December 533 to March 534

Things go from bad to worse for the Vandal kingdom.

Last time, I implied that Belisarius’ early victory at Ad Decimum wasn’t necessarily the end of the war, and was only the beginning of trouble for the Romans in Africa. I stand by that, but the truth is that most of the trouble would come after the war, and thanks to time restraints, after this particular episode. We’ll get to it, but for today, mostly we’ll watch as the sun continues to shine brightly on Belisarius’ face as he finishes what he started. Victory at Ad Decimum has come with surprising ease, and the Roman general set up camp outside Carthage, preparing to enter the city the next day.

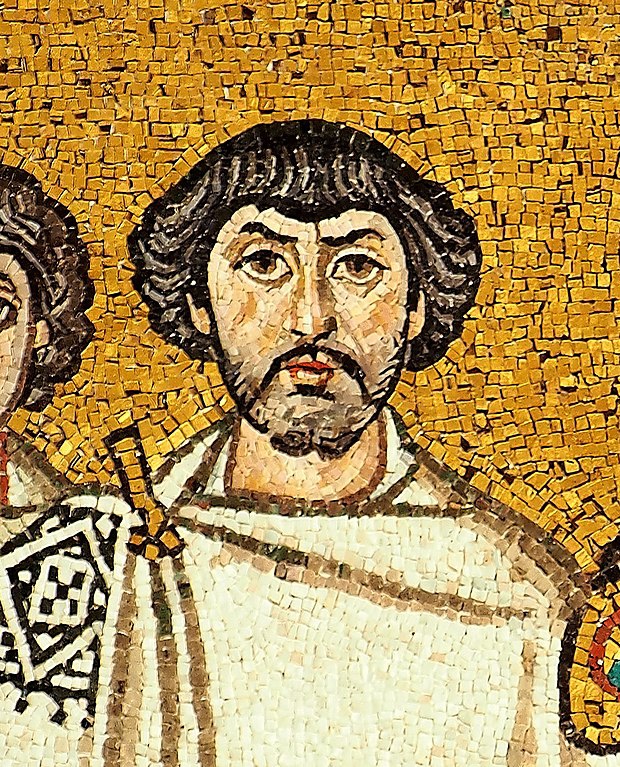

Belisarius was in his thirties at the time of the Vandal war, having been born sometime around the year 500, in a town called, confusingly, Germania. There are two possible candidates for where that was, one in modern Bulgaria, the other in Greece. There isn’t much known about his early life, he joined the army as a young man and found his way into one of the imperial guard companies that protected emperor Justin, where he would have had some early contact with Justinian. Around this same time he married Antonina, a friend of Theodora, Procopius says that she, like the empress, had been a woman of the theater- nudge nudge wink wink – and that she utterly dominated Belisarius. Overbearing wife or not, Early signs of quick thinking and an innovative outlook led to his promotion and deployment to east as war broke out against Persia in the later part of Justin’s reign. Belisarius’s first independent command saw him defeated by the persians, and indeed his first few set piece battles were far from glorious. But he was a daring raider, and he and his superior officer, Sittas by name, won some prestige back with successful plundering raids into Persian territory.

When Justinian came to power, he promotes Belisarius to overall command in the east, and won a brilliant victory at Daras in 530, which brought the Persians to the bargaining table, but the advantage was handed back when Belisarius was beaten by a Persian army smaller than his own at Callinicum. He had been out-generated by the Persian commander Azarethes, and was recalled to Constantinople to answer charges of incompetence, which were dropped just in time for him to help put down the Nika riots, as we’ve already heard.

In Carthage, the remaining Vandal officials were in a panic when news of their king’s defeat reached them. One man, in charge of a prison that housed several Romans Gelimer had been planning to execute, went to the prisoners and asked what they would give him to help them escape. After hearing their promises of wealth and other rewards, he told them to keep their goods, but swear to help him escape the retribution of the Romans, and told them the whole story of what had happened at ad Decimum. He added a dramatic touch by tearing away one of the window coverings of the cell and pointing out to the approaching Roman fleet. The prisoners agreed to do what they could, and he released all of them.

