518 to 532

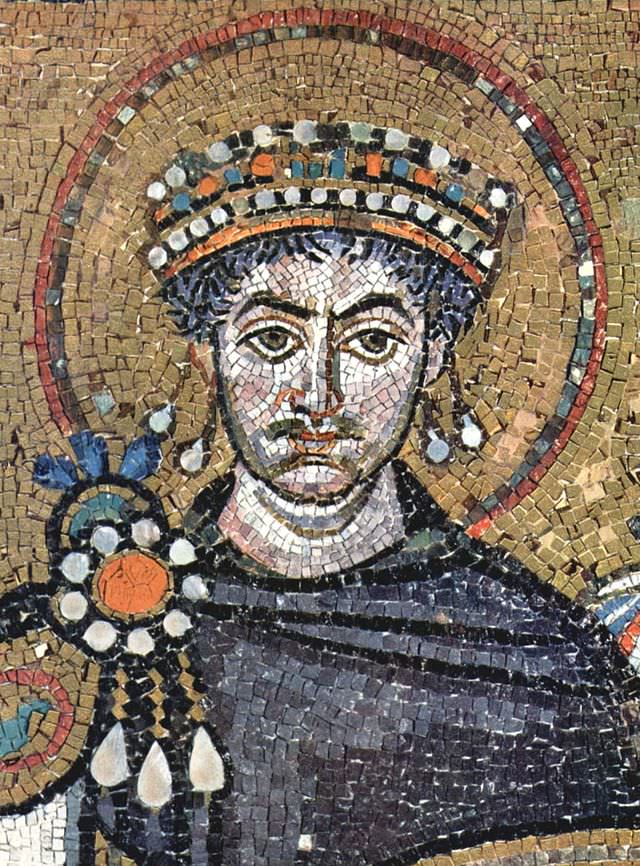

Justinian is probably the best-known “Byzantine” emperor to the general public. We’ll introduce the man and some of his circle, and explore some of the most important events at the beginning of his reign.

In mountainous Illyria, in a spot that Peter Heather describes as “miles from bloody anywhere,” was a small village called Tauresium. It was on the road between Naissus and Scupi – modern-day Nis and Skopje. Therefore, it had seen its fair share of armies passing through, both friendly and not. In the face of one of those unfriendly armies, a young man fled to the capital. He had the good fortune to find a place in a newly formed unit of imperial bodyguards and had the further good fortune to be competent and ambitious. Rising to the commander of the guards, he married, acquired wealth along with his position and prestige, and sent for the family he had left behind to come and join him and benefit from his success. One of these relatives, the son of the commander’s sister, stood out as an equally driven and intelligent young man, and the commander made sure he got the best education that money could buy. And when that was done, a plum job in the commander’s unit.

When the emperor Anastasius died in 518, fate, along with a well placed bribe, saw the imperial diadem pass to the commander of the guards – who became Justin I. His well-placed nephew, at birth named Flavius Petrus Sabbatius, took a new name in honor of his esteemed patron – Justinianus.

A rumor floated around Constantinople that Justin was in fact illiterate, and had been a swineherd before he arrived in the city, so it wasn’t surprising that he kept the well-read and energetic Justinian close to him throughout his years at the top. Justinian’s first promotion was to comes excubitoriae – the command position that had belonged to his uncle. Whether the rumors about Justin’s background were true or not, it was certainly the case that Justin’s marriage had produced no children, so it was equally unsurprising when Justinian was promoted again, first to caesar in 525, then co-emperor in 527, just five months before Justin died, in September of that same year.

Justinnian would rule the Roman Empire for 38 years, and was behind so many projects and achievements, that it seemed even longer than that. His was the third longest of any imperatorship, behind only Augustus and Theodosius II, and for impact, he’s easily in the top five – maybe even top three. I’m curious to see whether any of you will call me on the technical quibble that lives in that statement.

At the end of the last episode, I described Justinian as a bowling ball ready to destroy the carefully laid table of the Vandal kingdom. In retrospect, the metaphor doesn’t really work for the Vandals, but man does it ever for Justinian.

