Hello, and welcome to the Dark Ages Podcast.

Episode fifty-one: Liuvigild and the Search for Unity

I’m as tired of saying it as I’m sure you all are of hearing it: sorry for the long absence again. There’s not much I can say, except I’m sorry. Life has thrown curve ball after googly this year, and I have no confidence that it won’t continue to do so. We all continue to do our best with what we are given.

That’s apology number one out of the way, but I have another. At the end of the last episode that I did drop, back in July … ugh, I promised to talk about, well, let me just quote myself: “about Athanagild’s daughters instead. It will give us an opportunity for some of the interpersonal drama and gossip that’s been missing from these last few episodes of battles and successions. It will also give us a look-in on goings-on in Francia without losing focus on the Visigoths”. I also noted that it sounded like a narrative nightmare. Dear sweet listener, when I tell you that I was right about that, beyond my wildest expectations, I am not exaggerating in the slightest. As I attempted to write that episode, it became more and more obvious that I what seemed like a dip of the toe into the Frankish waters would turn out to be more of an extended bubble bath in the suds of the Merovingian family tree, with candles and a glass of wine, and I haven’t even run the tub yet. Meaning I was not prepared to deal with the complexity, nor have I laid sufficient groundwork for you to be prepared to follow me. So I will have to leave the story of the unfortunate Galswintha, princess of the Visigoths, to the side until later.

That being the case, I left you all in an awkward place last time. We were in the middle of the barely recorded reign of Athanagild, with no obvious big events on the horizon, so what are we going to talk about instead?

Easy answer, we’re going to keep on truckin with the Visigoths and their continued search for stability after the Balt Dynasty finally ran into the sand. If you’re listening to this in the future, you just heard all about this, but in case you are listening in real time, I’ll quickly review the situation in Hispania when we left it, then finish off the fairly obscure reign of Athanagild – that won’t take long – and finally introduce Liuvigild, the first Visigothic king since Alaric II that had the opportunity and the wherewithal to rule strategically rather than reactively. We’ll talk mostly about his military undertakings, and next episode talk about his religious endeavors and attempt to finally integrate the Visigoths with the native Hispano-Romans.

First, to review:

The last king who could claim descent from Alaric the First – Amalaric – at first ruled under the regency of his Grandfather Theodoric the Great before coming of age in 522 and sole rule in 526. He was defeated by raiding Franks and either assassinated by his own men or by Frankish agents in 531. That left the board wide open for the various Visigothic noble clans to attempt to find a new king from among their own number. The problem with these situations of course is that every family is convinced of their own right to rule, and violence is often seen as the answer. The Visigoths were able to stave off civil war by electing one of Theodoric’s generals, who ruled relatively successfully until 548, but upon his death, the Visigothic elite entered a long period of dynastic struggle.

In the later stages, one of the contenders asked for assistance from the Empire, and Justinian, ever willing to push his influence further into the old Roman lands, dispatched an expeditionary force. This small force arrived in 552, and initially they were commanded by a patrician named Liberius, who has appeared on this podcast off an on all the way back to episode ***, when he worked for Odoacer in Italy. They allied with Athanagild in a campaign against his rival Agila, but how much help they actually offered is unclear, since the civil war carried on for another two years. In that time, the Byzantine force made themselves obnoxious to both sides, and became a third, destabilizing force in the conflict. Eventually concerns over Byzantine influence prompted the Visigothic nobles to kill Agila and unite behind Athanagild.

