511 to 532

Hello and welcome to the Dark Ages Podcast. Episode 56: Sons of Clovis.

The time has come, my friends, to speak of shoes and ships and sealing wax, of cabbages, but mostly of kings.

Four kings, to be exact, the four sons of Clovis I. A still undetermined number of cabbages. Maybe we’ll find out in the course.

Before we get started though, there is an issue I need to address. It has to do with the last episode, and it is, well, embarrassing. You’ll probably remember the part last time where I spoke, at some length, about wooden tools. About how iron tools were rare and precious, and mostly used to make more wooden tools. Dear listeners, it has come to my attention that in that whole section of the podcast, talking about wooden and iron tools, that I did not tell one Minecraft joke. Not one! I am mortified. Please rest assured I am working on myself, and I will do better in the future. I only hope you can all forgive me.

Okay let us try to move on.

Clovis and Clotilde

Clovis died in 511, as I’m sure I’ve told you many times before. He had united all the petty kingdoms of the Franks and taken control over most of the old Roman province of Gaul, and quite a bit of non-Roman territory across the Rhine as well. Along the way, he had married Clotilde, a Burgundian princess and as formidable as Clovis in her own right. Also the patron saint of Normandy, fun fact there. She gets to be a saint because it was by her influence that Clovis, in the year 500, had converted to Christianity, and brought his people along with him, at least nominally. Importantly, it was Orthodox, or Catholic Christianity, which at this point in time are one and the same thing. It was not the heretical Arian Christianity of many of the other Germanic tribes, most notably the Goths. Clovis’ acceptance of the Roman version of Christianity meant that moving forward, the Franks would be more quickly integrated with the Gallo Roman society over which they now ruled. Long term, that would turn out to be an advantage.

Children

Clovis and Clotilde had three sons and a daughter, and Clovis had an older boy by an earlier relationship, either an earlier wife or a concubine, we don’t know which.

The sons were, in order of birth:

Thiuderic, the eldest and half-brother to the other four. It’s hard to see at this distance, but there are straws in the wind that he and his step mother were not overly fond of each other. Thiudebert was probably around 8-10 years older than his eldest half-brother.

That brother’s name was Chlodomer, born probably around 495. Next was Childebert, two years or so later, and finally Chlothar, born around the time of his father’s official conversion, i.e. around 500. The spelling of all these names can vary wildly, depending on who you’re reading. For example, you’ll often see Chlothar anglicized as Lothar; meanwhile the French call him Clotaire. I’ve taken the extremely unscientific approach of using whichever spelling I first encountered, unless it’s too hard to pronounce. If you don’t look at the transcripts, you won’t care much about that anyway, but I thought I’d mention it.

My plan for this episode is to tell one story from the life of each son, though they do overlap quite a bit, as you’d imagine, and by so doing build a picture of the personalities at play, as well as the first decade and a half or so after Clovis’ death.

Now wait one second, I hear you saying, you said there was a daughter, what happened to her in your list, Mr. Chauvinist Pigman?

And yes, you are right, I mean not about the insult, but Clovis and Clotilde did have a daughter, also named Clotilde. I’m going to institute a convention and refer to the younger one as Clotilda, to distinguish her from her mother.. Her story is directly tied to her brother Childebert, and unfortunately she died fairly young, and so ends up as a supporting character rather than having her own narrative. C’est la vie au moyen âge.

We’ve met Clotilda before, but I suspect I called her just a Frankish Princess to avoid introducing too many names at once. No such restraint is possible in this episode, I’m afraid. There will be names, I’m afraid. Yes, even beyond the ones I’ve just introduced.

I have four stories to tell about these four brothers, to build a picture of the way Francia fit in with the rest of its neighbors, as well as how they all interacted with each other. It seems, basically, that at least some of the external warring was a way to sublimate the rivalries between the brothers, and prevent them from becoming unproductive internal conflict.

This is a story-heavy episode. What I mean by that is that I will be recounting the stories recounted by Gregory of Tours, with not much in the way of analysis or debunking. Lean a little bit into the fun, if you will. Some of it, I am warning you now, is pretty brutal, so be aware.

I will also be playing fast and loose with chronology. Don’t worry too much about dates. I’ll signpost the ones that matter, and to be honest, Gregory’s accounting is far from clear anyway. Okay? Can we all live with that?

Then let’s begin by setting the scene.