Meanwhile, Belisarius entered Carthage cautiously. He had no way of knowing exactly how he would be received, and was worried about walking into a trap. This caution was a feature of Belisarius’ leadership, he was never one to take unnecessary risks. But the Carthaginians, like all the other urban Africans he had encountered, were happy to open the gates. The Roman army had the unusual experience of entering an enemy’s capital in parade order and no violence. The city’s markets were open to feed them, and the inhabitants’ homes were open to house them. Belisarius himself took over the palace, sat in Gelimer’s throne and ate his food. It had to feel good.

The Vandals that did remain in Carthage fled to the sanctuary of various churches around the city. Belisarius pledged that they would be kept safe as long as they did not act against him. Not resting on his laurels, the general began the repair and rebuilding of the city’s walls, starting by erecting a palisade and ditch around the whole city. The walls were not in great shape, apparently, which may have been why Gelimer had sought battle outside the gates rather than hunker down in an indefensible city. The speed with which the palisade went up reportedly amazed the Vandals who saw them, but of course we, veterans of Mike Duncan’s history of Rome, know that putting up walls quickly is what the Romans did.

Belisarius was putting his resources into defenses because, in spite of appearances, the Vandals had not been decisively defeated at Ad Decimum. They had fled the field, but as another famous Roman had noted nearly four centuries earlier, he who fights and runs away, may turn and fight another day. If Belisarius wasn’t familiar with Tacitus directly, he certainly understood the sentiment, and Gelimer certainly did as well.

Gelimer had not been idle, he was holed up somewhere west of Carthage, and had been spreading gold around the locals. He placed a bounty on the heads of any Romans that ventured outside the walls. There were plenty who cashed in on the deal, but most of those killed were slaves and servants of the army, not soldiers. The actual fighting strength of Belisarius’ army wasn’t reduced much by the guerrilla action. Had they been out in the field on their own, then it would have been more of a problem, but with the city open, and a clear line of supply and communication by sea, Gelimer’s local partisans were little more than a nuisance.

Gelimer wasn’t depending on the locals though, he was gathering all the remaining Vandal forces he could to him, as well as any Moorish tribes he could convince to join him. There weren’t very many of the latter though. The Moors had for generations sought the prestige that came with imperial recognition. Many tribes would not recognize a leader who had not received his crown from the Romans. That had been an impossibility for the last hundred years or so, but now the Romans were here, and Belisarius was more than willing to dole out imperial recognition in return for the Moors’ material support. Most of the Moorish tribes that chose a side at all pledged themselves to Belisarius.

Gelimer also sought alliances elsewhere in the Arian world. Amalasuintha was out, she was too closely tied to Justinian, but the Visigothic king Theudis might be persuaded to join some kind of coalition. Actually, Gelimer’s emissaries to Theudis had left shortly before Belisarius arrived in Africa, but took so long to find the king, he had already heard all about the war and the fall of Carthage. He didn’t share his information, but refused the alliance, and suggested that the ambassadors return to the coast, where they would be sure to hear the news for themselves. It was embarrassing for the poor ambassadors, who sailed home and surrendered to the first Roman soldiers they came across. Gelimer would receive no help from Spain either.

There was one ace remaining up Gelimer’s sleeve. You’ll remember that one of the reasons Belisarius had been so successful so far was because of the revolt in Sardinia. Gelimer’s brother Tzazon had taken 5,000 vandals to the island to put down the revolt, and was quickly successful. While still in the port city of Caranalis, he heard of the Roman invasion force, and wrote to Gelimer to warn him. But the war had progressed so quickly, Tzazon’s messenger arrived after Carthage had already fallen. Meanwhile Gelimer had written to Tzazon with his own accounting of recent events, and a plea for help. Tzazon didn’t hesitate. He set sail and landed near the border of Africa and Numidia, marching to meet Gelimer at his base on the plain of Boulla, near the modern town of Jendouba, Tunisia. Procopius describes the brothers’ reunion, and it’s a great example of the classical style of history writing, so I’m just going to quote it directly:

“They reached the Plain of Boulla traveling on foot, and there joined with the rest of the army. And in that place there were many most pitiable scenes among the Vandals which I, at least, could never relate as they deserve. For I think that if even one of the enemy themselves had been a spectator at that time, he would probably have felt pity, in spite of himself, for the Vandals and for human fortune. Gelimer and Tzazon threw their arms around each others necks, and could not let go, but they spoke not a word to each other, but kept wringing their hands and weeping, and each one of the Vandals with Gelimer embraced one of those who had come from Sardinia, and di the same thing. They stood for a long time as if grown together and took what comfort they could in this. Neither did the men of Gelimer think fit to ask about [the revolt] … Nor could those who had come from Sardinia bring themselves to ask about what had happened in Africa.”

