456 to 513 CE

This episode is brought to you by, you guessed it, Manscaped.com.

Introduction

Having dealt with the Suevi and their rapid expansion and implosion, it’s time to do a little shimmy to the left and return our focus to their adversaries and ultimate destroyers, the Visigoths. The Visigoths have been with us from pretty much the beginning, especially if you accept the simplifying framework that they were descendants of the Tervingi tribe, way back in the mists of pre-Hun history to the north of the Danube. Pre-hun-story. Heh.

We’ve seen them settle

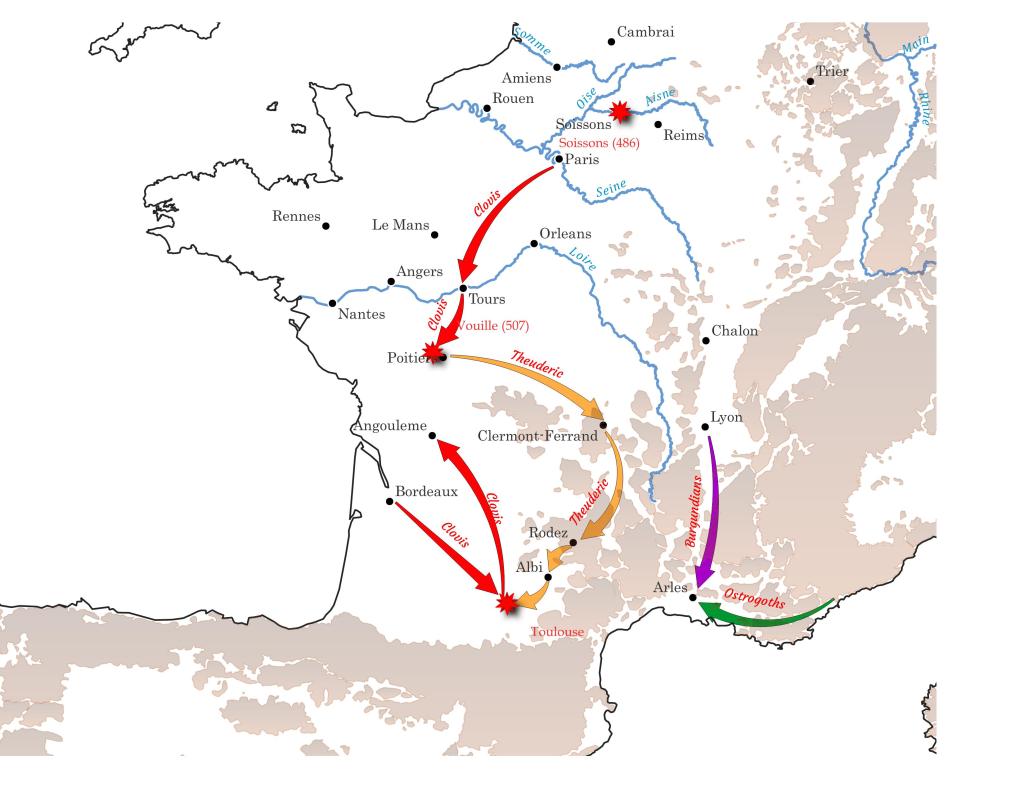

in or occupying chunks of the Balkans, invade Italy, sack Rome, be pressed hard in northern Hispania before finally finding a Roman generalissimo prepared to deal with them, and carving out a federate kingdom in Aquitania, aka southwestern Gaul. They’ve faced off against their eastern cousins at the cataclysmic battle of the Catalaunian fields, and in 475 declare their independence from Rome under their aggressive and expansionist king Euric. By the time Euric died, Visigothic power extended over the Pyrenees into Hispania, and on paper Euric’s son, Alaric II, was set up to be one of the most powerful rulers in the post-Roman reality. Alas, Alaric is best known for dying in the catastrophic defeat of the Visigoth army by the Franks at the battle of Vouillé in 507, and the resulting flight of the Goths out of Gaul.

This episode will be about the lead up to, and beginnings of, the creation of a Visigothic polity south of the Pyrenees. We will perforce take a look at the years after defeat at Vouillé, dark days for the Visigoths, and for Hispania, as peace and stability seem always just out of reach.