The Frankish Inheritances

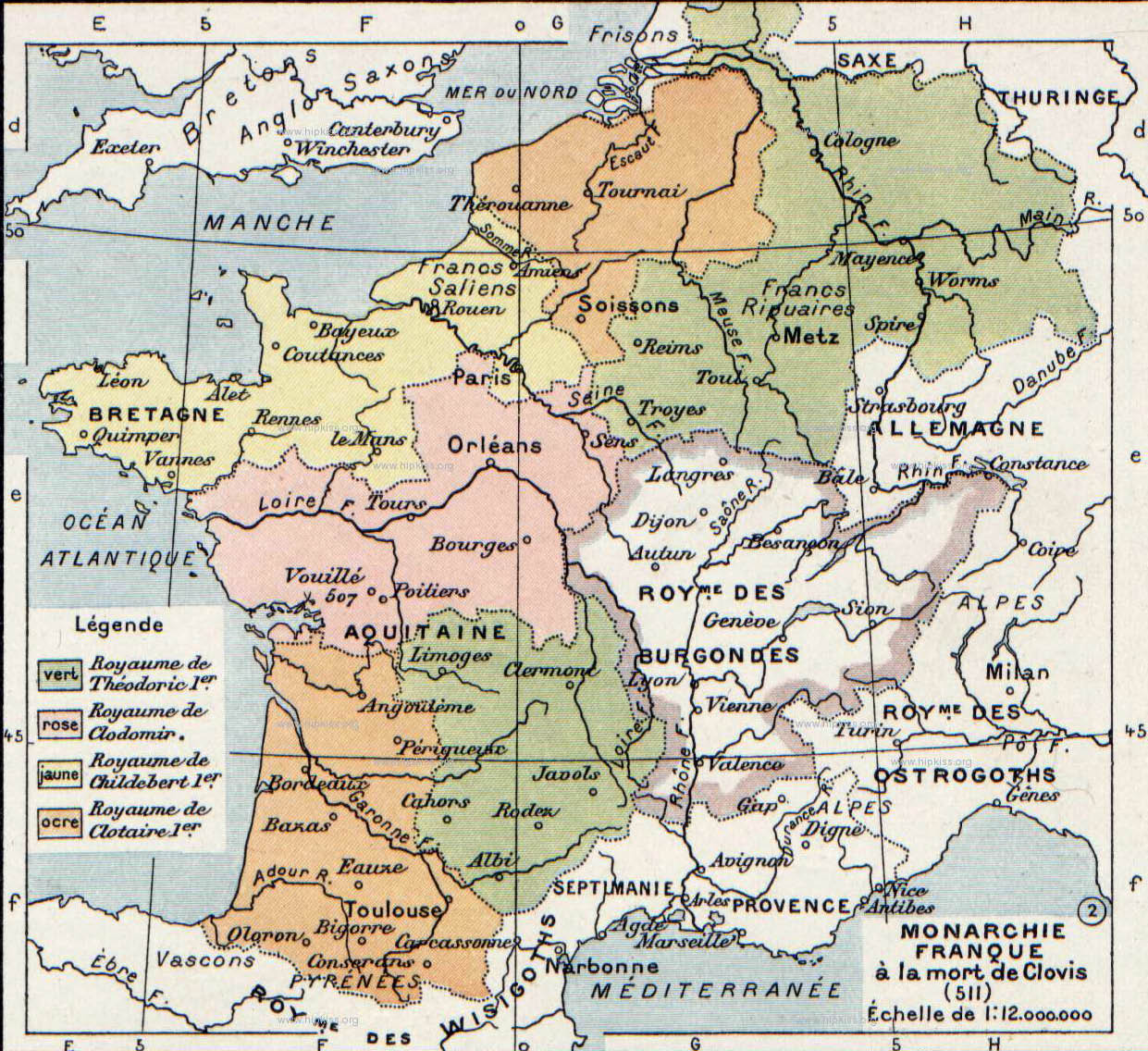

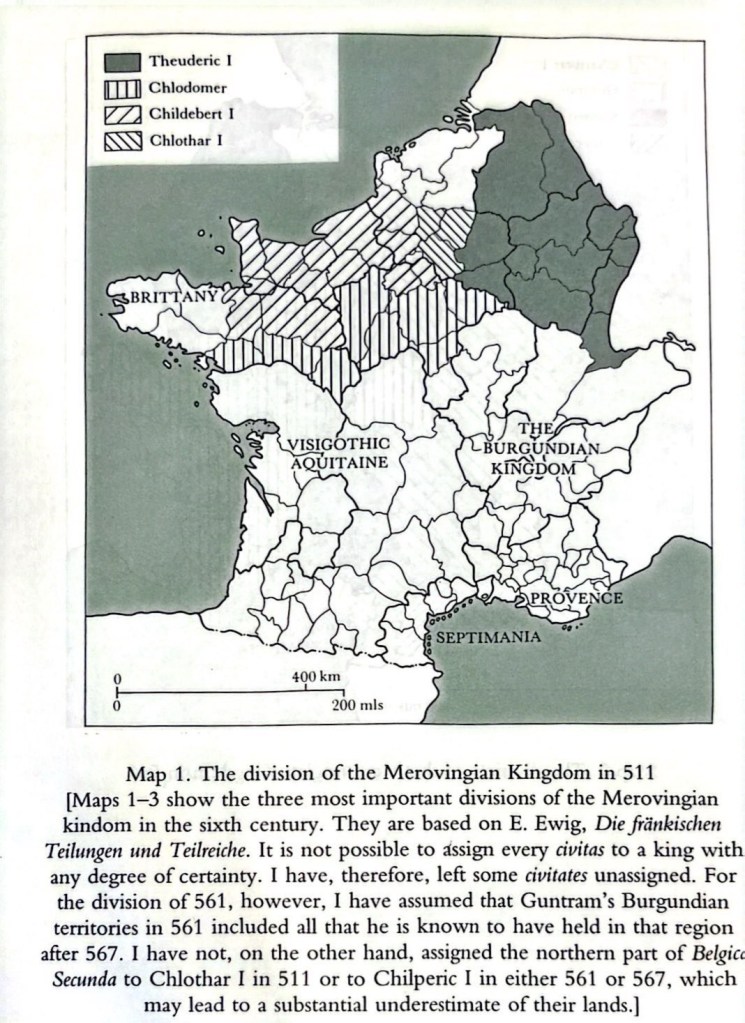

Francia would eventually be divided into four reasonably defined kingdoms, but Clovis’ division of his realm was less consolidated, and each brother received lands that were not necessarily contiguous. Who got what has had to be reconstructed, by the way, and sources differ. Gregory doesn’t actually give details about how the kingdom was divided among the sons. He does give details about the division among the next generations, and historians have had to work backwards from that. The map that appears most commonly on the wikis, for example, comes from Paul Vidal de la Blanche in 1894 and is very extensive, but probably overstates the degree of control over the territories each king had, especially in the South. Historian Ian Woods provides a much more conservative idea of each son’s zone of control. I’ll put both maps on Instagram so you can compare them. In both cases, the historians involved are attempting to piece together a map from the available historical record and later descriptions of the kingdom’s divisions.

Most sources you read will say that the division of the lands was in keeping with Frankish custom, but there’s not really any firm evidence for that one way or another. We just don’t know enough about the customs of the early Franks to be sure. It’s possible the division came about at the urging of Queen Clotilde, in an effort to avoid her own sons being sidelined in favor of the elder Thiuderic.

Each brother chose a city as the center of their rule, though that doesn’t mean that they were there all the time. As a result, each one is sometimes referred to as king of their primary city. Broadly, we can say that Thiuderic received the northeastern parts of Gaul, along with some amount of territories beyond the Rhine. He seems to have had some kind of authority in the Auvergne, at least he felt empowered to lead a punitive campaign against some kind of rebellion there in 524 or 5. His primary city is usually identified as Rhiems.

Chlodomer received lands along the Loire, seemingly in a broad band across the middle of Gaul, from Nantes to Orleans, and maybe as far as Troyes. His power centered mainly on Orleans.

Childebert’s territories were mainly in the northwest, including what would become Normandy, Maine, and the Ile-de-France. Paris is usually identified as his city, though in Gregory’s narrative, Paris also seems to be a kind of neutral ground where the brothers could meet..

Lastly, the youngest brother, Chlothar. Here is where we find the greatest disagreement between the earlier and later historical evaluations. Vidal-LaBlanche gave him all of Aquitaine, along with holdings in the north like Flanders and Soissons. Woods whittles that down to just the areas around Soissons, maybe as far north as Tournai, but not much more than that.