Allow me a moment to wax lyrical about Procopius. Other writers who we have already heard from on this podcast, would have recorded the tearful meeting of the brothers, but most of them surely would have used it to emphasize the emotional nature of barbarians, with their unmanly displays of emotion … but there’s no sobbing or wailing here, there’s silent grief, and a search for human comfort. Procopius could not have witnessed the meeting, and probably only surmised that it happened at all – it’s all a fabrication, in other words, but it’s the fabrication of a novelist, not a propagandist. This is the kind of empathetic, humanist approach to history – history that seeks to illuminate the human condition – that sets Procopius among the pantheon of great historians in the classical mold.

Gelimer moved to surround Carthage and set up a kind of siege. I say “kind of siege” because the Vandals watched the roads and took possession of the surrounding countryside as if they still were in power, but did not loot the precincts, or set up a strict cordon sanitaire around the city. Their most significant move was to cut the aqueduct that supplied Carthage. The aqueduct was built during the reign of Hadrian, and had been one of the longest in the empire, running an impressive 82 miles – or 132 kilometers, for the 40% of you listeners who have abandoned good traditional measurements and remain in thrall to the French. The aqueduct would be repaired after the war with the Vandals ended, and remain in use at least until the 13th century. Today, parts of the old channel still carry water to Tunis, albeit via modern piping.

When it became clear that he could not provoke Belisarius out to fight, Gelimer attempted to sow disharmony within the city. In addition to hoping that some element within Carthage would begin a rebellion – maybe some of those who had adopted Arianism – Gelimer also sent messages to the Huns Belisarius had brought with him. The Huns were a likely target for subversion, since they were the least willing of the Roman allies. Some claimed they had been brought into the invasion force under false pretenses, and they generally kept to themselves in their own camp, rather than mingling with the rest of the army. The Hunnic leaders responded favorably to Gelimer’s overtures, and assured him that when the time came, they would turn their coats.

Belisarius, though, had his own sources of intelligence, mainly deserters from Gelimer’s camp, and so heard about the planned treachery. He had little tolerance for disloyalty, and punished the few traitors among the Cartheginians mercilessly (impaling was the favored method of execution), but he couldn’t afford to alienate the Huns and push them into a mutiny. So he courted the Hun leaders with gifts, and gradually convinced them to confess to the contacts they had had with Gelimer. THe problem, the Huns explained, was that they had no faith that any outcome of this war would be in their favor. They feared that if the Vandals were defeated, they would be forced to settle in this distant territory, rather than returning to their homes, and were additionally concerned that they would not receive their share of the plunder if they did return home. Distrust between the two peoples remained high.

Belisarius assured them on his honor that as soon as decisive victory was achieved, the Huns would be free to return to the steppes, and that they would take with them their fair share of the plunder. The Huns swore to stay loyal, and Belisarius was forced to accept their oath (what other choice did he have?) but among themselves the Huns agreed that they would hang back from any future engagement, and only fight for whoever looked most likely to win.

Once the repairs to Carthage’s walls were complete, and Belisarius was confident that no fifth column would appear in the city if he left, the general prepared to march out and deal with the regrouped Vandal army. Before leaving, he subjected his troops to a long speech urging them to be brave and steadfast and so on and so forth. The words Procopius reports probably vaguely line up with whatever Belisarius actually said, but these kinds of speeches are right out of the tradition of Herodotus, and are more about the writer showing off his mastery of Greek and Rhetoric than about accurate reporting. There are a couple of gems in this one, especially “For not by numbers of men, nor by measure of body, but by valor of soul is war to be decided.” But they’re buried in rhetorical muck and there’s a reason I haven’t quoted any of the ones that have appeared in the narrative before now. They tend to go on a bit. Having thus … inspired his men, Belisarius led his army westward to find Gelimer and Tzazon, and get this thing finished. He detached all but 500 cavalrymen, and the bucellarii, again under the command of John the Armenian, to head out and skirmish with whatever force they found in the immediate area. The next day, the general followed with the remaining cavalry and infantry.