Historical Silence

Before starting I want to mention, as I have before, that this is a time and place that is almost entirely unrepresented in direct primary sources, by which I mean sources from Hispania at or near the time of the events described. There is only one chronicle that is contemporary, the Consularia Caesaraugustana, and it is a marginal one. It is an annale, much like Hydatius’, a list of years with entries for the consuls that served in it, and a note or two on important happenings. To add to the fun, the Consularia does not survive in manuscript form in and of itself. It is not, like Priscus’ account of the Huns, so many episodes ago, survives in quotations and references in other learned works. No, the Consularia Caesaraugustana survives as notes written or copied into the margins of a copy of the Chronicle of John of Biclaro. So I am not lying or being judgemental when I say that this is a marginal source.

The work covers the years between 450 and 568, so it neatly bridges the gap between Roman and not-Roman periods. However, it is pretty tightly focused on its namesake city, Caesaraugusta, known to us today as Zaragoza, (which, if you mumble and say Caesaraugusta quickly, you can see how we got to the name Zaragoza). That tight focus means that we have only a few mentions of the kind of thing we’re interested in, and we have to use the Consularia in tandem with later writers or writers from outside Hispania, like Isidore of Seville or Jordanes, to understand its often cryptic, sometimes contradictory entries. I’ll flag these types of moments as they come up in the narrative, and hello, here comes the narrative once again, backing up just a bit. (BEEP BEEP BEEP)

The Kingdom of Toulouse

We talked last time about the Visigoths’ defeat of the Suevi and the execution of their king Rechiar in 456, which forced the Suevi back to their stronghold in Galicia and plunged them into decades of civil war. That effort was initiated, and possibly led, by King Theodoric II. Reading between the lines, we can guess that Visigothic elites who accompanied him on campaigns took the opportunity to grab some territory for themselves. Who knows what form this may have taken? Maybe local elites simply recognized that the Goths’ demands for taxation were actually lower than imperial demands had been, and submitted willingly? Maybe a warband would take on garrison duty for a town or city, and the city fathers would find themselves under the thumb of their commander, maybe vacant land could be simply occupied and the locals put back to work on it, or maybe villas were occupied by simple brigand force, their owners sent flying headlong out the door with a boot-shaped print on their backside and a warning not to come back ringing in their ears. It was probably all of these, each little drama playing out all across the countryside.

Euric

In 466, Theodoric was murdered by his brother Euric, and whatever other changes Euric may have brought to the administration of the kingdom of Toulouse, there is no evidence that he did anything to stop the occupation of Hispania. On the other hand, there’s little indication that much effort was put toward exercising much central control over the provinces, and Gothic lords probably enjoyed a fair degree of autonomy. Euric was the most expansionist of Gothic kings, fighting in the north to extend his territory to the Loire River. In 475 he declared himself independent of the Roman empire, he did not rule as a legate, even fictively. He was the first Germanic king to do so, and Julius Nepos was forced to accept and recognize this declaration, in return for Provence. Most of the Roman nobility of Hispania accepted and recognized Euric as well, and after 476, even the administrators in Tarraconensis, who had held on to the empire the longest, gave up, and acknowledged Euric as overlord. Probably, by about 480, Euric’s on-paper dominion of the peninsula was complete.

That didn’t mean though, that they were immediately crushed under a hairy Gothic boot.

The idea given by maps of complete territorial control is a false one, and while most of Hispania may have acknowledged some kind of obligation to the Gothic king, the realities of communication made real control difficult.

That could explain some of the seemingly contradictory entries in the Consularia Caesaraugustana. Notably, in 493, which is, um, after 480, the chronicle notes that “the Goths entered Spain”. Hm. Again, four years later, in 497, another entry, “the Goths acquired settlements in Spain.” So what does that mean then?

Local Trouble

It could be that the entry refers to some kind of transition, where the region around Zaragoza had been paying taxes to Euric but now Goths were arriving to take direct possession? We can’t ever really be sure of course, but that’s one explanation, and it is suggestive of the very local reality of all of these grand political changes. For large chunks of the empire, after 476, the only thing that really changed was the address you sent your tax return to. And actually, overall, the tax bills were lower, which certainly helped both Gallo- and Hispano-Roman elites make peace with new realities.

That localism is further emphasized by a couple of other entries in the Consularia. In 496 we are told that “Burdunellus became a tyrant in Spain”, before being overthrown by his own men and sent to Toulouse to be executed horribly. Later in 506, a man named Peter made himself a “tyrant” in Dertosa, and again was quickly deposed and executed, and his head sent to Zaragoza. Peter’s treason seems to have been of smaller magnitude than Burdunellus’. Once again, we are stymied by the laconic chronicler, and can only guess at what might be going on here. Best guess is that both of these men attempted to declare themselves in opposition to Visigoth overlordship, maybe they were acclaimed as emperors by their men. But such rebellions challenging Visigothic hegemony are suggestive, as I’ve said, that that hegemony was not complete.

