Hello and welcome to this bonus episode of the Dark Ages Podcast: Sandby Borg.

So I know you were all expecting the second part of Brunhilda’s story, but it’s not ready yet, because I’m terrible at managing my time. I think we all knew this already. So instead, let me offer you this bonus episode. Bonus in the sense that it has no relationship to the other episodes around it and won’t be as long as an average episode. It is, in its way, appropriate to an ancient Christmas tradition, because it is a kind of ghost story.

What I want to talk about in this episode is an archaeological site in Sweden called Sandby Borg. Sandby Borg is a ruined fortification dated to the end of the fifth century. It sits on an island overlooking the Baltic Sea, and it is not the largest, oldest, or best preserved fort of the time on said island. What makes Sandby Borg unique is the massacre that took place there.

The remains of at least twenty six individuals have been identified so far, and given that less than 20% of the site has been excavated, the actual number is almost certainly more. All of the bodies show signs of violent, traumatic death. None of them were buried, they were left where they fell. There are children, including one young child between two and five years old, and one infant of maybe two months. The remains skew male – only one adult woman has been firmly identified – but a significant portion of the bones belong to individuals too young to be easily gendered. There are animal remains too, some slaughtered, presumably by the fort’s inhabitants, some killed and left behind, including a few horses, and some which may have starved for lack of human care.

Let me back up and set the scene a bit, shall I?

The island of Öland lies a few miles off the east coast of Sweden, a barrier island, 85 miles long and about ten miles wide at its widest. (That’s 137 by 16 km, for those of you that care.) It’s a decently sized scrap of territory, the second largest island in Sweden, after Gotland, which lies a further 150 miles or so to the East. Öland is fairly sheltered by the mainland, and has been inhabited by humans off and on for 10,000 years.

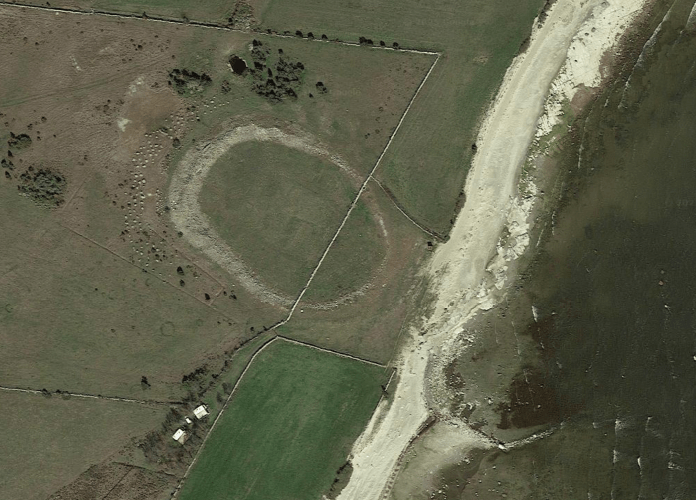

The bit we’re interested in lies about a third of the way up the island’s eastern coast. Sandby Borg is a ringfort, which is exactly what it sounds like. An oval wall encloses an area about 90 meters long and 60 meters wide, roughly the size of an American football field. Today the wall is mostly ruined, standing a meter or two high, but once stood four meters (14 feet) tall, and was about the same in thickness. It was built in dressed local stone on the outer surfaces, with a rubble fill inside. The wall enclosed a tightly clustered group of 53 small buildings, interpreted as houses. Most of these were arranged radially, with the defensive wall forming their back wall, with another block of houses in the middle, forming a street in between with doors opening onto it. Three of the buildings have been fully excavated, with some exploratory digging elsewhere.

I mentioned already that this is not the only ringfort on Öland, fifteen have been identified, and Sandby borg is pretty typical in form. All date to roughly the same time period, the fifth century. The ringfort appears across northern Europe, in Ireland, where they are common, Great Britain, and Scandinavia. Their purpose is still debatable, and they may indeed have had more than one function, and their functions may have differed depending on where they were built. I’ll get back to that in a little bit.

When death overtook the inhabitants of Sandby borg, no one came back to bury the dead. No one came to clean up or reoccupy the site. In effect, time stopped. It’s like a miniature Pompeii in that way, as the remains of daily life are there to be found, catalogued, interpreted, and maybe understood. A collection of lamb bones piled together indicate they had been recently slaughtered and prepared for eating, which places the massacre sometime in the late spring or summer. Rye and mustard seed suggest what may have accompanied the meat. The mustard at Sandby is the earliest example of the herb in Scandinavia.