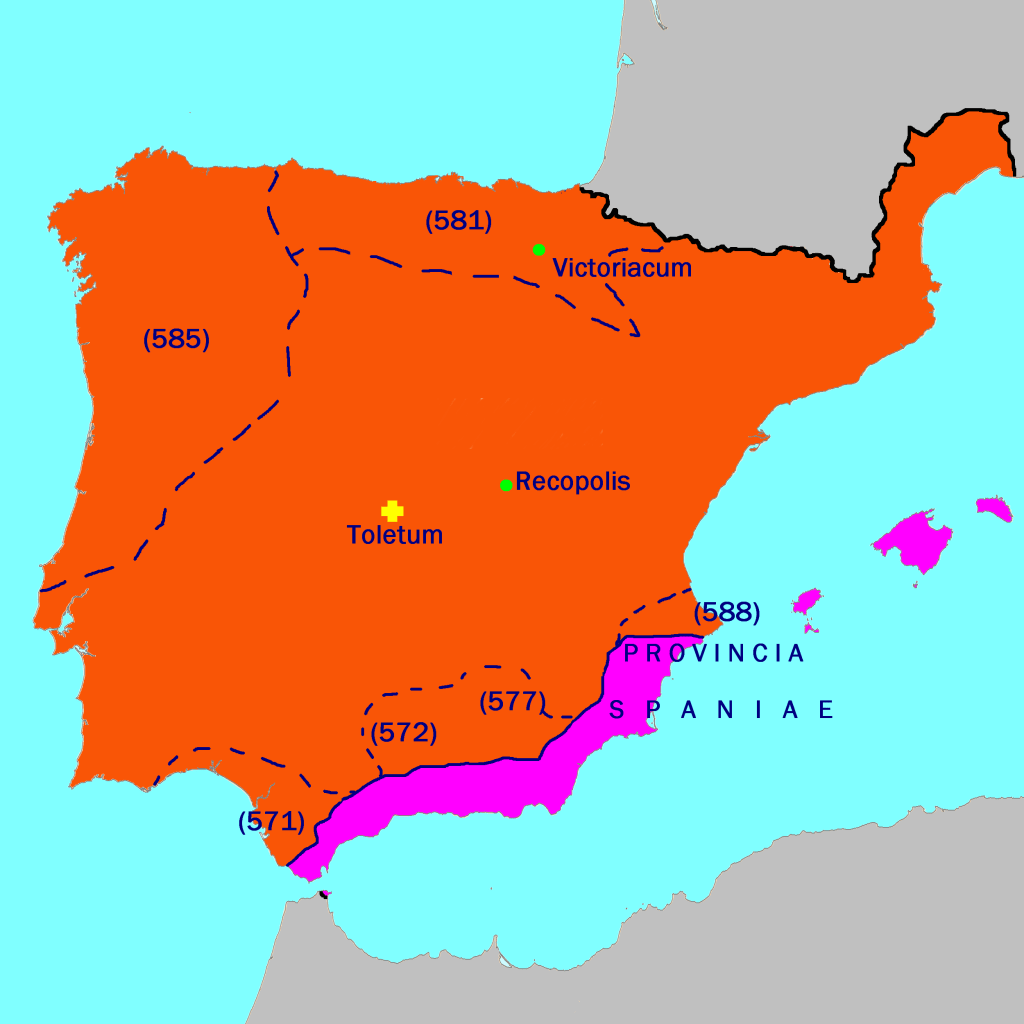

Athanagild pushed hard to remove the Byzantines from Hispania, but was unsuccessful. There are few details about these conflicts, but we have to assume that there was a more or less constant state of war along the edges of Byzantine territories. Roman influence ran along the southern coast, from Medina Sidonia, just west of Gibraltar, all the way to Cartagena. Essentially we’re talking the rich, olive oil producing lands of Baetica, or at least the southern half of it. Historians are divided about how far inland the Byzantines extended their influence in these first few decades – whether it was as far as Cordoba, for example, but that kind of nitpicking is a bit beyond our scope I feel, the frontier moved in and out as fortunes waxed and waned.

Most interesting to me, is the shift in attitudes that becomes apparent with the arrival of these Eastern invaders. They were seen as just that – invaders – even by the non-Gothic, formerly Roman inhabitants of the region. Like Italy, Hispania had never been under the control of Constantinople, and these Greek-speaking parvenues were just as foreign as the Goths once had been. We are now almost a hundred years out from the dissolution of the empire, long past any meaningful living memory, and mindsets are beginning to change.

I am still referring to the Goths as identifiably separate from the native hispano-Romans, especially at the elite levels of society, and that division remains clear. It breaks down along lines of religion especially, maybe language and material culture too, although that is less clear. But if the locals still don’t identify with the Visigoths, and Romanitas isn’t really available as an option anymore, how do they see themselves?