Religion

Religion also made it difficult for the Goths to get a firm grip. When Clovis I converted to Catholicism, in 500 or so, he gained access to the most advanced communications, administration, and propaganda network that existed in the absence of imperial control: the Church. The network of priests and bishops had been corresponding and deepening their connection to local society for three hundred years in most places, given an enormous boost of course by Constantine and his successors. As the civil administration became ever more parochial and less connected to Rome, the clerical network remained strong, a pool of connected, literate, well educated men who still saw themselves as part of a greater, pan-European unit.

The Arian church had a network as well, of course, but since Arianism, especially by now, had mostly grown among the migratory Germanic tribes, it had not been able to develop the kind of infrastructure that was available to the Catholic Church. Its position as the opposition to the established Roman Church also meant that leaders might encounter resistance based on religious grounds where otherwise locals might be open to a change in administration. As we saw, even in the relative calm and harmony of Theodoric’s Italy, religious differences kept the Germanic soldiers and rulers and the Roman civilians from forming an integrated, shared identity.

Gothic Solidarity

Speaking of Theodoric, strong connections were formed between the Visigoths and the Ostrogoths after the latter’s takeover of the Italian territories. Remember that the distinction between Visi and Ostro is mostly a modern construct, so we can keep our history straight. Most contemporaries referred to both peoples as simply Goths. Intermarriage between the two was common, and the connection would be useful for both of them, as we’ve already seen.

Visigothic military power had helped Theodoric in his war against Odoacer, and in 494 Theodoric’s daughter Ostrogotho was married to the Visigothic king Alaric II. Alaric had become king on the death of his father Euric in 484, and the alliance this marriage cemented would prove to be essential to the Visigoths in the very near future.

The Aftermath of the Battle of Vouillé

Alaric is one of those unfortunate figures of history who is best known for his greatest failure. God forbid this podcast should become best known for its worst episode… which one is that, do you think? Send me an email…