There are a zillion places you can go to learn about the incident and outcomes of Justinian’s reign. The obvious place to start of course is the oft-mentioned History of Byzantium Podcast by Robin Pierson, who devotes 16 episodes to the man and his times. I’m not going to go into nearly that much detail, since I’ve said over and over again that I’m not going to spend that much time on the Eastern empire, but I can’t not talk about him.

I’ve already given the outline of Justinian’s rise to power. The rest of this episode is going to be about two things, a couple key events of Justinian’s first five years in power, and secondly, introducing the people who surrounded Justinian and who will be a part of our story for the foreseeable future.

Justinian’s first language was Latin, in fact he apparently never shook the accent, though as he spent most of his adult life working and speaking in Greek. The Illyrian countryside where he was born had been most often within the sphere of Rome rather than Constanitnople, and nostalgia for the old days of the united empire seems to have had at least some effect on Justinian’s worldview. If I have space at the end of this episode, we’ll try and explore the tricky question of the Eastern empire’s attitude toward its former territories in the West.

The word that comes up most often in modern work about Justinian seems to be “energetic”. “The emperor never sleeps” was a common saying during Justinian’s reign, and he could be found wandering the palace or working late into the night. The list of his projects could fill up the rest of this episode, and indeed some of them will fill up the next several episodes. The great church of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople is without question the centerpiece and most enduring monument to Justinian, but he funded dozens of churches all around the empire, updated and improved the capital’s harbors, supervised the codification of Roman law, and began the construction of a new city (named after himself) at the site of his birth. No one, even his most ardent critic, could have accused him of being lazy. He was apparently approachable and friendly, though Procopius accuses him of being deceitful in the extreme and petty (which to me, just proves he was a politician). Probably most importantly, he was an excellent judge of talent, and surrounded himself with the most competent men available to execute his projects. Competent, but not necessarily the most ethical or diplomatic.

When he came to the throne, Justinian was full of ideas, but first on the agenda before he could make headway on any of them, he needed peace with Persia.

I haven’t talked about Persia in a long time, and I’m only going to do enough to bring us up to date right now. War with Persia had been a major distraction for Constantinople, with conflicts over the control of border states like Armenia and Iberia a major issue, as well as Roman forts in parts of Mesopotamia that the Persians saw as their own. Tensions in the region had been building through most of Justin’s time in power, with war breaking out into the open in the last year of the old soldier’s reign. At the beginning of Justinian’s reign, the Persians were in the driver’s seat, but a couple of key victories shifted the momentum to the Roman side. One of those victories, at Dara in 530, was thanks to the efforts of a young general, named Belisarius, one of those men whose talent Justinian recognized. The next year, Belisarius was defeated by the Persians at Callinicum, putting off a resolution to the conflict for another year. Belisarius was removed from his post and summoned back to Constantinople to face an inquiry. With him through all of this was our buddy Procopius, serving as an advisor to the general. While it seemed that Belisarius was about to be read the riot act, it’s likely that Justinian wanted him close for other projects away from the Eastern theater, and was playing his cards close.

In the end, peace with Persia came about thanks to the death of the Persian king of kings, Kavad, and the succession of his son Khusrow. Khusrow was familiar to Justinian; once upon a time Kavad had proposed that Justin adopt Khusrow to secure his position against rival claimants to the throne, which would have made him and Justinian brothers. The scheme came to nothing in the end, but it meant that there were personal connections between the two rulers. Khusrow accepted a massive payment of 11,000 pounds of gold from Justinian to end the war and sign what was known as the Treaty of Eternal Peace between the two empires. Eternity apparently equalled eight years, but it was enough to free up resources for Justinian’s other projects further west. It wasn’t a universally popular peace, many grumbled that it looked an awful lot like the Romans paying tribute to the Persian empire, which would imply Persian superiority. Not a concept the Roman mind was comfortable with.

I know what you’re thinking: 11,000 pounds of gold is almost triple the largest payment ever made to Atilla the Hun, almost 900,000 gold pieces. Where exactly was all that gold coming from?

