Today is a day for getting a move on, putting on the afterburners, and getting the lead out. I left you all on a down note last time, as Gesalec was murdered after a failed attempt to undo his deposition by Theodoric the Great. Today is about the next fifty years or so of high politics in the Visigothic kingdom, and by high politics I mostly mean war. Is anyone surprised? I mean really.

We will start with the regency period of Theodoric on behalf of his grandson, and how that all worked in practice. Once that odd period, the ostrogothic interlude, was over, the Visigoths suddenly found themselves running low on royals, and instability was the result. Instability, as it often does, attracted the attention of outside powers, in this case Franks and a little later on, Romans. Not to spoil anything, but when we end today the long arm of Justinain’s restorationist ambitions will have reached all the way across the sea to land lightly on the sunny beaches of Hispania.

There will be war, there will be chaos, and I’m very sorry to say, there will be names. Some familiar names – Theodoric, Justinian, and a surprise guest I won’t mention yet, and there will be a new crop of Gothic names. The good news there is that, just like the names of the Suevic kings I talked about a couple episodes back, I doubt many of them will come up ever again. Harsh, but true, so you don’t have to worry about seeing them on the test. A shortish episode, ultimately, but a packed one. So if you have taken a deep breath, we can take the plunge.

Amalaric

When we left off last time, Gesalec, the oldest son of the unfortunate Alaric II, had made a last ditch effort to make a comeback, looking for support among the remaining Goths of Southern Gaul, and coming up short.. Nominally, Theodoric’s grandson Amalaric was king, but while he was a minor, Theodoric set himself up as regent, and so directly or indirectly ruled a swathe of territory that stretched from Portugal to Croatia. Now hang on just a sec, Goths of southern Gaul? I thought they were all turfed out by the Franks after 507?

Yes and no, whenever I say “so and so were driven out of here and there”, it helps to keep in your mind that what I usually mean is that the elites of the so and so’s have been forced out. Just as we’ve talked about in regard to existing Roman populations, the effort involved in actual wholesale replacement of one group with another was far beyond the reach of any barbarian king, plus it would be counter productive, you need someone to manage the harvests and such, otherwise who is going to pay your taxes? So the king and his followers were creamed off and forced over the mountains, but there were still plenty of Goths in Aquitaine and the Auvergne, and it actually took the Franks a decade or two to really make their conquest of the region stick permanently.

This is what history is like, isn’t it? We have been presented with big blocks of color moving around on maps, and it’s very easy to forget that those blocks are all made of thousands of individual pieces that all make their own choices, whether to stay together with the rest of the red pieces as they move, or to stay put and try to stay red while the blues move in, or to change to blue and just hope for a peaceful life.

I babble. Let’s get back to Theodoric the Great, the Ostrogoth who had pushed out the illegitimate Gesalec and now ruled on behalf of his grandson, the young Amalaric.

Regency

It’s almost impossible to know the exact nature of Theodoric’s regency in Hispania, and even more difficult to know how the Visigoths felt about it. All the evidence we have is circumstantial. It’s straw in the wind. To begin with are two ecumenical councils, one in Tarragona in 515 and one in Gerona in 516, which are dated to the fourth and fifth years of Theodoric’s reign, which would suggest a) that Theodoric was ruling directly, not as a regent, and b) that he had begun doing so in 511, immediately upon the deposition of Gesalec. Tribute was certainly being sent to Ravenna as well. Historian Herwig Wolfram is unequivocal about the situation, writing that “Theodoric did not merely want to save the Visigothic Kingdom, he wanted to gain control over it for himself.”

Set against this, there’s little evidence for an Ostrogothic occupation of Hispania or Septimania, and Theodoric’s rule seems to have been fairly lightly applied through appointed governors who worked mostly with local military powers. There were Ostrogothic military forces in Hispania but never very many. We have the presence of a governor or viceroy by the name of Theudis, who had been appointed by Theodoric, but who demonstrated a streak of independence. For example, at one point he refused a summons from Theodoric to come to Ravenna, and Theodoric felt that forcing the issue would lead to rebellion, or Frankish invasion, and so let the matter drop. Remember Theudis, we’ll come back to him shortly.