The Vandals knew they were coming. Gelimer had sort of fortified his position – Procopius calls his construction a stockade, but hastens to add that it did not rise to the level of fort. He put all his camp followers and baggage inside it, and gathered his fighting men. He made his own inspirational speech, and asked his brother to make one as well, so we have two for the price of one. “It is our boast that in Manliness we surpass our enemy, and that in numbers we are far superior,” said Gelimer. According to Gelimer, or rather, according to Procopius via Gelimer, the Vandal force outnumbered the Romans 10 to 1. That seems impossibly high, and in his biography of Belisarius, historian Ian Hughes suggests 8,000 for the Romans, and 15,000 for the Vandals. Belisarius was still outnumbered, but maybe not suicidally so. Gelimer also tried to put the defeat at Ad Decimum down to bad luck, hoping to erase the memory that he had lost heart and control of his men at the crucial moment.

Another crucial moment was at hand. In the middle of December, 533, at a place called Tricamerum, the Vandals moved out to meet the Roman force, and caught them as they were preparing their midday meal. The two armies arrayed themselves, the Romans a bit haphazardly, on either side of a small brook. John was out in front with the cavalry, federate troops on the right, Belisarius in the center with his small cavalry force and the main body of the infantry, and the Huns off a bit to the rear, whether because they were waiting to see how things turned out, as Procopius asserts, or because Belisarius didn’t trust them, who can say.

For a while the two sides looked at each other over the stream. Then they looked some more. Then they switched things up and observed each other across the water. John finally broke the tension, by charging at the Vandal center. Gelimer had instructed his men to fight at close quarters, with swords only, no spears. They were able to beat back John’s initial charge, but the Armenian reformed and tried again. This charge was also repulsed.

On the third try, John was backed up by Belisarius and the rest of the army, who crashed into the Vandal line just beyond the river. Fighting was fierce and personal, Gelimer’s dictum to use only swords making the fight an affair of sweat, strain, and very personal hatred. In the fighting, Tzazon was killed, within sight of his brother. As it had at Ad Decimum, the loss of a brother took the wind out of Gelimer, and he and his men began to rout. It started in the center, with Gelimer and his men flying back toward the stockade. Again the high proportion of cavalry on the Vandal side seems to have mitigated the slaughter, but the Vandals had lost the day.

Belisarius took a moment to reestablish discipline before he marched on the Vandal camp, but when he came, he brought every one of his 8,000 friends with him. When Gelimer heard this, he abandoned the camp with only his close followers and retainers, abandoning it and its contents to the Romans. The other fighting men also fled, and the Romans took possession of a fortified camp populated only by women and children, and the supplies and treasure that Gelimer had managed to hold on to. The civilians were captured and sold into slavery, the movable goods carted back to Carthage.

Gelimer and the Vandals that found their way to him made their way westward, along the same road they had been traveling when they fled from Ad Decimum. It led to Hippo Regius – the city on the coast that was the capital of Numidia, and the onetime home of Saint Augustine. Belisarius gave a taskforce of 200 men to John to hunt the Vandal king down and capture or kill him. The Roman party traveled for five days, gaining on Gelimer all the while, until fortune intervened. A soldier in John’s party took a pot shot at a bird, perhaps thinking it was getting close to lunch, and struck John in the neck. The hunt for Gelimer was abandoned, as the soldiers cared for their mortally wounded commander. Before he died, John was adamant that no revenge be taken on the soldier who had fired the unlucky shot, because accidents happen. Belisarius was distraught over the loss of his star commander and friend, and actually set up a fund to ensure his grave would be well cared for.