For an answer, we have to read between the lines of our sources, and look to archaeology for help. Of all the places in the old empire, Hispania’s urban life seems to have been the least disrupted by new circumstances. This was especially true in the coastal cities and the wealthy centers in the Ebro and Guadalquivir Valleys. Many of these cities, like Merida in the South or Zaragoza in the north, had been founded at the time of the original Roman occupations, now almost seven centuries ago. Others, like Medina Sidonia, were even older than that. The city seemed to be the center of most Hispano-Romans’ loyalty, and when Isidore or the other chroniclers of the period refer to “citizens” they are invariably referring to the residents of a particular town or city, not to either Roman citizens, or to citizens of the Visigothic kingdom. Since well before the actual “fall of Rome”, there had been this tendency toward parochialism, focus on the locality, and cities could provide a basis for such focus.

Christianity strengthened these local identities, even as the idea of a universal church was preached and extolled. Each city had its own patron martyr saint, dating back to the time of conversion and persecution. The stories of these martyrs were effectively stories of the city’s refounding, and the saints served as First Citizen of the newly created city of God existing alongside the secular City of Men.

Veneration of Saint Eulalia in Merida or Saint Vincent in Zaragoza replaced the Civic religion of Roman paganism, and church building and processions were expressions of unity and faith for the communities that lived under their own Saint’s protection. Isidore even credit’s Agila’s misfortunes to the punishment of Saint Acisclus of Cordoba.

The centrality of Christian worship naturally enhanced the prestige of bishops. I haven’t related much about this, but large swathes of the chronicles are taken up with the successions and activities of bishops. I haven’t troubled you with it, since it is intensely parochial and often confusing, but it is there, and bishops were as much leaders of their cities as were the local councils of elites or the count who represented the King’s interests. It’s also notable that Bishops at this time, more often than not, bear Latin names, while kings and generals have Germanic names.

The Byzantine armies who landed on the southern shores of Hispania may have thought of themselves as restorers of the Roman empire – their emperor certainly did – but found that the locals were not particularly keen on such a restoration. While Romanitas as a marker of culture, especially among the elites, remained powerful, as a political identity, it had faded. The prestige of Roman citizenship had in fact been fading for some time before 476, since it had become less and less exclusive and therefore less useful to political elites.

Roman Citizenship had been replaced by local citizenship and loyalty, and these newly arrived eastern troops were met with ambivalence at best and sometimes hostility. That led commanders to take oppressive measures to ensure local compliance, which of course only hardened resentments toward them. The residents of Hispania were not integrated with their Visigothic rulers, but neither were they unambiguously Roman, or willing to submit to the remote Roman emperor merely on the basis of his position. I’m making all sound very adversarial, but citizenship of a city didn’t necessarily stop anyone from identifying with any other group. Like through most of history, it’s probable that most people, even people in authority, did what they could to keep life ticking along as normally as possible in whatever circumstances, which would sometimes require some flexibility.

By the way, I’m aware that I’ve been using Byzantine and Roman pretty much interchangeably this episode. I’m sort of doing it on purpose. Internally, the Eastern Empire never stopped referring to themselves as the Roman empire, and there was indeed an unbroken continuity of government in Constantinople from its founding until its fall in 1453. That being said, there is also unquestionably a cultural gap between East and West that only widens as time goes on. In my mind, the break between Rome and Byzantium arrives with the death of Justinian, in 565. Justinian was the last emperor who spoke Latin as his native language, though it remained the language of administration for another fifty years. His great project, the restoratio imperii, was not taken up again by his successors, and the empire increasingly turned inward to its own religious controversies, and eastward toward the threats of Persia and later Islam. So just as the culture and priorities of the Romans become ever more Byzantine, so will the nomenclature of this podcast.

The Byzantines in Hispania refortified towns in their own idiom, built churches and new administrative buildings, and there was still no arguing either with their know-how.

Nor were their intentions obscure; they meant to stay, even if it was just on the southeastern coast, and their presence was a constant threat to any Visigothic ruler.