By 522, Amalaric was twenty years old, and ready to take direct control of his territories. Tribute payments to Italy apparently ceased no later than 523. If Theodoric had ever considered Hispania as part of a re-invigorated Empire, he wasn’t prepared to usurp the rights of his grandson to make it happen. Relations between the two Gothic halves remained cordial, and given the continued threat of Frankish and Burgundian aggression, that was good for both. According to Isidore, Theodoric “gave the kingdom” to Amalaric prior to his death. He doesn’t give a date, but the Second Council of Toledo, in 527, convened in the fifth year of Amalaric’s reign, so 522 is the logical conclusion, and fits with the other evidence. Such is the documentary detective work that historians often have to do in their pursuit of light, truth, and a coherent chronology. Theodoric still exercised influence over events in Hispania, but after his death in 526, none of his successors had the wherewithal to continue to do so, and Amalaric was completely independent.

Sole rule

Pretty much nothing is recorded of Amalaric’s activities as king. Amalaric married a Frankish princess named Chrotilda, who, being a Frank, was a Catholic christian. She was unwilling to convert to the Arian faith, and for this reason, Amalaric began to abuse her. In distress, she wrote to her brother, who happened to be king Childebert. Childebert attacked Septimania and defeated Amalaric at Narbonne, and in a spooky reiteration of Gesalec’s fate, Amalaric fled to Barcelona, where he was caught and murdered while on his way to the church in search of refuge.

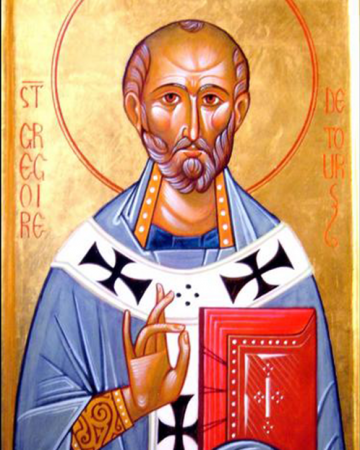

That story comes mainly from Gregory of Tours, who is absolutely committed to promoting the cause of Catholic Christianity, and so may be exaggerating the spousal abuse story. (He reports that Chrotilda sent her brother a towel soaked in her own blood as evidence of the severity of Amalaric’s crime.) The equally catholic Isidore of Seville doesn’t mention Amalaric’s wife at all. The relevant entry in his chronicle reads: “[He] ruled for five years. But when he had been overcome in battle at Narbonne by Chilibert of the Franks, he fled in fear to Barcelona, and having been made contemptible in the sight of all, he was executed by his army that had come from Narbonne and perished in the forum.” Again, we’re back to the shame of cowardice. This, by the way, is the only mention that Amalaric gets in Isidore’s chronicle, beyond what I’ve already told you.

Regardless of Amalaric’s marital problems, we can be reasonably sure that there was ongoing trouble with the Franks to the north. Maybe Amalaric was attempting to ease these tensions with a marriage to the king’s sister, but it doesn’t seem to have worked. Under Theodoric’s protection, the Visigoths were able to push their borders back a bit into Gaul, maybe even briefly as far as Toulouse, but in the long run that just encouraged raiding and instability along the border. Maybe it was one of these raids that led to Amalaric’s death.

Childebert, by the way, was the third of Clovis’ four sons, and had made himself king of Paris, and participated fully in the early Merovingian’s games of fratricide and plotting, which I will save for another time, though I have already told you of the conspiracy he and two of his brothers undertook to murder their nephews upon the death of their father, back in episode 37, the Magical History Tour.

That’s for another time though. Whether Amalaric was killed by raiding Franks or by his own men, disgusted at his cowardice, his death marked the end of the dynasty that claimed descent back to Alaric I. He was around 29 years old, and depending on your reckoning, had been king of the Visigoths for five or nine years.

What to do now?

Theudis

The tradition was that the most competent and promising member of the ruling dynasty would be chosen as king, and now there was no ruling dynasty left to choose from. We’ve seen this happen before in the kingdom of the Ostrogoths, when Theodahad, the last of the Amals, was overthrown and killed. Or will be overthrown and killed, since in our current timeline, that won’t happen for another five years or so.

In the absence of a Balt, the Visigothic nobility looked around and wondered.