In the meantime, Gelimer made it to Hippo, but did not occupy the city, instead he climbed into the nearby mountains and set up a stronghold there. Procopius calls the place Mount Papua, or Mount Pappus; most likely this was Edough Mountain, just outside of the city, in modern Algeria. Fun fact, the mountain was the last place in North Africa to host a population of lions, and the ruins of the aqueducts that once served Hippo are still visible there today.

The mountain was a formidable obstacle on its own, and it and the town of Medeus at its base were home of one of the few Moorish tribes still loyal to the Vandal king. Also, it was December, and even on the sunny coast of Tunisia, December is winter, even more so in the highlands. Given how long it would take to smoke Gelimer out of his hidey-hole, Belisarius decided he couldn’t afford to be away from Carthage that long, and so he delegated the job to another commander named Pharas, rounded up the Vandals that were still inside Hippo and took them back to the capital.

Pharas was a Herule, and Procopius pays him the dubious complement that he was “energetic, in all things serious, and upright in every way” and that “for [a Herule] to not give himself over to treachery and drunkenness, but to strive after uprightness, was no easy matter and merits abundant praise.” Thanks, I guess?

As the two armies settled into the rhythm of siege (how do you lay siege to a mountain? Seems like a tall order.) Belisarius received another lucky break.

I said earlier that the Vandals didn’t have the degree of Roman cooperation with their regime that the Ostrogoths did, and that’s true, but that doesn’t mean that there were no Roman administrators who gave their loyalty to the Vandals. One of these was a clerk or scribe named Boniface. At the beginning of the war, Gelimer had entrusted a large portion of his treasury to Boniface, and placed both him and it on a ship, with instructions to sail to Spain if things went badly, and take the treasure to the Visigothic King Theudis. After news of the Vandals’ defeat at Tricamerum reached him, Boniface did just that. But the winter weather was against him. He was unable to make headway toward Spain, and instead was blown back, right to Hippo Regius. They attempted to row away, toward some other, friendlier port, but were blown back to the coast again. Boniface interpreted all this as a hint from God – and fair enough, really – and returned to Hippo. He sent a few men to find Belisarius to tell him of the treasure’s existence, and once they received assurances for their own safety, where it was. Belisarius was of course ecstatic to grant amnesty to Boniface, and sent him on his way safely with all his property intact, along with whatever extras he was able to half-inch out of the Vandal treasure.

This treasure was added to the pile that would eventually be shipped back to Constantinople as spoils of war. I have the opportunity here to correct a flub that I made quite a while back. When talking about the Vandals’ sack of Rome in 455, I made a note that the Menorah, the great ritual lamp that had been taken from the temple of Jerusalem, was among the booty that the Vandals took back to Africa with them, and that after that, it disappeared from the history books. That isn’t quite true, it turns out. The Menorah was among the treasures that appeared in the triumphal procession that celebrated the Vandals’ defeat. But someone pointed out to the Emperor that all three of the cities in which the Menorah had resided had been subject to enemy sack, and Justinian ordered it be returned to Jerusalem. Here is where the trail goes cold, there is no record of its arrival in Jerusalem, or of pilgrims going to see it. So apologies for the mix up, hopefully that sets the record straight.

Anyway, life on the mountain was deeply unpleasant for Gelimer and his men. Used to the rich countryside and their commandeered villas, the Vandals found they were unprepared for rough living. Gelimer missed his good food, his bath, his entertainment. When Pharas sent a note calling for him to surrender, Gelimer supposedly sent back a reply in which he refused to do so, but begged Pharas to send him “a loaf of bread, a sponge, and a lyre”. Pharas obliged him, and Gelimer composed a ballad lamenting his bad fortune.