The last decade of Athanagild’s life was spent attempting to extirpate the invader. It was an old story; the Visigoths could raid and ravage the countryside without much difficulty, but breaching fortified cities and towns was often beyond them. Time, supply issues, and the strength of Byzantine fortifications meant that while Athanagild and Agila managed to retake most of the Guadalquivir Valley, the imperial province of Spania, with its capital at either Malaga or Cartagena, remained un-extirpated.

Athanagild based himself in Seville for the nearly continual campaigning, but little else is known about his reign. Some efforts at a rapprochement with the Franks were made; Athangild’s two daughters were married to Frankish kings, though with mixed results that I’ll surely get back to in a later episode. What few passing references there are to the king are generally uncomplimentary, but there simply isn’t enough information available to us to make a definitive assessment of his leadership.

Athanagild died in 567 or 568, about two years after Justinian. He was about fifty years old, and he had ruled the Visigoths for a fractious thirteen years, but managed that rare achievement of Visigothic kings, dying of natural causes.

He died in Toledo, which, with its central location, was becoming an important city of the Visigothic kingdom, though not yet the official capital.

Athanagild had no sons, and as mentioned his daughters had been married into the Frankish royal house, so once again dynastic ambiguity threatened civil war. Isidore gives us close to zero information about what happened next, noting only that there was an interregnum of five months. Other sources are no more helpful.

That would have seemed to have been an opportune moment for the Romans to push to expand their influence, but no such campaign was mounted. Justinian himself had seemed disinclined to push the issue of Hispania too hard, and his successors were even less interested. The general consensus among historians is that the Empire intended Spania as a buffer between the newly reconquered African provinces and Visigothic aggression. The war in Italy had been long, grueling and expensive, and there was little taste in Constantinople for more extended foreign adventures in the west. So the Visigoths were able to spend the time after Athanagild died to settle the succession problem without interference.

At the end of these five mysterious months, a new king was elected from among the noble Visigoths. Named Liuva, he was elected at Narbonne, the first king to be crowned in Septimania since Amalaric. The northern crowning may be an indication that trouble with the Franks was flaring up again, and the fighting men were close to where the action was. If that was the case, it may also have been the catalyst for the election taking place at all – in the face of a threat, a central leader was needed.

We know nothing about Liuva’s life prior to his election. He based himself in Narbonne, further suggesting trouble in the north, and in 569 took the unprecedented step of dividing the Visigothic realm with his brother, Leovigild. Liuva remained in Septimania and dealt with whatever it was that needed dealing with up there, while Leovigild set himself up in Toledo to run the southern and eastern parts of the kingdom. This seems to have worked well enough. If there were frictions, there wasn’t time for them to wear down anything important, as Liuva died suddenly in either 571 or 573, after just four or six years as king. Leadership of the whole Visigoth kingdom passed smoothly into Leovigild’s hands, and he shored up his legitimacy by marrying Athanagild’s widow, a woman named Gosuinth. It’s a move we’ve seen a few times before, associating oneself with the previous dynasty through marriage.

Compared to Athanagild, Liuvigild’s reign is a whirlwind of activity, accomplishment, and other words that begin with A. The contrast is most likely thanks to the presence of a competent chronicler for his rule, John of Biclaro. John’s chronicle, as I believe I noted earlier, was a continuation of another chronicle, by Victor of Tunnunna, and is effectively our only source for information on this period of Visigothic Hispania. Athanagild was almost certainly at least as active as his successor, he just didn’t have the good fortune of a committed chronicler.

That being said, Liuvigild’s activity was undoubtedly effective, and if we’re scoring based on results, then Liuvigild is way ahead of Athanagild on points.

The most constant and unsurprising pastime for the new king was war, and would be for the entirety of his tenure. I’ve framed these as defensive, and in the case of the Byzantines and the Franks, that is probably largely accurate. But let us not forget that the loyalty of a king’s fighting men was assured by his ability to reward them, and to do that, he needed a steady income in the form of spoils. Which is a nice way of saying “stuff taken from dead neighbors”.