Ultimately, my advice is to just not worry about the details of the divisions too much. We won’t have a solid, definitive map until around 561 anyway. There’s going to be so much swapping and changing, trying to hold on to any kind of defined map is going to be mostly wasted effort, for the next few episodes at least. Not to mention since the brothers frequently teamed up in various combinations, the actual divisions are of only limited relevance in the grand geopolitical scheme. I will point out though, that as far flung as the brothers’ territories seem, their primary cities – Paris, Soissons, Orleans, and Rheims – are all within easy reach of each other. The furthest apart are Orleans and Rheims, at 175 miles (280 km). A fair distance for an army or a fully kitted out royal household, but a messenger on horseback could easily cover the distance in a few days. The idea was clearly that the brothers keep in touch with each other, and they did, as we will see. Throughout the Merovingian dynasty’s existence, there will always be only one Francia, no matter how many kings it might have at any given time. And Francia, as far as its kings were concerned, could be bigger.

Neighbors

Out of these four brothers, not one of them was satisfied with what they had. Surprising, no? Each and every neighbor presented at least the potential for expansion.

To the south, the Visigothic kingdom was still reeling from defeat at Vouille, and in addition to the plundering opportunities of northern Hispania, they still clung to Septimania, and its valuable ports. Francia, large though it may have been, still lacked an outlet onto the Mediterranean, and so lost out on direct access to the most lucrative trade. Access to the Rhone was also limited by the presence of the Burgundian kingdom. Last time I mentioned that the Burgundians controlled the Rhone from Geneva down to Avignon, but that’s actually understating the extent of the kingdom, which extended influence as far north as Dijon. The Burgundians were Catholic Christians, and had a strong relationship with Constantinople. Burgundia was not a force to be taken lightly.

Continuing around counter clockwise, the Alamanni occupied the right bank of the upper Rhine, guarding the northern ends of the passes into Italy. Theodoric the Great had cultivated relationships with this Germanic confederation, and they enjoyed his protection, as long as he wasn’t distracted by anything else. Lastly, to the east, along the lower Rhine, the Thuringians. Clovis had been nibbling at their edges already, and his eldest son Thiuderic would continue to work that furrow, picking fights and sowing discord within the Thuringian ruling house.

The Thuringians were ruled by three brothers. I know, more brothers. These were Hermanfrid, Berthar, and Baderic. Hermanfrid and Berthar fought over the division of their lands, and Berthar was killed. Baderic and Hermanfrid then split the remaining Thuringian lands equally between them.

Thiuderic and the Thuringians

There is a theme in Gregory’s stories of ambitious women goading their husbands into battles, and that’s also the case here. Hermanfrid came into his hall one day for a meal, and found that the table was only half set. When he questioned his wife about this, she told him that “a king who is deprived of half his kingdom deserves to find half his table bare”. This sounds like a pretty petty thing to trigger a war, but remember that this meal wasn’t being served at a cozy table for two with a candle and flower vase. Eating alone would have been a vanishingly rare occurrence for a major lord, and a failure to provide for half of the people who had shown up in his hall expecting his generosity would be a shame and humiliation. So Hermanric went looking for friends.

He made contact with Thiuderic, and suggested a joint operation against Berthar, offering to share any territory gained equally between the two of them. Thiuderic readily agreed, and the two leaders invaded Berthar’s territory from east and west. Berthar committed a tactical error, and allowed the two invaders to link up. When they met in open battle, the two allies overwhelmed Berthar’s force, cornered him, and cut off his head. Thiuderic went home, whistling happily, and waited for Hermanfrid to begin the process of transferring his share of Berthar’s lands. And he waited. And he waited.

Gradually it began to dawn on Thiuderic that Hermanfrid may have been fibbing. Fibbers made Thiuderic grumpy, and he called on his little brother Chlothar to come and help him right this wrong. Chlothar agreed, and Thiuderic gathered his men around him and gave them a little pep talk. He reminded them that the Thuringians had been raiding their lands for years, and rattled off a litany of the various war crimes they had committed against the Franks. If you’re feeling squeamish, turn away now. Gregory reports Thiuderic’s speech thus:

“Remember that not so long ago, these Thuringians made a violent attack upon our people and did them much harm. Hostages were exchanged and we Franks were ready to make peace with them. The Thuringians murdered the hostages in all sorts of different ways. They attacked our fellow countrymen and stole their possessions. They hung up our young men to die in trees, by the muscles of their thighs. They put more than two hundred of our maidens to death in a most barbarous way …” I’m going to stop there, the barbarous way involves carts and horses and it’s honestly just too gross.

