deposits in rivers and streams. Logically, that gold had to come from somewhere, and it didn’t take long for people to recognize that it must have come from upstream, in the mountains. The larger deposits gave birth to the small bits that were washed down, and are thus called, mother lodes – that’s where that comes from. And the Romans developed an absolutely mind blowing technique for exposing the mother lode so it could be extracted.

In Leon, near the modern city of Ponferrada, is a geographic feature called Las Médulas. At first glance it resembles a collection of eroded volcanic dikes, but it is in fact the remains of the largest open pit mine in the Roman empire. Roman engineers, having determined that the mountain contained large veins of gold ore, set about cutting channels and tunnels over and through it. Once tunnels had been completed, five aqueducts brought water from higher ground all around the site, channeled into the tunnels and over the mountain’s surface, and washed most of the mountain away. I’ve posted images on the instagram page, it’s really amazing.

Pliny the Elder was a procurator in the area at one point in his career, and described the technique, calling it ruina montium – the wrecking of mountains. He also noted the horrible lot of the slaves who actually did the work, those who dug the tunnels lived for months without seeing the sun. Slavery in the mines was, in a very real sense, a fate worse than death, though more often than not, it was that too.

According to Pliny, the mine produced 20,000 Roman pounds of gold every year. At today’s prices, that would be about half a billion dollars per year. The mine was active for about 250 years, until it was finally exhausted and abandoned sometime around the turn of the fourth century.

Besides the mineral products, Hispania produced plenty of agricultural products for export that filled the purses of the elite. Hispanian wine was produced in quantities both to satisfy the local market and export to Italy at several different price points. Salted fish and garum also filled the holds of ships bound westward.

Probably the most important cash crop for Iberia though was olive oil. Olive oil was the … well, oil oil, of its day. It was used in food, of course, but also in lamps, as a skin treatment, in perfume, in medicine. Olives and olive oil were produced all over the peninsula, but the olives of Baetica, the southernmost of the Hispanian provinces, were especially well regarded. Olive oil was made in industrial quantities and shipped to Rome. The sheer size of the City at its height meant that it could never be fully supplied by its own hinterland, and required massive import networks just to stay functional. That brings me to another one of those fun facts that you cannot wait to share with as many people as possible once you learn it. Ancient economics is fascinating to me, turns out.

The liquid goods coming to Rome were shipped in ceramic amphorae, essentially giant clay vials, and once they were emptied they weren’t good for much, so they were broken and dumped. In Rome, just inside the Aurelian walls at the south end of the old city stands a hill, called Monte Testaccio, which is a landfill made almost entirely of these smashed pottery vessels, most of them deposited before around 200 CE. Today its base covers a little under 5 acres, and it stands 115 feet (35 meters) high. It was probably bigger in ancient times. That’s impressive enough, but to make it relevant to our current discussion, analysis suggests that of those millions of amphorae, 80% of them contained olive oil from Baetica. A river of greenish gold flowed across the sea, from Iberia to Italy, and the families that owned the olive groves became rich.

All throughout the Roman empire’s history, agricultural production was steadily consolidated into large properties that could produce crops on a commercial scale. Olive oil and wine especially favored larger producers, since both required equipment, storage space, and other capital outlays and startup costs that were much easier for the already wealthy. Smaller farmers were unable to compete, and were gradually forced to abandon their holdings or sell them to their wealthier neighbors. From there, they had three basic choices. They could join the army, though as we’ve seen, this option became less and less viable as the military’s makeup transitioned to primarily germanic mercenaries. Farmers might look to be hired by those wealthy landowners, though most agricultural labor was done by slaves, and there were few paying jobs available. The only other real option was to immigrate to the cities and hope to find work there. This happened across the empire, but especially in those regions, like HIspania, with heavy commercial farming.

The feedback loop is pretty obvious. The rapid growth of the cities placed massive demand on the countryside to feed and supply them, enriching the landowners and enabling them to continue expanding their holdings, which in turn continued to drive immigration to the cities. These trends were ongoing throughout the history of the empire, increasing inequality across the board. Learned aristocrats continuously bemoaned the demise of the simple farmer-soldier on whom the old Republic’s greatness had been built, while simultaneously managing their estates in a way that made it impossible for them to exist.