Isidore, with his anti-Arian bias, frames Liuvigild’s campaigns of expansion as motivated by base greed and ambition, and no doubt Liuvigild was ambitious. He mounted a campaign, whether expansionist, defensive, or punitive, in almost every single year of his nineteen year reign.

He started sole rule off by sacking the Roman-occupied towns of Baza and Malaga. This campaign passed through a mountainous territory called Orospeda, which is not firmly identified. It was definitely an inland buffer territory between Byzantine and Visigothic lands, with local power structures independent of either of them. Several such territories existed in the frontier regions between the various powers of the Iberian peninsula. We have very minimal sources for how or if such territories were governed; they could have been a collection of relatively powerful or stubborn towns or fortresses, or they may have been linked by a confederation of some kind. Individual circumstances varied, of course, some probably were loosely connected cities, others were centralized enough to issue their own coinage. John mentions the “senate of Cantabria”, in the north, but whether such a body was a leftover from the days of empire, a new creation that had thrown off foreign domination, or an ad hoc body of local elites that met in their spare time, we just can’t know for sure. The information just isn’t there, other than the clue that they are referred to as unitary entities by the chroniclers.

The sack of Baza and Malaga was followed the next year, 571, by the capture of Medina Sidonia, thanks to a cooperative local on the inside. Gains in the south continued with the capture of Cordoba, though in this case John of Biclaro tells us that it was “in rebellion” not occupied by the Romans. He also tells us that Liuvigild’s victory came “after having killed many peasants”. It’s an odd detail to include, and the scale of the slaughter must have been significant to warrant a mention. It may be that the campaign was simply particularly violent and destructive. Possibly, though, it may be that these peasants had organized themselves into bandit armies – what we used to call bagaudae in the fifth century – and were symptomatic of the continual chaos along the Roman frontier.

Calm, if not exactly peace, seems to have descended in the south for a while after this massacre, and Livigild looked to the northwest for further diversions. The chaos in the kingdom of the Suevi allowed space for several of those more-or-less independent counties I mentioned earlier. Liuvigild began to pick these off, starting with Sabaria, today the area west of Valladolid between Benavente and Salamanca. The following year he continued on to take control of mountainous Cantabria, or at least the southern half of it. Spooked, the king of the Suevi, Miro, agreed a treaty with Liuvigild, agreeing to pay tribute to the Visigothic king.

These victories provided the cash Liuvigild needed to maintain his fighting men, along with the prestige that could help carry his dynasty forward. That dynasty in this case, being represented by two sons, Hermenegild and Reccared.

Liuvigild’s sons were important to him, beyond what we might expect of just a parent. Liuvigild would have been aware of the, shall we say, unsettled relationship between the Visigothic nobility and their monarch. He himself had come to power fairly smoothly after his brother’s death, and he sought to ensure that the same spirit of concord would favor his sons and ensure his dynasty and legacy. The two were about 10 and 8 at the time of their father’s accession to power, and he made a point of giving them responsibilities and visible positions from an early age. He gave the administration of Sabaria to them when Hermenegild, the elder, was around 15, a perfectly reasonable time for young men to be assuming the duties of manhood at the time. More importantly, these kinds of positions marked the boys out as co-regents, got people used to seeing them in positions of power, and hopefully squashed any ideas the other nobles might have had of reaching for the prize when the old king croaked.

But, lest you decide that this podcast really is just a catalog of geography and fighting, let’s talk a bit about what Liuvigild did when he wasn’t busy bashing someone over the head.

Because here, for the first time in a long while – probably since Euric – we have a Visigothic king who can capitalize on his military success.

Let me demonstrate the extent of Liuvigild’s ambitions by taking you, in your mind’s eye, to a dusty plateau above the River Tagus, near the little village of Zorita de los Canes. The ruins of a large stone building stand against the horizon, seemingly isolated. As we approach though, we can see that it is surrounded by the foundations of other knocked down buildings, dozens of them. There are the clear outlines of a square in front of the remaining building, and of a defensive wall along the edge of the plateau, with spaces within it, forming a kind of gallery maybe on the inner side of the wall. It’s clear that, were you to dig a little, there is more to be found underneath the surrounding olive trees. The standing building’s footprint is a cross, with rather short, stubby arms; there are the remains of an arch at the end, where the semi-circular apse would have hosted the altar, for this was very clearly a church.