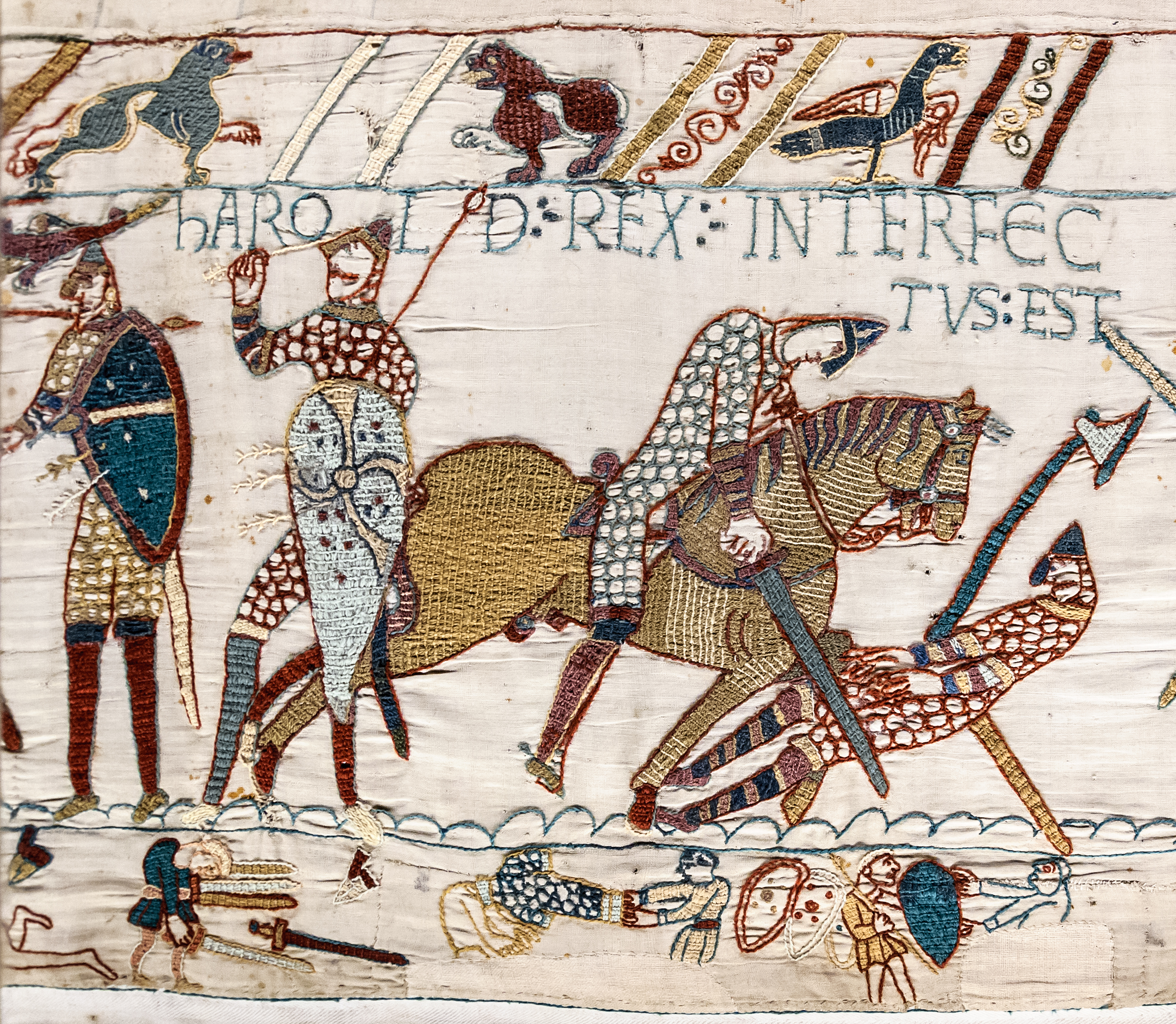

Alaric’s great failure was his defeat and death at the battle of Vouillé, fought against the Franks in 507. We talked about it in episode 35, Clovis a-Conquering. The battle led to the rapid collapse of Visigothic power in Gaul, the capture of the capital at Toulouse and the royal treasury, and the withdrawal of the ruling Balth dynasty to Narbonne on the Mediterranean coast. Only the intervention of Theodoric’s army, under the command of a general named Ibba, prevented the loss of those coastal territories. Just as we saw in 456, when the battle of Orbigo triggered the collapse of the Suevi, a single engagement threatened the whole Visigothic kingdom.

Why did it though?

Why are these individual clashes so often decisive? Now it’s a common understanding that one might lose a battle but could still win a war, so why was it different then?

The Mechanics of Defeat

There are a few reasons, some specific to the Visigothic case, and some more general principles.

To begin with the specific and immediate first. We can’t be sure just how many Visigoths had crossed over into Hispania to grab territory and glory, but we can be pretty sure that in these early stages, most of them were fighting men, and depending on how large units were – probably not very – a relatively large proportion of them would have been commanders. So it may have been that when Clovis arrived, the Alaric II did not have the full military resources of the Gothic kingdom available to him to meet the threat. The slim pickings may have contributed to the defeat at Vouillé, and that plays into a more general discussion of the culture that helped make individual battles so potentially catastrophic.

The cultural mores around kingship and military practice that seem to have been common among most of the Germanic peoples were practically purpose built to ensure that one open battle could be decisive. The legitimacy of the king depended on his ability to lead and enrich his most important men, so a sense of confidence and air of success was absolutely essential. In return, the leading fighting men of the kingdom pledged their absolute loyalty, and they weren’t kidding about that. It was expected that when a king or great lord died in battle, his closest retainers would fight to avenge him, or, failing that, would stand and fight to the last man rather than surrender. The chronicles are full of large and small conflicts that end with the band of merry warriors going cheerfully to their deaths, covered in honor and glory, for they did not abandon their lord in his time of need.

All very romantic, but it meant that in the case of a large battle, a kingdom might have a sizable portion of its military elites scraped off and killed in one go, and that made mounting a counter-offensive difficult. Ironically, the absence of so many lords, away in Hispania, may have preserved a large enough segment of the Visigothic elite that the kingdom could carry on, even with the king dead and Aquitaine lost.

Treasure

One quick digression, there is an interesting second component of royal legitimacy that came to my attention while doing the reading for this episode. It has to do with treasure. You may remember, if you are currently binging the podcast, or have a truly impressive memory, that I made a note of the capture of the Royal treasure at Toulouse by the Franks. Now, obviously it makes sense to take control of the defeated kingdom’s money, but it turns out it’s more than that.