The backbone of these large estates were the villas. Today we think of these as luxurious country houses, like Hadrian’s famous villa at Tivoli. But it is a mistake to think of a villa as the rural equivalent of a townhouse. Villas were engines of agricultural production. The main house may be luxurious, with all the amenities that a senator would expect, but it was surrounded by quarters for the slaves and overseers who worked the fields and storage buildings for their produce. They were businesses, and they were run like businesses. Archaeology shows what amounts to small towns clustered around the villas, housing the owner’s employees and dependents, along with livestock and equipment. Villas are found all over Spain, with particular concentrations right where you’d expect them from what I’ve already said, in the wine and olive producing plains of Andalusia, formerly known as Baetica.

Wealth and peace meant that when senators contemplated retirement, Hispania was at the top of the list for many who sought a quiet life.

The looming chaos would thus come as an especially nasty shock.

The first sign of trouble arose from that habitual passtime of late Roman generals: Civil War. The barbarian invasions across the Rhine in 406, along with the emperor Honorius’ apparently insufficient response, led the men of the field army in Britain to acclaim their commander as emperor Constantine III. He led his army across the Channel into Gaul to deal with the situation. He was at least partially successful, but was unable to expel the barbarians from Gaul. As emperor though, he wielded power over Gaul and Hispania, and after an unsuccessful attempt to dislodge him, Honorius was forced to recognize Constantine III as co-emperor. Hispanian nobles, probably at the instigation of Honorius or his magister militum, Stilicho, rose up against Constantine’s rule, and he sent a general named Gerontius to quash the rebellion.

Gerontius was successful, but betrayed Constantine and set up his own candidate as emperor. Sources here are divided about what happened next. Either Gerontius was distracted by the civil conflicts and left the Pyrenean passes undefended, or Gerontius actively invited the armies of Vandals, Alans, and Suevi roaming Gaul to come and support his rebellion against Constantine. Regardless, the barbarians crossed into Hispania in 409, either on September 28 or October 12. The sources are divided on the date, though everyone agrees that it was a Tuesday. These bands reached a working agreement to fight for Gerontius against Constantine. At the same time, rebellions in Britania and northern Gaul reduced Constantine’s “realm” to just central and southern Gaul, and left him vulnerable. Gerontius crossed back into Gaul with his barbarian troops, met Constantine’s son in battle and killed him, then marched on Constantine’s capital at Arles. At the same time, Honorius had named Constantius his new magister militum, and he was also advancing on Arles. A large part of Gerontius’ force deserted him and joined Constantius; he returned to Hispania and committed suicide.

That left the barbarian armies that had formed the core of Gerontius’ army without a commander or patron, and they were thus forced to make their own arrangements, and in this case, as we have seen so many times, that meant roaming the countryside, taking what they needed by coercion and force from the local population.

It’s important to remember, I think, that this kind of expropriation was just as much an act of desperation on the part of the raiders as it was a hardship to the raid-ees. While they were organized as military entities, the barbarian armies were complete communities, with wives, children, and elders included, and needing support. While there were probably folks who enjoyed the violence for violence’s sake, most ultimately were seeking the means to feed their families. That was a powerful motivator to seek stable situations, random banditry was not sustainable long term. We’ve seen this dynamic before, with Alaric and his Visigoths, for instance, and it meant that the local elites of Hispania had their own bargaining chip to set against the barbarians’ violence. Gradually, the groups found themselves a place in the landscape of Hispania, many of them ultimately making themselves the de facto political power brokers, or at least major players.