After three months, as winter loosened its grip and the possibility grew that his position might be taken by storm, Gelimer’s defiance wavered. The breaking point came, according to Procopius, when he witnessed two children, brothers, come to blows over a small wheat cake their mother had baked. Acknowledging that surrender was the only way to end his people’s (and his) suffering, he offered to do so, in return for pledges that he would not be harmed. Pharas passed the message on to Belisarius, who agreed readily and sent an escort for the erstwhile Vandal king. When he arrived back and was on his way to meet with the man who had beaten him so thoroughly, Gelimer began laughing uncontrollably, overwhelmed at the fickleness of fate and the completeness of his own reversals of fortune. Belisarius meanwhile asked permission to bring Gelimer to Constantinople alive, and while they were waiting, kept his promise that he would not be harmed, and would be treated with honor. Ultimately, after appearing in the triumph celebrating his defeat, Gelimer was granted vast landholdings in Galatia in central Anatolia, and lived out the rest of his days in very well kept exile.

The Vandals as a people, were a spent force. Procopius notes that there were still some people who called themselves Vandals back in the ancestral homelands in central Europe, but none of North African Vandals even considered trying to return there. They had effectively been made a different nation by the long separation, and even if they had had the means, there was no desire. The European Vandals were on their last legs anyway, and would disappear, absorbed by neighboring tribes, within Procopius’ lifetime. Some African Vandals were sold into slavery as prisoners of war, some migrated to Spain and were scattered across the country, where they integrated with the Arian Visigoths and lost their identity that way. Those that stayed in Africa probably recognized that flaunting their Vandal identity was an invitation to persecution, kept their heads down, converted to Catholicism at least nominally, and faded away. And so we say goodbye to one of the most important barbarian tribes of the last century. Just like that, after a war that lasted no more than four months, they were gone.

Belisarius had not been idle while he waited to see whether he would have to go to the Mountain or vice versa. Under his direction, sub commanders fanned out across North Africa and reasserted Roman control over the towns that had been lost. Some of them weren’t even Vandal towns anymore; the mostly independent fortress city of Septem, now Cueta, on the Straits of Gibraltar, was among those that opened their gates. Sardinia was subdued by the sight of Tzazon’s severed head, and the Balearic islands were also conquered without difficulty. The only snag that Belisarius met was when he attempted to occupy Lilybaeum, on the western tip of Sicily. He found it held by the Ostrogoths in the name of Athalaric and his Regent Mother Amalasuintha. Belisarius sent a letter to the Gothic queen, who had willingly made the eastern ports available to him, advising that she not take action that would turn friendship into hostility. Amalasuintha replied with a touch of sass that that was good advice, but was clearly meant for someone else, since all she was doing was taking possession of a port that Theodoric had lent to his sister on the occasion of her marriage. Now that the sister in question – her aunt Amalafrida was dead, the port had reverted back to its previous owners. That was all. They left the issue there, but the seeds of hostility were being sewn nonetheless. Or maybe Procopius was just foreshadowing, and none of the exchange actually took place. Hard to know. But now I’ve done my duty, and done my own foreshadowing by reporting it.

Around this point, a message arrived from Justinian. The emperor congratulated Belisarius on his great victory, and offered him a choice. He could send his prisoners and plunder to the capital, stay in Africa, and continue to consolidate what he had won; or he could return to Constantinople with his spoils and celebrate there. Belisarius, aware that the ambitious or envious were whispering the traditional accusations in the emperor’s ear (Belisarius was too successful, he’s plotting to make himself an independent king, etc. etc.) prudently chose the latter, to return to Constantinople in triumph.

His preparations to leave though, triggered a revolt by some of the Moorish tribes, who had been thrilled to be rid of the Vandals but were less thrilled to be ruled by the Romans. Belisarius was committed to leaving, and passed command to the man who had delivered Justinian’s message, a general by the name of Solomon. At the same time, administrators and other bureaucrats were arriving from Constantinople to set up a new government and try to make some sense of the mess the Vandals had made of the whole thing. So the conqueror was suddenly replaced by the beancounter, and the reincorporation of Africa into the empire was underway. We’ll hear about how that goes a little bit later on.

Next time though, I want to spend some time with a character who’s popped up a couple times in the last two episodes, and who deserves more thorough treatment. The queen Regent of the Ostrogoths, Amalasuintha, has been working diligently and sometimes desperately to preserve her father’s legacy in Italy, and her story both deserves to be told, and dovetails neatly with the story of Justinian and Belisarius. So we’ll hop across to see what’s been happening in Italy these last seven years or so, and how Theodoric’s kingdom has been holding up.