Besides the rather mercenary relationship between king and elites, the royal dynasty’s legitimacy was based on an understanding of shared history. That shared history is recorded and personified by the royal treasure. Aside from the material wealth it represented, it usually contained objects that recalled past events and achievements. This has been a thing going back to Mesopotamia, where a victorious army would often take a defeated city’s god back to their own temple. In a less mystical but still psychologically significant way, the royal treasure of the Visigoths or Vandals were reminders of their past victories and glories. The obvious example that I’ve talked about before is the Menorah. If you remember, it was part of the treasures of Rome, and reminded the Romans of their victories over the rebellious Jews. It was captured by Gaiseric in 455 and became a part of the Vandal treasure, reminding them of their victory over and sack of Rome. It was then taken to Constantinople by Belisarius. Each time it accrued a new layer of significance to a new victorious group.

Though we don’t have specifics, we are told that the Visigothic treasure contained pieces taken from Jerusalem during the revolt of 69 CE as well, which had taken on even more significance since the conversion of both Goth and Roman to Christianity. It would make sense for that to have been the case, Alaric I would have gathered as many tokens of his victory as he could carry, to keep with him as a record of his and his people’s triumphs. To have the royal treasury stolen was to lose part of that collective memory, and so the sack of Toulouse by the Franks was a psychological blow beyond its military importance.

In spite of these blows, the Balt dynasty, which had been ruling the Visigoths since the desperate days of Alaric I, remained the royal house of the Visigoths, and a new Balt was elected by the surviving Visigothic nobles.

Gesalec

His name was Gesalec, and he was an illegitimate son of Alaric II. We know nothing at all about his mother, other than she is described by Isidore of Seville as a “concubine”, and as far as Isidore’s concerned, that’s all anyone needed to know to predict how this was all going to play out.

Alaric had a legitimate son, Amalaric, whose mother was Ostrogotho, which made him Theodoric the Great’s grandson. But primogeniture was not at all a given yet, the most suitable candidate from the royal house was selected to succeed the king, and Amalaric was only five in 507. He was taken south into Hispania, to safety away from the front lines.

The nobility had gathered in Narbonne to elect Gesalec, on the southeast coast of Gaul. Narbonne was an important port, and probably the largest city in Septimania. And I have to be honest with you, I just dropped the name of the region entirely so that I could launch into another digression.

Septimania

Septimania was the coastal strip in southern Gaul between the mouth of the Rhône and the Pyrenees. It would be part of the Visigothic domains as long as they existed; a little cowlick of territory off the Spanish head.

Now here’s the digression part. Septimania, you may be thinking, sounds like it has something to do with the letter seven. Actually you probably weren’t thinking that, you were probably thinking, get on with it, loser, but it’s my show, so I’m going to pretend it was the first thing. And indeed, gentle and erudite listeners, there are two possible origins for the name, and they both have to do with the lucky number seven.

First, it may come from the Roman name for the modern city of Béziers: Colonia Julia Septimanorum Baeterrae, which in turn is derived from the seventh legion, many of whose veterans were settled there. I don’t want to get dragged into nesting digressions, but can I just say that the Romans were absolute garbage at naming cities, they either have seven words each, or they’re all called some version of Caesarea, drives me up a wall trying to figure out where anything was.

Anyway, the second possibility for the origin of Septimania is after the seven civitates, cities, duh, that constituted the region. These are now called Béziers, Elne, Agde, Narbonne, Lodève, Maguelonne, and Nîmes. Look, I know it’s not really germane, but I put in all the time learning to pronounce those, so they were going into the episode come hell or high water. And if you go to the transcript and web page for this episode on darkagespod.com, you will see that I also took the time to put in all the accents and circumflexes, and stuff, so there. Feels like I’m yelling at you, I’m not, just, you know it was late when I was writing this and I was a little bit wired.

Where on earth was I?

Really, Gesalec

Right. Gesalec was probably in his late twenties when he was elected king, and we have absolutely nothing contemporary to tell us anything about him. Instead we are pretty much stuck with Isidore of Seville, who was writing over 100 years after the fact, and whose judgment is not favorable. “He had neither bravery nor luck” according to the good bishop of Seville, and most historians writing since then have pretty much followed that line, but let’s just wait and see what we think.

Gesalec’s name by the way, means “dancing with spears” which I think qualifies as the most metal name we’ve yet encountered, so points for that.

The intervention of the ostrogoths had ensured that Septimania remained Visigothic territory, but the Ostrogoths had not actually fought the Franks, they had fought the Burgundians.