These are the remains of Reccopolis, a city founded by Liuvigild around 578. According to John of Biclaro, “tyrants had been extinguished on every side, and the invaders overcome”, and the city was raised in celebration of victory and named for the younger prince, Reccared. This is not to say that the Byzantines had been expelled, but that the last of those border statelets – Orospeda, had been brought to heel – twice actually: a conquest, followed almost immediately by the vicious stomping of an uprising.

Historian Michael Collins casts doubt on the idea that the city was named for Reccared, if that were the case, the name should be Reccaredopolis, city of Reccared, not Reccopolis, city of Recc. After all, it was Constantinopolis, not Constanopolis. Possibly it’s a mistranscription of Rexopolis, city of the king. That’s all mindless waffle though.

Reccopolis was divided into an upper city and a lower city. The upper city included the palace, with administrative buildings, a mint, granary, and church attached, while the lower city would have housed the majority of the population. Protected by walls studded with towers, Reccopolis was fed by an aqueduct and hosted several markets.

I have gone on and on about the decline of urban life in the Western empire, and even in Hispania, where the trend was less pronounced than elsewhere, secondary settlements often disappeared over the course of the fifth and sixth centuries. Across Europe, between the fifth and eighth centuries, only a handful of new cities were founded, and Reccopolis is one of them. The Visigothic Kings would establish a few others in the following centuries, but Reccopolis is the first, and the one with the most established history. Its church was also probably the last Arian church built by the Visigoths. Full disclosure here, the standing ruins are actually those of the later hermitage of Nuestra Señora de Recatel; built over the palatine chapel’s foundations, and still old, but not part of the original city’s plan. Pictures of the site will be on the instagram site and at Darkagespod.com.

Founding a city was followed up by adjusting the Law, as Liuvigild worked through his checklist titled “things good kings do”.

He reformed the legal codes laid down by Euric, though no significant text of these reforms survives. We do know, significantly, that a law forbidding Goths from marrying native Hispano-Romans was done away with.

That’s worth exploring a bit, isn’t it? Why would he do that? Just thinking out loud here, but maybe it was because such marriages were already happening, in defiance of the law, and happening in great enough numbers that Liuvigild just threw up his hands about it? Maybe, but I think there’s something deeper at play. In spite of the constant warring against the Byzantines in the South, Liuvigild and his peers considered themselves the successors of the Western Empire, not its destroyers. That’s evident from the fact that most Visigothic kings took the Roman name Flavius when they came to the throne, heavily associated with the imperial power. Coins were minted in the style of the western empire, though with less expertise. Latin remained the language of government, law, and learning. Separation between the old citizens and the Goths implied a situation that the Gothic kings did not want – they did not want to be seen as occupiers of Hispania, but as the natural leaders that carried on in the traditions of the old empire. Whether the rest of the Gothic nobility felt the same way is debatable; we’ve already seen resistance to Romanization among the Ostrogothic elites in Italy. Marriage between Goth and non-Goth would allow for both cultural integration and acceptance, and for Gothic families to access the settled wealth of the agrarian economy more directly than through taxation or expropriation. The decriminalization of mixed marriages is the first act by a Gothic king – either Visi or Ostro – that seems aimed at erasing the barrier between barbarian and Roman.

The stumbling block that stood right in the middle of the road to integration was religion.

Obviously.

The Orthodox bishops, mostly hispano-Roman, would not and could not accept the Arianism of their Gothic military leaders. And let me not give the impression that this hostility ran only one way; the Arian clergy were just as adamant about the errors of the Orthodox. And so the separation remained.

On that checklist of his, there was one other item just begging to be crossed off; ensure religious harmony. If he could bring political unity to the Visigoths, found cites, and make laws, surely Liuvigild could put together a religious consensus. How hard could it be? It was only a four hundred year divide weighed down with all kinds of cultural and political baggage. Should be a cakewalk.

We will talk about all the ways it was not a cakewalk next time, with the … possibly … tragic story of Liuvigild and his sons.

Until next time, take care.