What’s interesting to me about this speech isn’t the litany of horrors, but the fact that Thiuderic clearly feels the need to justify himself to his army – or at least his commanders. Thing is, society was largely flat, there was probably no more than one level of command between the king and Frankie Spearman. These are freemen, remember, they belong to themselves; they owe an obligation to their lord to fight for him, but if their lord starts leading them off into unnecessary or unprofitable wars, they could easily decide that their obligations only go so far.

Thiuderic and Chlothar advanced into Thuringia and met Hermanfrid on an open plain. Hermanfrid had had time to prepare; his men had dug trenches across the plain and then covered them over again with branches and turf. Gregory describes the battle: “When the battle began many of the Frankish cavalry rushed headlong into these ditches and there is no doubt they were greatly impeded by them. Once they had spotted the trick, they advanced with more circumspection. King Hermanfrid was driven from the battlefield and the Thuringians realized that they were being cut to pieces. They turned in flight and made their way to the River Unstrut. Such a massacre of the Thuringians took place here that the bed of the river was piled high with their corpses and that the Franks crossed over them to the other side as if they were walking on a bridge.”

The Unstrut, if you look it up, is deep beyond the Rhine, a tributary of the Saale. It originates near Dingelstadt and forms the heart of the Thuringian basin. And if you think I told you all that just so I could say Dingelstadt, well I don’t know what to tell you.

After the battle, Chlothar avoided a hamfisted assassination attempt by his brother, and then selected his share of the spoils. Among other things he took Radegund, the daughter of the king Berthar, and shortly thereafter had her brother murdered, presumably to snuff out any competing claims to Thuringian territory and preempt a blood-feud. You remember the largely positive spin I gave the practice of wife-napping in the last episode? Well, here’s the counter example. Given what we’ll see of Chlothar, this clearly wasn’t great. Radegund managed to extricate herself from this unhappy situation, though, took holy orders, and built a monastery in Poitiers. That institution survives to this day, the Abbey of the Holy Cross. It was heavily damaged during the French Wars of Religion and the Revolution, but a cell and chapel believed to have belonged to Radegund herself were excavated there in 1911.

As for the hapless Hermanfrid, he escaped the battle, and Thiuderic summoned him, giving him safe passage. “Come and talk, we don’t have anything left to fight over! All water under the bridge, hey?” They met at Zülpich, and Thiuderic showered his former enemy with gifts, giving every impression that he wanted to make peace. Gregory’s account of what happened next is very much in keeping with his sardonic, po-faced style. “One day they were seen chatting together on the city walls of Zülpich. Somebody accidentally gave Hermanfrid a push, and he fell to the ground from the top of the wall. He died, but who pushed him we shall never know. Certain people have ventured to suggest that Thiuderic may have had something to do with it.”

Thiuderic? Something to do with it? Oh my tea and biscuits, who could suggest such a terrible thing? Perish the thought!

Childebert and Clotilda

Moving on to our next brother, Childebert.

Childebert was worried about his sister, Clotilda. She had been married to king Amalaric of the Visigoths. The match was arranged by Amalaric’s grandfather Theodoric the Great, in his dance of neighborly matchmaking. The problem was that Clotilda was very pious, like most of the women in our story, you may have noticed, and unlike most of the men, you may also have noticed. When she married the Arian Amalaric, she had been pressured to convert. Clotilda refused. This set her up for continuous abuse at the hands of her husband and his relatives. Gregory is always ready to ascribe the worst behavior to the hated Arians, and according to him Clotilda endured verbal abuse, beatings, and her husband encouraged his people to throw things at her when she made her way to church, including chamber pots and manure. She wrote to Childebert, to whom she seems to have been closest, and complained of her treatment. In one letter she enclosed a rag stained with what she said was her own blood, the results of Amalaric’s mistreatment.

Yair Haklai, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

We’ve heard about what happened then already. Childeric charged down south to make Amalaric pay for his transgressions. Amalaric attempted to flee, but was hampered by the royal treasury. Caught in Narbonne, he was killed. Depending on who you’re reading, he was killed either by his own men or by the Frankish soldiers occupying the city. Childeric collected his sister and as much treasure as he could carry, and headed for home.