Alliance with the Franks had emboldened the Burgundians and their king Gundabad. This was the same Gundabad who had been master of soldiers of Rome, but who abandoned that position when the kingship of the Burgundians became available. After the defeat at Vouillé Gundabad pushed down the Rhone and laid siege to Arles. The Ostrogoths, under their general Ibba, dished out heavy punishment and pushed the Burgundians away from Arles and Avignon and took possession of Provence.

We’re not sure when exactly it happened, as Isidore does not give a date, but at some point around this time the Burgundians invaded Septimania and plundered Narbonne. Whether they decided they couldn’t hold it and withdrew to Arles, or if this was a detachment from the main invasion force, or an entirely different army in a different year, we can’t say for sure. But however it went, Gesalec offered no resistance, and fled Narbonne to Barcelona. Okay, so not much there to contradict Isidore’s assessment of cowardice, but we have very little context. If the sack of Narbonne did come hard on the heels of Vouillé, then Gesalec’s military resources would have been scant indeed, and a tactical retreat may have been the only option available to him. That did not square with the Germanic ideal of fighting to the death – and retreat, regardless of circumstances, brought shame, and so Gesalec may have been doomed to ignominity from the beginning.

A Gothic Coup

At first, Gesalec enjoyed the support of Theodoric the Great, though what form that support took is hard to say. It must have been significant, and it apparently gave him considerable leverage over the Visigothic elites, because in 511, he deposed Gesalec in favor of the passed-over Amalaric. That wouldn’t have been possible without the collusion of the Nobility, and dissatisfaction with their ruler must have played a part in the coup, along with Theodoric’s influence.

The picture that emerges for me, sketchy though it is, is of a king who was dealt a bad hand, and who got no breaks whatsoever as events unfolded. I wish there was more detail, because this is the kind of political maneuvering that makes for a really compelling narrative, if only we knew how it went down. But Isidore is resolute in his conviction that brevity is a virtue of chroniclers, and as E.A. Thompson noted, he “could hardly have told us less, except by writing nothing at all”.

The Visigoths acclaimed Amalaric, the legitimate son of Alaric II, as king; and since he was still a minor, at only nine years old, Theodoric the Great declared himself regent of the Visigothic kingdom. How nice of him.

After the coup, Gesalec fled to Carthage, seeking refuge with King Thrasamund of the Vandals. We have a letter written by Cassiodorus on behalf of Theodoric that expresses the Ostrogoth’s feelings on the matter: “Having given you our sister, that singular ornament of the Amal race, in marriage, in order to knit the bonds of friendship between us, we are amazed that you should have given protection and support to our enemy Gesalec. If it was out of mere pity and as an outcast that you received him into your realm, you ought to have kept him there; whereas you have sent him forth furnished with large supplies of money to disturb the peace of our Gaulish Provinces. This is not the conduct of a friend, much less of a relative. We are sure that you cannot have taken counsel in this matter with your wife, who would neither have liked to see her brother injured, nor the fair fame of her husband tarnished by such doubtful intrigues. We send you A and B as our ambassadors, who will speak to you further on this matter.”

I’ve covered this letter a bit before in an earlier episode.

When Thrasamund began clearing his throat and making ostentatious glances at the door, Gesalec returned to Aquitaine, hoping to recruit men for a comeback. That’s interesting in itself, since it suggests that the Frankish hold on Aquitaine wasn’t particularly strong, and that there were still plenty of Visigoths settled in Aquitaine, some of them fighting men. It’s also interesting to me because in that excerpt I just read, Theodoric refers to his Gaulish provinces. That may refer to Provence, which was under direct Ostrogoth control, or it may refer to Septimania, and THeodoric was letting the mask slip just a bit.

Gesalec did manage to put together some kind of army, and in 513 attempted to march on Barcelona, but was intercepted by an Ostrogothic army commanded by general Ibba, and was defeated. Again Gesalec fled the field. He was probably heading to try his luck with the Burgundians, but he was caught, probably near Avignon, and executed. Whether his captors were Burgundians or Ostrogoths, no one says.

Gesalec was around 33 years old when he died, and had been king of the Visigoths for four hard-pressed years.

The Ostrogothic Interlude

The decade following the overthrow of Gesalec is called the Ostrogothic interlude by some historians. During that time Hispania was governed by a regency government directed by Theodoric the Great. We will talk more about how that worked, and how it came apart, and what happened next, in our next episode.

In the meantime, thank you for listening, and thank you for your very generous contributions on ko-fee.com/darkagespod.

That’s all for today, except to mention one more time that you can get 20% off and free shipping on Manscaped.com if you use the promo code DARKAGES at checkout.

Until next time, take care.