Justinian’s eye for talent comes into the equation again. He brought new men into the civil side of government as well as the military. Most famous among these were Tribonian and John the Cappadocian. Both were important in Justinain’s great codification of Roman Law, which we’ll talk about another time. But at the time, they were both more infamous for their role in tax policy. Justinian needed money, and these two were going to get it for him, by a combination of ruthless economizing and equally ruthless tax collection. John was especially notorious in this, more than willing to use violence to extract every available denarius from his targets. Procopius, in the Secret History, blames Justinian for the cruelty and dishonesty of his subordinates, on the principle of “corporate culture starts at the top ”. Both Tribonian and John would face popular outrage, which we’ll talk about shortly, but their exactions were key to putting the empire on more stable fiscal footing than it had been.

Before we get to that popular outrage, we need to talk about Theodora.

Theodora leads us into the dangerous waters of Procopius’ Secret History, where it’s hard to know what’s true, what’s malicious, and what’s a joke.

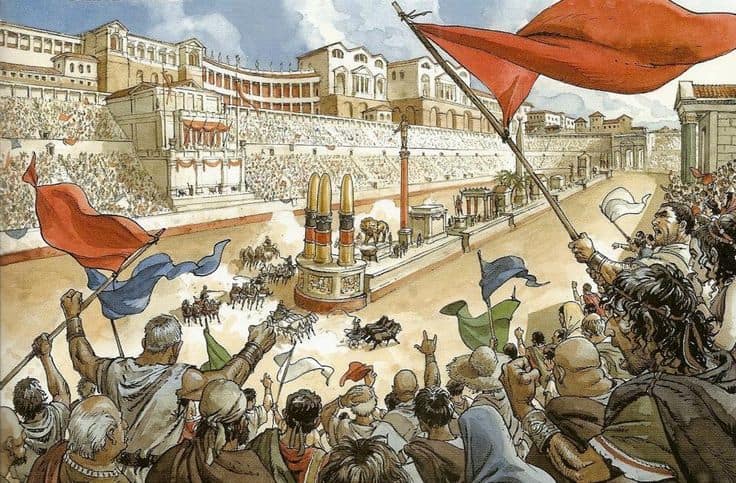

Theodora, like Justinian, was a climber, and a troublemaker. She was the daughter of an animal trainer, who provided animals for entertainments at the Hippodrome in between chariot races. When she grew up, she had also entered the entertainment business as well, as a dancer, and if we are to believe Procopius, as a prostitute. Really, that’s not unlikely, the line between the performing arts and the um performing arts was pretty much invisible. Procopius ascribes all kinds of exploits to her, none of which are appropriate for a family show, and and an unknowable portion of which are probably fabrications. What is certainly true is that she was not considered an appropriate match for young Not-Yet-Emperor Justinian, but the young noble was hooked. He prevailed upon his uncle to change the law to allow him to marry Theodora, and the lady skipped over the many rungs of the social ladder between circus and palace in a single bound. She was well known for her influence over Justinian, and was in no way circumspect about her opinion. She feuded with his advisors and would take any opportunity to undermine them that presented itself.

Once she was empress, Theodora and Justinian set about erasing her previous reputation. She became almost as much a face of the regime as her husband, appearing with him at state events as an equal, and insisting that she be treated with the same level of deference. Outwardly, this shored up the dynasty’s legitimacy, presenting the couple as God’s chosen leaders of the one and only Christian empire. But it bred resentment among the hereditary nobility who were well aware of Theodora’s, and indeed Justinian’s backgrounds.

That resentment was especially dangerous because of the way Justin, and then Justinian had come to the throne. Justin had not become emperor because Anastasius had no remaining relatives, he had just been the most adroit of the competitors on the spot at the time. There were still plenty of members of Anastasius’ dynasty hanging around, in particular the late emperor’s nephew Hypatius. Meanwhile, the diems – the factional supporters of the various chariot racing teams – chafed under the exactions of the new civil administration and resented the uneven implementation of Justinian’s legal reforms. The diems were kind of a combination fan club and street gang, often led by young noblemen with too much time on their hands. Before he became emperor, Justinian had been a supporter of the faction known as the Blues, but that support did not translate into preferential treatment once he came to power, and the Blues resented it. Their rivals, the Greens, had meanwhile not forgiven the emperor’s earlier favoritism to their opposition. Elements within the palace seem to have stoked these resentments. As the Persian war dragged on, tension rose. When it ended under terms that could certainly be spun as a humiliation, the situation only worsened.