Unfortunately, Clotilda died en route back. Gregory does not say how, though there is no suggestion of anything other than natural causes. Childebert had his sister carried to Paris and interred next to their father, Clovis. Gregory makes a note that the treasure collected on this expedition included “a most valuable collection of church plate”, including “sixty chalices, fifteen patens, and twenty gospel bindings, all made of gold and adorned with precious gems.” He notes that these were not broken up, which suggests that that normally would have been the procedure. Instead, Childebert distributed these valuable vestments among the churches and monasteries across his lands. Out of the four, Childebert generally comes off the best out of Clovis’ sons, at least in Gregory’s accounts. Though not perfect, by any means, as we shall soon see.

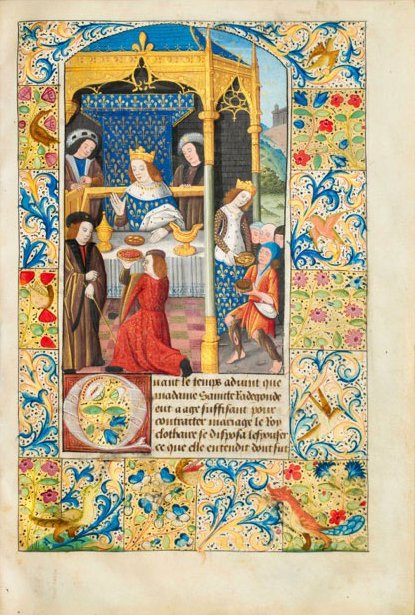

BnF Museum, CC BY-SA 3.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/, via Wikimedia Commons.

Chlodomer and the Burgundians

So, we’ve seen the Thuringians subjected by Thiuderic, and Childebert has reiterated his fathers’ conquest of Aquitaine. The remaining elephant in the room, the rival for control of all of what was once Gaul, was the Burgundians.

The queen mother, Clotilde, had been born a Burgundian princess. Politics had led to the death of her father, and according to some sources, Gregory included, Clotilde harbored resentments against various members of her family, and incited her sons to invade Burgundy and avenge them. It seems unlikely to be honest, and out of character for her. Her sons, as we’ve seen, needed precious little incentive to pick a fight with a neighbor. Regardless, in 523 all four brothers collaborated on an invasion. They defeated the Burgundians and killed their king Sigimund in battle. The Burgundians had been forced to cede lands, and the Franks left garrisons to hold the territory.