These original (so to speak) barbarians came from four main groups: the Suevi, the Alans, and the Siling and Hasding Vandals. The Suevi made themselves masters of Gallaecia in a kingdom that would last nearly a hundred years, though its borders expanded and contracted more or less constantly. The Vandals and Alans meanwhile made deals with the local power structures – essentially protection rackets that kept everyone fed, but did nothing to ease resentments of the locals who saw their hard earned produce (or potentially exportable trade goods) disappear into barbarian stomachs. Sources are extremely sketchy about how all of this played out or the exact relationships between the various tribes and local authorities. They are universally agreed, though, that none of it was good for the general population. Hydatius wrote that “The barbarians who had entered into the Spanish lands engaged in plundering and hostile slaughter. Pestilence played its part no less effectively… [the next year] While the barbarians raged through the Spanish lands, and the evil pestilence was no less vicious, the tyrannical exactor plundered the wealth and substance found in the cities and exhausted the soldiers. A horrible famine took hold, such that human flesh was devoured by the human race because of the intensity of the famine.” (al-Tamimi 2023)

That’s two episodes in a row with references to cannibalism, sorry about that.

This semi-anarchy continued for years, with the arrival of the Visigoths in the northeast only contributing to the chaos. The Visigoths initially were firmly in the underdog position, as they had just been forced to evacuate Italy and were penned up in Barcelona under Vandal siege. But their fortunes were reversed in 416. Constantius, having seen off Constantine III and another usurper called Jovinus, recruited the Visigoths as allies in his efforts to reassert Roman dominion in Hispania. With Roman material and possibly naval support, the Visigoths exploded out of the Northeast and fought a series of campaigns against the Alans, Vandals, and Suevi. The Siling Vandals and Alans suffered heavy defeats, and the Suevi lost at least one king, though their kingdom remained in the northwest. The Hasding Vandals, under the leadership of Guntharic, may have actually fought as Roman allies, which would explain their emergence as the dominant Vandal band. After three years of conflict, Constantius ordered the Visigoths to halt their campaigns and withdraw back to Gaul, where, as we know, they were granted permanent residence in Aquitaine.

By Bernd Gährken – http://www.astrode.de/sfth/sfth2009.htm, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=125868010

Constantius may have worried that the Visigoths would make themselves too powerful to control in Hispania, or he may have believed that the other tribes were sufficiently suppressed, and that the Visigoths would be more useful in controlling bagaudae revolts in Gaul. He didn’t seek the final elimination of the Vandals, etc, because he probably wanted to keep them around as potential federates, just with a clear idea of who was really in charge. It may have ultimately been a combination of all these factors.

By 418, there seems to have been a governor again, as well as an “official” field army in Hispania. None of the barbarians groups had been exterminated, and Constantius seems to have been perfectly content to have them available as recruiting pools, as long as they were slotted into the imperial apparatus. The major change that had been wrought by the war was the breaking of independent Siling Vandal and Alan power, and those bands were absorbed into the protection of the other tribes, some to the Suevi in the northwest, some placing themselves under the protection of the Hasding Vandals. The Alans offered to recognize the Hasding king Gunderic as their king, and the union of Vandal and Alan was achieved that would endure all the way to Belisarius’ African war.

The peace didn’t last long. By 422, Gunderic was fighting the Suevic kingdom for territory in Lusitania. He was successful, and before long the Vandals were once again a threat to the Roman order in Hispania. The details of the various battles he fought against the Romans and their Gothic and sometimes Suevic auxiliaries are unimportant right now, but two points are worth pulling out. First, according to Hydatius, in the course of the fighting, Gunderic sacked Cartagena and twice sacked Seville. Siegecraft was well within their competency. Secondly, this period is when the Vandals discovered boats, launching amphibious raids on the Balearic Islands and the coast of Mauritania. And if you remember, in just a few years, Vandal pirates will have the whole Mediterranean by the short and curlies. (Resisting the urge to make a manscaped joke here.) But at the moment, the Roman authorities were bringing in Visigothic auxiliaries to once again force the Vandals into subservience, and the pressure was building.

Gunderic died suddenly in 428, to be succeeded by his half brother, Gaiseric, with whom we are of course already familiar. Gaiseric must have already been planning for his next move, because it was just one year when he gathered up all the Vandals and Alans who would follow him, acquired boats, and crossed the Straits over to Africa.

The departure of the Vandals opened up a space for the remaining powers to fight over. Initially the winners were the Suevic kingdom in Gallaecia, who rapidly pushed their influence southward into Lusitania. For a time, they set up their capital at Mérida, but that would be the greatest extent of their kingdom. The expansion was halted in 452 when an agreement was reached with Valentinian III. Nothing specific is known about this agreement, other than it left pretty much the entire west of Hispania under the military authority of the Suevi. We’ll talk more about them in the next episode, since I’ve been largely ignoring the Suevi, and it’s high time they got their due.