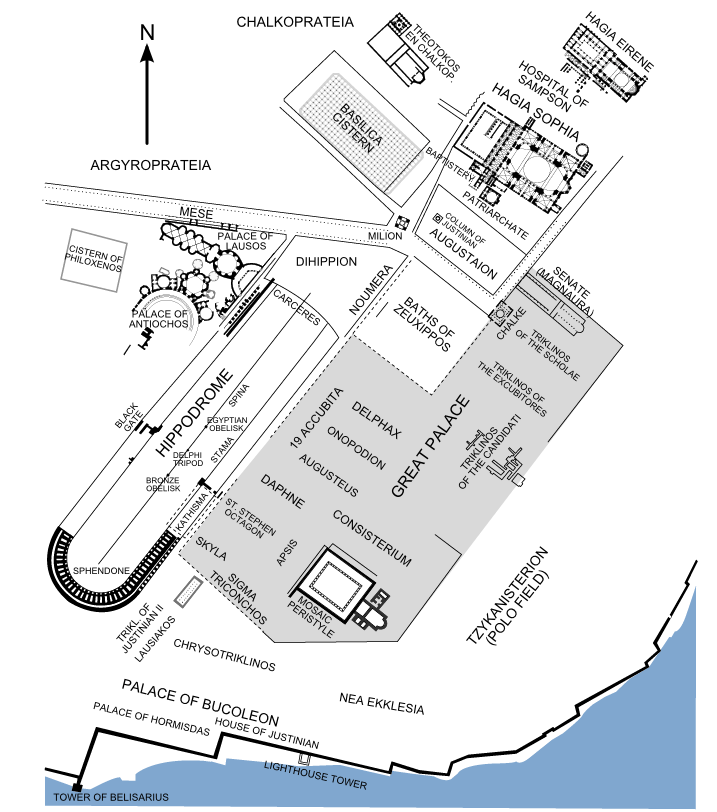

At the races on January 13, 532, things turned ugly. The Hippodrome abutted the palace, so that Justinian could enter his box without going out on the street, and he was in attendance for that day’s races. Regularly showing himself to the public was one of the ways the emperor demonstrated that he was in good health and control of the empire, and gave the populace an opportunity to make their feelings about the regime known.

Right from the start, the January crowd was hostile, shouting abuse at the emperor and empress. As the day progressed, their mood only deteriorated. Instead of the usual factional chants, the whole crowd began chanting “Nika, Nika” which was the Greek word for victory, and which gave the Nika Riots their name. The end of competition was quickly followed by violence. Stones and refuse were thrown at the emperor’s box, and he and Theodora were forced to retreat inside the palace.

The crowd streamed out of the hippodrome and took control of the streets. Fires were set around the city, and the imperial guard was helpless in the face of such mass opposition. Fire was the nightmare scenario for all ancient city dwellers, and this one spread quickly. The great Hagia Sophia church, the baths of Zeuxippus, and part of the palace were all consumed, along with the collonaded marketplace of Constantine and many private dwellings. “Fire was applied as if by the hand of an enemy” as Procopius puts it.

The rioters demanded the removal of John the Cappadocian and Tribonian; Justinian caved, and the two were removed. They, along with many others, barricaded themselves in the palace for safety. The specificity and clear targeting of the demand was the first sign that these riots were receiving direction from somewhere inside the bureaucracy, and suspicions inside the palace grew. Some of the rioters indicated that they would accept nothing less than Justinian’s abdication, in favor of Hypatius. Hypatius himself went to the emperor to personally assure him that he had nothing to do with the riots, and had no interest in the throne. Justinian appears to have believed him, not that it did either of them any good. The atmosphere inside the palace became increasingly poisonous, and a siege mentality grew. Meanwhile, the city burned.

Justinian and many of his advisors were prepared to abandon the city, and presumably the throne, in the face of such intractable opposition. Boats were prepared, and were ready to take them away from the palace into safety. But Theodora refused. She had come up from nothing to greatest possible wealth and influence, and wasn’t about to take a single step backwards. According to Procopius, she shamed the cowardly men; “For one who has been an emperor, it is intolerable to be a fugitive. May I never be separated from this purple, and may I die on the day that those I meet do not call me mistress. If you wish to save yourself, Emperor, it is not difficult. We have money, here is the sea, there are the boats. However, consider if once you are saved, you will not come to gladly exchange that safety for death. For myself, royalty will make a fine burial shroud.”