It would have to be someone with both military and administrative experience; someone they could trust; someone who would be impartial and could settle disputes among the noble families without being accused of favoritism. And their eyes fell on Theudis, the governor/viceroy or whatever that Theodoric had sent at the beginning of Amalaric’s reign. He was married to a woman from an old Hispano-Roman family, so he could maybe bridge the divide between the two societies. He had been a successful commander both in the army of Theodoric, and leading Visigothic troops against the Franks, but had no army of his own that they needed to worry about. Apparently the core of his military following were actually slaves that belonged to his wife. Like them, he was an Arian Christian, and of high birth, but that nobility was mostly on the Italian side of the ledger, which set him apart from Visigothic politics and family feuding. The more they thought about it, the better the choice seemed, and so Theudis was elected king. Herwig Wolfram adds the possibility that Ostrogothic nobles that had come with Theudis upon his appointment may have helped swing the thing in his favor, though given everything I just went through, I’m not sure that’s necessary to explain his selection.

African Worries

Taking stock, Theudis can’t have been overly optimistic. Though we don’t have a blow-by-blow listing, it’s clear that the Franks had been raiding into Visigoth territory more or less continuously since Vouille. It’s hard to set up housekeeping in a new place when the neighbors keep breaking the windows. The early years also brought with them increased interest from Constantinople. Theudis received word in 533, just two years after his election, that the Vandals had been defeated at the battle of Ad Decimum, and that Carthage had fallen to Belisarius. He received the news before Vandal ambassadors had arrived to ask for his help, and he rather cruelly strung them along, declining an alliance and advising them to the sea coast, for “from there you will learn of affairs at home with certainty.” The ambassadors did return to Carthage, and were duly captured by the Byzantines.

The fall of Vandal Africa was a worry to Theudis, since trade connections between Africa and Hispania were close, and each could be seen as a gateway to the other. But every problem is also an opportunity, and Theudis took the Vandal’s misfortune as a chance to grab the prosperous and strategically important port at Ceuta, on the African side of the Strait of Gibraltar. That kind of initiative probably helped his standing among the Gothic nobility.

Theudis also got pretty good press from the Catholic chroniclers, since even though he was personally Arian, he made no moves against the local Catholic community. He also approved and supported three ecclesiastical councils in his provinces, one in 540 and two in 546, which was noted approvingly by Isidore of Seville. Maybe his marriage to a wealthy Roman woman helped in this regard.

Frankish Defeat

In 541 a large Frankish army penetrated deep into Tarraconensis and laid siege to Zaragoza. The army was apparently a joint command of two Merovingian kings, Childebert, who we’ve already met, and his younger brother Chlothar, the king of Soissons. Chlothar was the most driven of Clovis’ sons, constantly fighting to expand his territories. His brothers more or less went along with his schemes, mainly to avoid becoming his targets, and this attack into Hispania was probably such a campaign. The outcome is unclear, as there are two widely divergent stories. Isidore of Seville reports that a Visigothic general named Theodegisel attacked the Franks as they besieged Zaragoza. He took bribes from some and allowed them to escape, the rest he fought and massacred to the last man. On the other hand, Gregory of Tours reports that the Franks conquered much Spanish territory and returned laden with treasure. Gregory, we know, is generally on the Frankish side, but actually the two stories aren’t mutually exclusive. The franks seem to have been successful up until they reached Zaragoza, and the men who did return probably did return a little richer, so it may be a case of Gregory simply leaving out a few details in the name of spin.

If we accept Isidore’s account, then here is the first instance of the Visigoths successfully fighting off Frankish aggression since Vouille.

Image from the Spurlock Museum at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. https://www.spurlock.illinois.edu/collections/search-collection/details.php?a=1924.02.0068

Theudis is the first Visigothic king that has had any kind of aura of success since Theodoric II, and in 546 he ticked off another box on the good king list by issuing a Code of Laws. I’m planning an episode to go into the state of Law in the Post Roman age in a little bit, and I’ll talk more about Theudis’ code then, but just nota-bene, Theudis is right there with Theodoric in trying to bring some order to the post-Roman chaos.

Theudis’ end will sound familiar, if you think back along the line of Visigothic kings. Let’s hear it from Isidore: “he was wounded by someone in the palace who had feigned the appearance of a demented person in order to deceive the king. He feigned insanity through skill, and stabbed the king, who after being laid low by this wound fell, and breathed out his soul by the force of the sword.” Murder in the palace. If we take a census of every Visigothic king, going back to Alaric I, we will find that out of the eleven kings we’ve talked about, six have been murdered, two died in battle. Only Alaric I, Wallia, and Euric have managed to die in bed. And now Theudis, proving that not being of the Balt dynasty was no protection. The actual reasons for the assassination are unrecorded, and we’re forced to speculate.