Meanwhile, the imperial relationship with the Visigoths carried on under Theodoric II, as the Visigoths were given responsibility for maintaining authority in southern Gaul, based in Toulouse, as we know. That relationship would continue, though contentiously, as we’ve heard already, before reaching a true breaking point under the leadership of Theodoric’s successor, brother, and murderer, King Euric. The two great powers of Southwestern Europe were now the Suevi and the Visigoths, both under the nominal umbrella of the Roman empire, but both accruing greater and greater independence and ambition. Meanwhile, a range of small-time Hispano-Roman warlords staked their own claims in the gray areas of Hispania. The struggle over control of the riches of Iberia will pick up there next episode.

Since we’ve got an idea of what we’re starting from, let’s take a look at our historical sources for what happened next. We should all be used to me saying that the written record is spotty, but I’m going to say it again. Three chroniclers constitute the core of the historical record, Hydatius, John of Biclaro, and Isidore of Seville. Between the three of them, we have relatively close-up coverage from the early fifth century through around 624, as well as a kind of nice progression of a society and region gradually working its way out of chaos. Hydatius is our earliest source, and I’ve mentioned him briefly before. He was born sometime around 400 in Gallaecia and served as Bishop of what is now Chaves in Portugal. His chronicle is largely a record of contemporary events, which is great, though he did not have the up-close-and-personal perspective of Procopius. Like Geoffrey of Tours, Hydatius’ episcopal position meant he had to deal directly with the changing power structures around him, especially the Suebic kings who came to rule Gallaecia. Some scholars have noted that his chronicle is idiosyncratic, strongly personal, and closely observed, though not immune from error. Hydatius is assumed to have died around 468 or 469, since his chronicle abruptly stops at that time. Hydatius clearly saw the barbarian invasions and occupations as signs of the end times, and we can trace the crumbling of Hispano-Roman culture through his work.

A century later John of Biclaro, the bishop of Gerona, began his own chronicle as a continuation of the work of African chronicler Victor of Tunnuna. John was a catholic bishop, but of noble Visigothic birth, which put him at odds with the Arian king Leovigild in his early career. His chronicle covers a relatively short span, from where Victor left off in 567 to 590, but those years happen to coincide with the official conversion of the Visigothic state from Arianism to Catholicism, and so is highly valued.