The lady was not for turning.

It was enough. The court began to debate among themselves how to bring the riots to an end. It was clear that appeasement was a fool’s strategy, the mob would not be satisfied until Justinian was dethroned, maybe dead. Some of the palace guards had fled, some had joined the rioters, but there were enough left that a military solution wasn’t out of the question. Soon a plan was in place, it was a terrible plan, in the old sense of that word, that would hopefully not only bring an end to the violence, but remove the potential for future disturbances. And it happened that Justinian had just the men for the job.

Belisarius was in town, having been recalled from the Persian frontier, along with another general named Mundus. Mundus was by birth a Gepid, or a Hun, a Goth, or maybe all three, sources are divided – identities in the Balkans were always fluid, as we’ve heard. What was important is that he had spent the last three years fighting for the Romans, first in the Balkans then in the East, and had demonstrated his loyalty and competence in both theaters. The last part of the puzzle was a eunuch named Narses. Narses had already been around forever, he had been instrumental in Justin’s accession, and was well-versed in the arts of palace intrigue and subterfuge. He seems to have known everyone, along with every pressure point in the imperial apparatus. Narses was given a substantial quantity of gold, and told to slip out of the palace and find the leader of the Blues. Would the gold, along with the old tie between them and Justinian, convince them to hang back from the violence in the next few days?

The mob had seized Hypatius, and were going to crown him at the Hippodrome, whether he wanted them to or not. The large gathering and ceremony that would entail presented the government with an opportunity.

Justinian made himself scarce, allowing the crowd to believe he’d been cowed into accepting his overthrow.

On the day of the coronation, the hippodrome was full of people, mostly down on the floor of the track. During the ceremony, the Blues suddenly withdrew from the great stadium. Narses had done his work. Once they were clear, the generals made their move. Belisarius led a force of loyal guards out of the stands near the emperor’s box. The crowd vastly outnumbered them, but were mostly unarmed, entirely unarmored, and taken completely by surprise. Hemmed in by the stands, they turned and fled the advancing soldiers, only to meet Mundus and his force, coming the other way, from the main entrance gates. Belisarius and Mundus worked toward each other methodically, hacking and slashing indiscriminately. When they met in the middle of the hippodrome’s floor, Procopius tells us they were surrounded by 30,000 dead.

30,000 dead, out of a population of probably between 5 and 600,000. Imagine that in a modern city. My own local example, Milwaukee, is roughly similar in population. But while Milwaukee is spread out over about 95 square miles, the population inside the Theodosian walls occupied about 5.5 square miles, 14 square kilometers. The only modern city that approaches that level of density is Manila.

Between the fire, the violence of the riot itself, and the vicious repression, no one was untouched by Nika. Popular protest and indeed riot had always been a part of Constaninople’s popular political culture; the response to the Nika Riots tore the heart out of the city. No popular unrest would trouble Justinain again. He would rebuild the city, better than it had been before, but it all rested on the ashes of Nika.

The nobles who had participated in Hypatius’s coronation were identified, rounded up, and exiled, and poor Hypatius, though probably blameless, was executed as well. It was too dangerous to leave him alive as a symbol of resistance. The people who I’ve introduced in this episode, Belisarius, Mundus, Narses, John and Tribonian, will all be frequent guests of this show for quite a while, and it was the Nika riots that bound them together and made them the trusted core of Justinian’s team.

I’m putting a specific kind of spin on the outcome of Nika; that it freed Justinian’s hands to act as he wished, and in the long term that turned out to be true. But in the short term, coming as it did on the heels of a Persian peace that many saw as the shameful payment of tribute to an ancient enemy, the riot was a blow to the regime’s prestige. An emperor who reigned over charred rubble, and who paid his enemy to leave him alone, was hardly an emperor at all. Justinian needed a project that would restore his legitimacy, and restore the light of God’s favor to his imperial image.