Most likely is probably a blood feud, which is neat, since it will nest very comfortably alongside that discussion of Law that I’ve got simmering. We’ve seen kings laid low by blood feuds before, notably Ataulf, who was murdered by Sigeric way back when, who was in turn taken out by Wallia. Theudis’ connections to the Ostrogothic elites only widened the pool of potential assassins. Family honor was a deadly serious concept among the Goths, and a man might pay with his life for a relative’s transgressions. Best not to speculate too far about what specific act might have motivated Theudis’ killer – he was a king, it’s impossible to be a king without making enemies.

If it was an honor killing, though, Theudis broke the cycle of vengeance with his dying breath. According to Isidore, as he was pouring his life out onto the floor, Theudis called that his assailant should not be killed, for he had already punished himself, by depriving himself of a leader. Which somehow manages to be both generous and haughty at the same time. Theudis was in his late sixties when he died, and had been a relatively successful king of the Visigoths for seventeen years.

Civil War

So now a new generation of Visigoths faced the same problem they’d faced when Amalaric had died, an empty throne and no established dynasty from which to pick a successor. If Theudis had any children, they aren’t mentioned and must have been unacceptable in some way. While their dynasty had failed, there was at least still a dynasty available, though it was an imported one. The general who had driven the Franks away from Zaragoza, Theudigisel, had powerful relations, he was the son of Theodahad, king of the Ostrogoths and murderer of Amalasuintha, and that made Theudigisel a grandnephew of Theodoric the Great. A man with a noble pedigree and proven success in battle? The election of Theudigisel must have been a cakewalk. And we are already halfway through all the information I have about his rule.

The Visigoths came to regret their choice almost immediately. Isidore accuses Theudigisel of serial adultery with the wives of his great men, by “public prostitution” whatever that means. Unwilling to tolerate such goings-on, and worried that the king might become murderous if he was called out on his behavior, the nobility threw a banquet, where the wayward king was “extinguished” by stabbing. Theudigisel was probably 48 or 49 when he was killed in 548, and had been king for about 19 months. I’m personally happy for him to have had such a short run, since Theudigisel is a vicious name to have to pronounce. I’ve found the alternative Teudiselo in a couple Spanish sources, but I’m not sure that’s much better.

The next few years were a confused muddle, as something like an open civil war broke out among the Gothic nobility. The traditional dynasties were spent, so the various families fought to make themselves the new tradition. By the way, if you want to visualize the kinds of fighting men taking part in all this violence and rancor, you could do worse than to re-watch The Lord of the Rings, which is actually always a good idea. At the risk of summoning scorn from the legions of people on the internet even nerdier than me, The aesthetics of the Riders of Rohan are at least partly based on Gothic designs, and the Goths remained largely a cavalry force.

Agila and Athanagild

The primary contenders to emerge from these internal disputes were two; Agila and Athanagild.

Agila apparently came to prominence first, if we follow Isidore’s chronology. There are three key events in the struggle between these two leaders: a rebellion in Cordoba against Agila, a second rebellion headed by Athangild against Agila, and subsequently, a call for help to Justinian that led to the Byzantines occupying the southern coast of hispania for the next hundred years or so. In Isidore’s version, it was Athanagild that called for imperial support in overthrowing Agila, but the timeline is confused and we can’t be sure the order these things take place.

Historian Roger Collins suggests that Agila did indeed declare himself king of the Visigoths in 548 or 549, then had to fight to make it stick. The so-called uprising in Cordoba may have been more of a battle in a civil war than a rebellion against an established monarch. Likewise the following rebellion of Athanagild, less a rebellion, more of a refusal to recognize a grab for power. Two powerful nobles and their followers in a simple contest of wills to force the other into submission. These two strongmen apparently found themselves more or less equally matched, and looked to outside help for an advantage.

Enter the Byzantines

According to Isidore, it was Athanagild who reached out to Justinian. In every other intervention we’ve seen, Justinian’s casus belli has been to correct an unjust or unlawful usurpation of a sitting ruler. We saw it in both Africa and Italy, so It would be a bit against type for Justinian to step in in favor of a usurper.