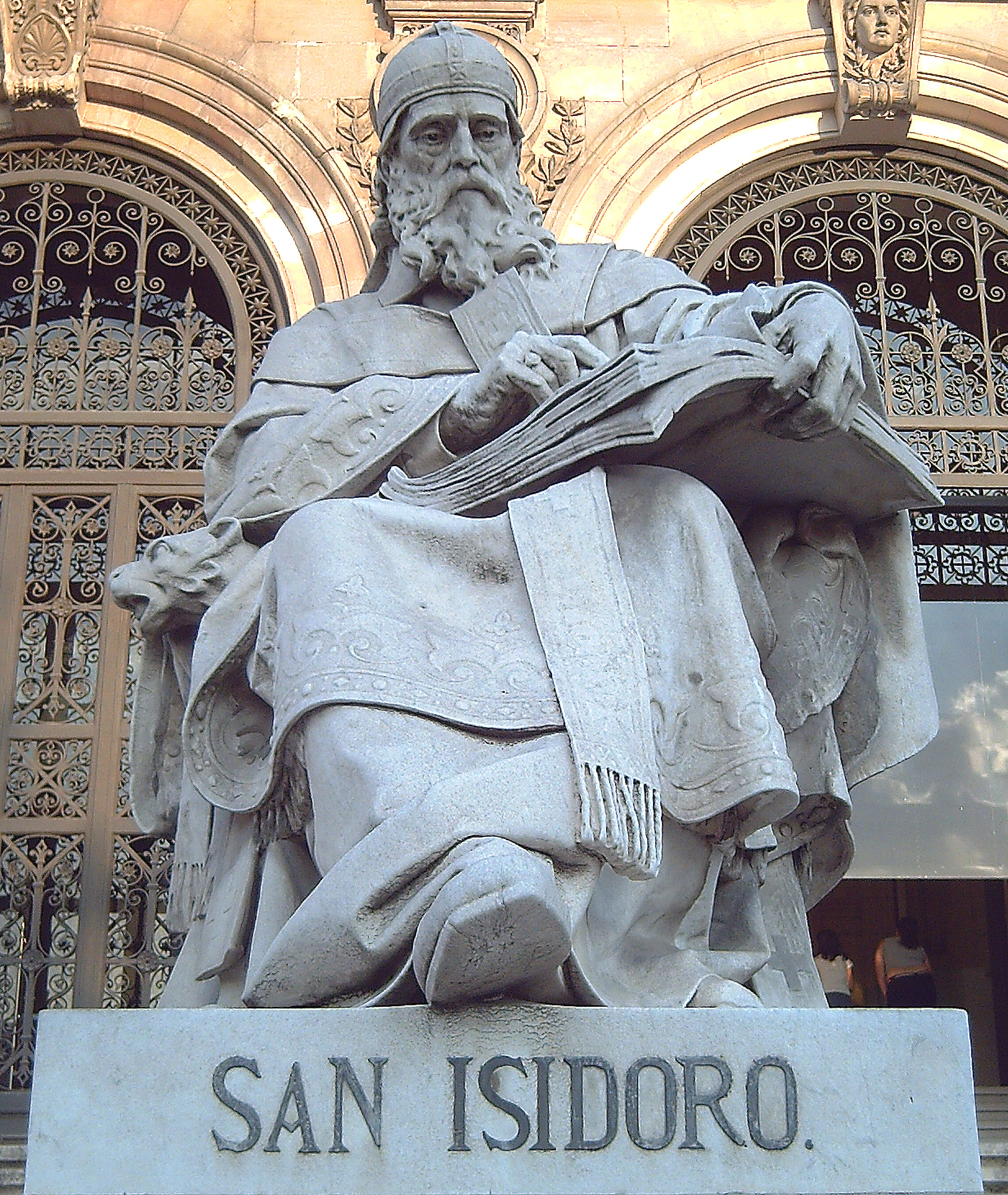

Lastly we come to Isidore, bishop of Seville, whose life could be an episode all by itself – and maybe will be at some point. Respected across Chrisandom for his writings, Isidore undertook the first effort by a Christian scholar to collect and present all the world’s knowledge in a single work, his Etymologiae, which also sought to place that knowledge in a Christian context. His work was copied and distributed throughout medieval Europe – popularizing the use of punctuation marks in the process for centuries after his death in 636. He was like a Christian Pliny the Elder, and like Pliny, transmitted a lot of scientific and medical ideas that seem deliberately made for modern readers to laugh at. For our historical purposes, we can be grateful to him for his Historia de regibus Gothorum, Vandalorum, et Suevorum, which draws from a wide variety of sources for the history of those three peoples, including Hydatius and John of Biclaro, along with other names familiar to us, like Orosius and Saint Jerome. In those cases he provides a useful summa of previous historians’ works. Between 590 and 620, his work is the only available primary source for the Iberian peninsula.

Isidore’s work was very much a part of an intellectual flowering that occurred in the Visigothic realms in the seventh century, and indeed these three historians provide a framework for the development of post-Roman civilization in Hispania. From Hydatius’ doomsday gloom to a belief in a bright Christian consensus, when Isidore could sing the praises of “sacred and always happy Spain, mother of princes and nations’. We’ll be dealing with the first half of that dichotomy in this series, up to the Visigoths’ final rejection of Arianism. For that is where we are headed. Chaos, followed by consolidation and the development of a new political entity, unified by a single church.

For most of this opening series of episodes, we’ll be in the hands of Hydatius, as he watches the world that had once been slowly collapse in front of him.

If you had told the Hispano-Romans living at the beginning of the fifth century that that’s where things were heading, it would have probably seemed like a cruel joke. We will start on that story next week, as the Visigoths are knocked back on their heels by the Franks, and struggle to form a new political entity and find a new home in Spain. Dang it.