Whether Justinian hit on the coming war in Vandal Africa – for that is where we are heading, dear listener – is a matter of historical debate. Peter Heather argues that the Vandal expedition presented itself as a solution to the legitimacy problem essentially as a whim of fortune; that Justinian had had no designs on such a re-conquest before the opportunity arose. Others have suggested that Justinian looked back at the united empire with nostalgia and was actively looking for chances to undo the humiliations of the last century. And what better way to restore his legitimacy, and his eternal legacy, than by restoring what had been lost? It’s unknowable, of course, and that’s why historians like to argue about it.

It gives me an opportunity to explore a question that hasn’t come up in a while. What did the fall of Rome really mean to those who lived through it? We’ve talked about it from the western, on the ground perspective. Certainly people were aware that an emperor had been deposed, they were aware that it came at the end of decades of instability and chaos. They had only to look out at their trampled fields and burned ships to know that it had gone down kicking and screaming. Sidonius Appolinaris even identified 476 as the year it all came to an end.

The east on the other hand, can seem oddly passive about the whole thing. During the years of crisis, there had been a handful of attempts to save the west, but other than the disastrous attempt to retake Africa in 468, most of these had consisted of declaring emperors and sending them to Italy, only to fail in the face of reality. Distractions from the Persians and from the Steppes can explain some of this, the East had its own problems. But once it had managed to stabilize itself, around Anastasius’ time in power, there were no concerted efforts to retrieve Africa, Gaul, or Spain in the name of Rome.

Part of this was cultural. Diocletian had divided the empire into East and West in 286, Constantine founded his New Rome in 330. By 527, when Justinian came to power, the East and West had been de facto separate entities for generations. Latin was still a language of government, but most people in the East spoke Greek, and the East had always had a cultural feel to it that was different from the West, even before the administrative split. It was easy for a citizen of Constantinople to go through life perfectly content that he lived in the richest and most powerful empire in the known world. Crisis, what Crisis?

The people who occupied the top jobs certainly were aware of what had been lost. They were brought up on the early history of Rome, Livy and Suetonius and so on, but that didn’t mean they necessarily had skin in the game. Rome had founded a great empire, things had changed, and now that empire no longer contained Rome itself, but that wasn’t the end of the world, the Sainted Constantine, in his wisdom, created a new Rome, right where and when it was needed. Most elites no longer had any kind of financial vested interest in the West anymore. There were refugees from Italy and Gaul and so on, but it had been fifty years now, most would have married into Constantinopolitan society and assimilated, the pressure to restore what they had lost was fading.

Diplomatically, the government in the East was mostly happy to keep up the fiction that the western kingdoms existed on sufferance, that they were all in fact viceroys for the emperor. The Germanic kings kept up their end of the charade because there was still prestige in the old titles the East could and did dole out. Consul, patricius, magister militum, and so on. Kings of the Franks, Ostrogoths, and Burgundians all accepted imperial titles with pride, and did their best to stay on good terms with New Rome.

So what was changing? I’ve already tipped my hand, Justinian is going to war in the west. Why now? It’s tempting to put it down to ego, and that may have played a part. Justinian was a man wholly comfortable with the idea of himself as God’s hand picked representative, and his self-regard seems to have had few limitations. But as we’ll see, the Vandal war didn’t start as a mission to restore what had been. I don’t have an answer to this question, yet, but with the ascension of Justin, Roman propaganda shifted toward a much harsher tone with regard to the western kingdoms. It’s in Justin’s reign that the first reference appears in a chronicle to 476 as “The Fall of the West”. (Sidonius’ earlier notation was in a letter, not official history.) The sense that something was wrong, that had to be righted, comes more and more to the forefront.

Part of it may have been religious. While Anastasius had been emperor, with his unorthodox, monophysite views, the separation of the Orthodox pope from the Eastern Patriarch had seemed bearable. In the orthodox mind, both the pope and the conventional Christians of the east suffered under heretical rulers. But once the ultra-orthodox Justin, and the equally conventional Justinian were in place, the Acacian schism was healed, and the situation changed. Now the east was united under one true faith, while the pope groaned in subjection to an alien, Arian oppressor. And how much worse was the fate of the inhabitants of Africa? The Arian king of Italy, Theodoric, could at least make a case that he was a civilized man.

Hostility to the western kings on an ideological basis was gaining ground in Eastern corridors of power. Justinian would give that hostility shape.

Next time we’ll hear about the first of Justinian’s wars of restoration, as Procopius accompanies Belisarius to tell us all about it.