For once, Jordanes may be the more reliable source. At the very tail end of his History of the Goths, almost as an aside, he notes that “Agila holds the kingdom to the present day. [and that] Athanagild has rebelled against him and is even now provoking the might of the Roman Empire.”

It seems much more likely that, contra Isidore, it was Agila that called for help against Athanagild. Jordanes by this point is pretty much writing about current events, as evidenced by the present tense. And, by the way, guess who Justinian tapped to command this expedition to sunny Spain? Nope, not Belisarius. Count Liberius, the Liberius who had served both Odoacer and Theodoric in Italy and Gaul, then slid smoothly into imperial service when it became clear that war was coming to Italy on Belisarius’ ships. Now well into his eighties, we find Liberius leading a small contingent of 2,000 men to intervene in the Visigothic troubles.

It’s kind of a delicious irony, that what happened in Hispania ended up as an inversion of what happened famously in Britain in the previous century. There, the remaining Romano-British sought help from the Saxons to keep themselves safe from more local strife, and the barbarians ended up ruling the island. In Hispania, the barbarian kings sought imperial help in ending their internal strife, and the imperials wound up staying and setting up shop. Because that is what happened. Agila lost a battle and retreated, though it is not clear that Byzantine troops were directly involved in the fighting. Agila’s supporters, fearing that continued conflict would only lead to more destruction and Byzantine domination, killed him and recognized Athanagild as their king. I guess you can’t really be called a supporter anymore once you’ve done that, but whatever.

If the goal of the murder was to prevent Byzantine occupation and domination, then it was a wasted effort. In spite of the efforts of Athanagild to get them to leave, the Byzantine troops stayed right where they were, and set up garrisons. Those Byzantines, once they show up, getting rid of them is going to be a struggle, just like buckthorn, for my fellow midwesterners.

Monasteries in the Eastern Tradition came with the Byzantine occupiers.

Imperial sovereignty stretched over a stretch of southern Hispania, more or less consistent with the province of Baetica, which was named by imperial administrators Provincia Spaniae – finally dropping the H. Over the years this would expand and contract, as stronger and weaker Visigothic kings sought to win back what had been given away. Low level conflict along this border would ebb and flow, and really the Eastern empire never put much into the province, in terms of attention or resources, especially after Justinian died. Spania was a long way away, and there were other challenges closer at home; religious controversy, the ever present threat of Persia, nomads from the steppes. It was probably mostly thought of as a buffer for the richer African provinces, to protect them from raids or attacks by the Visigoths in imitation of the Vandals, and in that sense it was successful, no such attack ever took place.

Well, a shortish episode, but a dense one. The Visigothic kingdom, in the space of fifty years, passed through phases of defeat, foreign domination, and internal strife. While I’ve mostly spoken of Hispania in all this time, the real center of the kingdom remained the mostly urban, heavily Romanized coastal territories from the Rhone to Barcelona, though gravity has been pulling focus southward.

The king we finally landed on today, Athanagild, had no sons, and so the Visigoths looked set for another round of conflict over the succession. I know that sounds a bit tiresome, so before I talk about that, we’ll talk about the Athanagild’s daughters instead. It will give us an opportunity for some of the interpersonal drama and gossip that’s been missing from these last few episodes of battles and successions. It will also give us a look-in on goings-on in Francia without losing focus on the Visigoths. That sounds like a bit of a narrative nightmare now that I say it out loud, but I do enjoy a challenge every now and then.f the goal of the murder was to prevent Byzantine occupation and domination, then it was a wasted effort. In return for their help – which must have been significant in some way we just can’t see – Athanagild recognized direct Byzantine sovereignty over a stretch of southern Hispania, more or less consistent with the province of Baetica, which was named by imperial administrators Provincia Spaniae – finally dropping the H. Over the years this would expand and contract, as stronger and weaker Visigothic kings sought to win back what had been given away. Low level conflict along this border would ebb and flow, and really the Eastern empire never put much into the province, in terms of attention or resources, especially after Justinian died. Spania was a long way away, and there were other challenges closer at home; religious controversy, the ever present threat of Persia, nomads from the steppes. It was probably mostly thought of as a buffer for the richer African provinces, to protect them from raids or attacks by the Visigoths in imitation of the Vandals, and in that sense it was successful, no such attack ever took place.