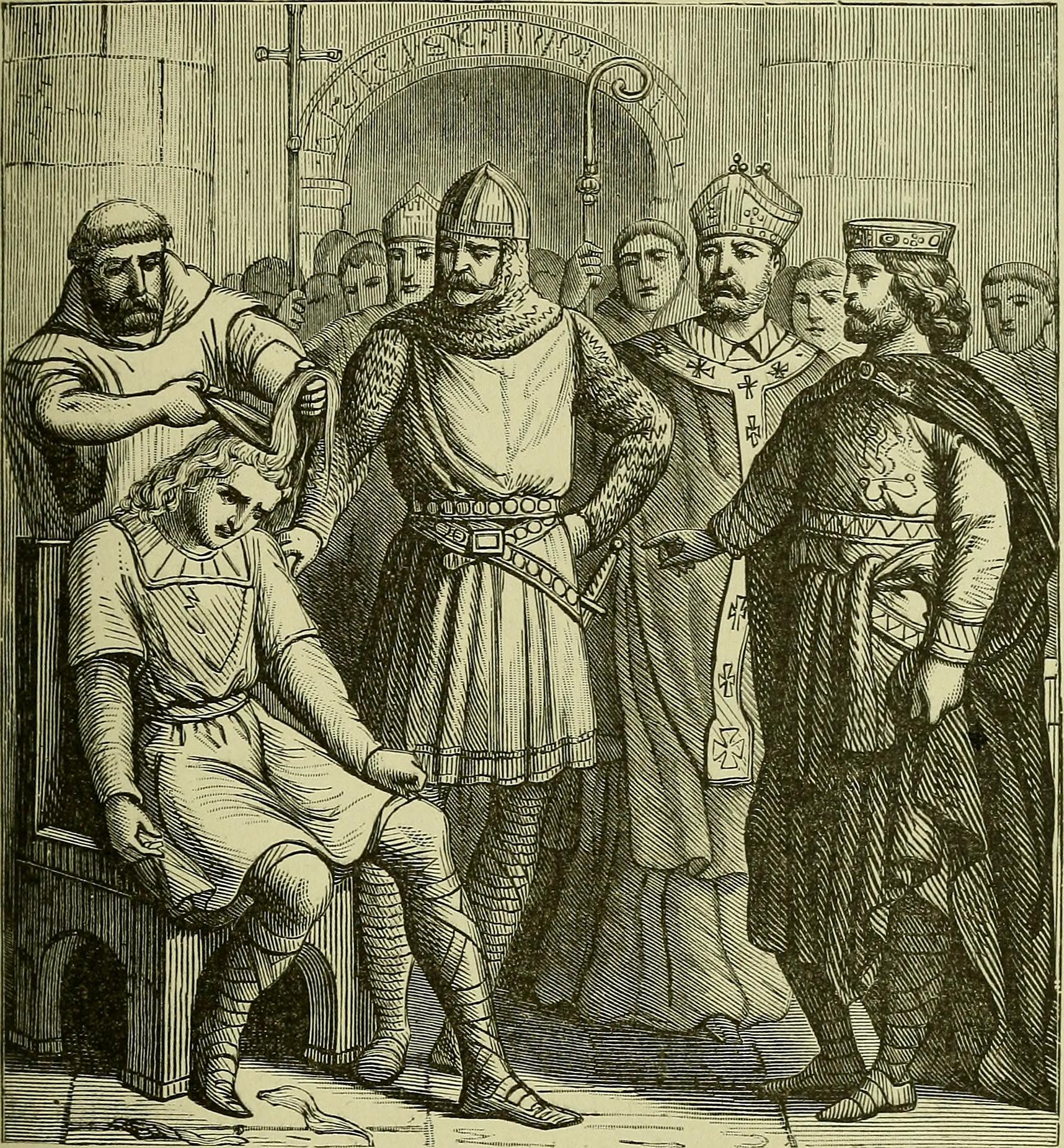

We can guess that Chlodomer is the one throwing the ax, Childeric stands in the dark green tunic, and Chlothar nestles against his mother’s knee. Their half-brother Thiuderic may be the figure in red, looking on.

Lawrence Alma-Tadema, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons, the painting is today in a private collection.

Sigimund was succeeded by his brother, Godomar, who was not the kind of man to just roll over in the face of this kind of adversity. He worked his contacts, and called for help from the southern Giant, Theodoric the Great. With his support, Godomar rallied his forces and attacked, overwhelmed, and massacred the Frankish garrisons.

“An eye for an eye makes the whole world blind” …. was not a saying that the Merovingians were familiar with. Their version would probably have been something like “An eye for an eye is just getting started.”

Chlodomer and Thiuderic, the two eldest sons, put together their response. The plan was to invade Burgundy, finish what they had started, kill Godomar, and take all his stuff. Simple, easy to remember. We went over this quickly back in the oft-referenced episode 37.

Frankish and Burgundian armies met near the small village of Vézeronce. At first it was going well for the Franks, but a moment of confusion altered the course of the battle. Chlodomer, riding across the field, saw a group of young warriors and believed they were Franks, his brother’s men, and rode to join them. The men though were Burgundians, and probably couldn’t believe their luck as the enemy commander delivered himself to them like a Christmas turkey. One of them killed the king, cut off his head and stuck it on a pole. It was then held up and displayed to the Frankish troops. The Franks lost heart, as was often the case when commanders fell, especially so definitively, and retreated.

Honestly, in a time before uniforms or even heraldry was developed, I’m surprised this kind of thing didn’t happen more often.

Godomar and his kingdom were safe for the moment.

Chlothar

Chlodomer left behind a wife named Guntheuc, and three sons, Theodebald, Gunthar, and Clodovald. Guntheuc suddenly found herself exposed by her husband’s misfortune, and married Chlothar, her husband’s youngest brother.

We’ve already seen Chlothar casually picking up a Thuringian princess, who he quickly lost again, and now he seemed to be the best option for Guntheuc for protection.

Chlothar may have been baptized and brought up a Catholic, but he had an eye out for the contradictions of his faith. For example, the bishops for some reason believed that marrying your brother’s widow was icky, and just a little bit too close to incest for their comfort. On the other hand, if Guntheuc came to live with him, she would bring the keys to Chlodomer’s treasury with her. In these kinds of difficult situations, Chlothar managed, after careful thought and consideration to find a path forward – he ignored the bishops and went ahead and married his brother’s widow.

That widow’s three young children would not be accompanying her though. It was decided that Theodebald, Gunthar, and Clodovald would all be sent off to their grandmother Clotilde, to be brought up by her. Clotilde took them in gladly, and showered them with all the attention and affection that a grandmother should.

Here the story takes a dark turn. Childebert and Clothar had second thoughts about the arrangement, and went to their mother to discuss the boys’ futures. These boys were of the sacred House of Merovich, long haired kings in the making. They made the case that it would be better for them to be with their uncles. They could be close to the exercise of royal power, and learn from exposure and experience. Clotilde agreed, and sent them to Paris, where Childebert and Clothar had arranged to meet them.

Childebert and Chlothar were ambitious, lying toads. They had the boys seized and imprisoned instead. The succession was going to be complicated enough without surplus nephews hanging around.

Clotilde’s Choice

The two had worked this out ahead of time, and sent a messenger to Clotilde with a bare sword and a pair of shears. The clear implication being that the boy’s horizons were now very limited, down to just death or tonsure.

The Merovingians are referred to as “the Long Haired Kings” and it was the tradition that long hair was the mark of kingly heritage. Only members of the royal house were allowed to wear their hair long, and only men whose hair was long could rule. Tonsure, besides the religious implication, would remove the boys from any possibility of succession. That seems like a straightforward choice for Clotilde, doesn’t it? Death or a haircut? Apparently not. Pride had its place too Gregory takes up the narrative

“When he [the messenger] came into the queen’s presence, he held them out to her, ‘Your sons … seek your decision, gracious Queen, as to what should be done with the princes. Do you wish them to live with their hair cut short? Or would you prefer to see them killed?’ Clotilde was terrified by what he had said, and very angry indeed … Beside herself with bitter grief and hardly knowing what she was saying in her anguish, she answered: ‘If they are not to ascend the throne, I would rather see them dead than with their hair cut short.’ [The messenger] took no notice of her distress, and he certainly had no wish to see if she would change her mind. Her hurried back to the two kings and said ‘You can finish the job.’”

Murder

So Theodebald and Gunthar were murdered by Chlothar, with his own hands, according to Gregory. The passage is pretty brutal, so here again is your warning to skip ahead if you don’t want to hear it.

“Clothar did not waste a minute. He seized the older boy by the wrist, threw him to the ground, jabbed his dagger into his armpit and murdered him with the utmost savagery. As he died the boy screamed. The younger lad threw himself at Childebert’s feet and gripped him around the knees. ‘Help me, uncle!’ he cried, ‘Lest I perish as my brother has done!’ Tears streamed down Childebert’s face, ‘My dear brother’, he said, ‘I beg you to have pity on him and to grant me his life! I will give you anything you ask for in exchange, if only you will agree not to kill him.’ Chlothar shouted abuse at him, ‘Make him let go!’ he bellowed, ‘or I will kill you instead! It was you who thought of this business! Now you are trying to rat on me!’ When Childebert heard this, he pushed the child away. Chlothar seized him, thrust his dagger in his ribs and murdered him just as he had murdered his brother.”

Theodebald was around ten or twelve, Gunthar somewhere between seven and nine.

Ugh.

Once it was done, Chlothar and Childebert murdered all the boy’s attendants and tutors. The third nephew, Clodovald, escaped, because “those who guarded him were brave men”. Making the seemingly obvious choice, Clodovald cut his own hair and spent the rest of his life as a hermit and later priest. His hermitage, just down the Seine from Paris, became famous and a little town grew up around it. The town was named for him eventually, was the site of a royal hunting lodge, and is known now as St Cloud.

Conclusion

Next time, I’ll continue the narrative, and begin to get a little more disciplined about the chronology, as the final form of the Merovingian kingdom(s) begins to take shape. I apologize for the blizzard of names. I did warn you. There are several Merovingian family trees available online, I will link to a few of them in the show notes and on the website. I think I also will place a glossary of names, a dramatis personae, as a page on the website, and add to it as we go along. Maybe that will help. And maps, of course.

References

Geary, Patrick J. 1988. Before France and Germany: The Creation and Transformation of the Merovingian World. N.p.: Oxford University Press.

Gregory of Tours. 1974. The History of the Franks. Translated by Lewis Thorpe. London: Penguin Books.

James, Edward. 1988. The Franks. N.p.: B. Blackwell.

Wood, Ian N. 1994. The Merovingian Kingdoms, 450-751. N.p.: Longman.