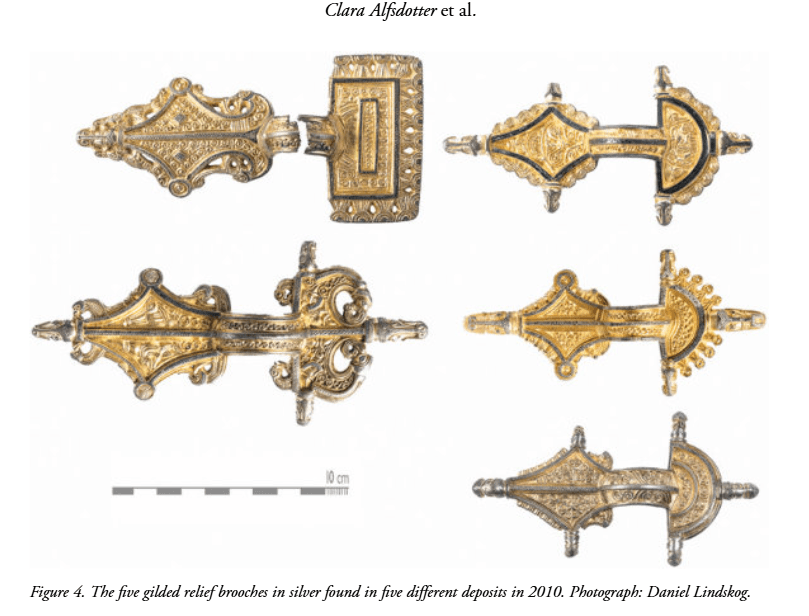

Aside from the people, the archeologists have found a range of artefacts, including a surprising number of what they call “high status items”. Five brooches, intricately shaped in silver and gilded, have been found, along with beads of glass and sliver, ceramics, a sword pendant, just as finely shaped and decorated as the brooches, and a gold solidus of Valentinian III (425 to 455) which helps date the site. Aside from the sword decoration, very little military gear has been found. Signs of clothing, like belt furnishings or clasps, are also largely absent. What there is, like the brooches, was found together with other valued objects, as if hidden in caches. The brooches in particular are gorgeous pieces of metalwork, and I’ll put pictures on instagram. They were probably produced nearby, but other items, especially a large millefiore glass bead, and obviously the coin, were produced inside the Roman empire.

Öland is exceptional in Sweden for the amount of Roman gold that has been found there. More than 360 solidi are known from the island. The distance from the frontiers isn’t surprising, Roman coins are found as far away as Kazakhstan and Sri Lanka. It is their volume and concentration on Öland that may begin to give some idea of what the people of Sandby borg were doing, and maybe what happened to them.

The largest influx of gold appears to have been in the early to middle fifth century, then tailed off rapidly after the significant date of 476. It’s possible that Öland was a jumping-off point for mercenary or raiding bands bound for service or plunder with the Romans. Each could easily become the other, depending on circumstances, and either way, Roman gold would have made its way back to Öland, concentrated as bands arrived, counted their earnings, spent them, and then continued on to wherever home was.

In the context of migration period Sweden, the ring forts may have served as rally points, or hiring centers. With a large number of men with ready cash in one place, they would have also naturally have become nodes of trade. Alternatively, they could have been built primarily as trading centers, designed by local elites to capture and control the flow of goods from across the sea. Many ringforts, especially in Ireland, appear to have been mainly agricultural, the center of a large farmstead, housing the landowner and his immediate family and dependents, along with space for work and livestock.

My opinion counts for nothing, but in the case of Sandby borg, I’m inclined to favor the mercenary/raider idea, for two main reasons. First, the preponderance of males among the dead suggests that this was not a place of permanent residence; the one female and infant may have been servants, slaves, or prisoners, but there seems to be no sign of the complete family structure that you would expect for a permanent farmstead. Second, the number of buildings inside the walls, to me, argues against the agricultural or marketplace idea. There is no space within the fort for a significant amount of livestock, and driving them through the narrow street would have been difficult. Likewise, there seems to be no central market area where people could conveniently gather to trade with each other.

If Öland was indeed an economic center, of trade, mercenaries, raiders, or all three, then there was competition. After 476, the amount of gold flowing out of the west and into the pockets of Scandinavians would have been reduced significantly. The pie would have shrunk, and the competition to grab a piece of it would have intensified in inverse proportion. Put another way, Öland was suddenly full of unemployed fighting men, with no way to make a living. A power struggle over dwindling resources could have fueled the violence that consumed Sandby borg.

The violence there does not in any way suggest a battle. Bodies were found in houses and in the streets. Nine individuals were found in house 40, including the child and the infant. Four of the skulls show signs of blunt force trauma. The same is found in bodies found elsewhere. There is evidence of fire in house 40, either accidental or deliberately set, but it did not spread, and burned itself out fairly quickly. Elsewhere, a man was found partially burned where he fell across a hearth, but again, the fire did not spread, and he was likely dead when he fell. Trauma was mainly from blows aimed at the heads, necks, and shoulders of the victims. Almost no defensive wounds have been identified, as would be expected in a case of active combat.

Under normal circumstances, an assault on a place like Sandby would have been met by defenders who would have been injured in predictable ways; there would be wounds on the forearms, hands, faces. No injuries of the type have been found on these bodies. After the attack, the livestock, the horses in particular, would be rounded up and taken as spoils. Most of the women and children most likely would be spared death and taken instead as slaves. After danger had passed, someone, maybe relatives or neighbors who had escaped the disaster, would have returned, collected the bodies and disposed of them. In the tradition of the time and place, a coin might have been placed in the mouth as a toll to smooth the passage to the afterlife. None of that happened at Sandby borg.

That’s not quite true, actually. Objects were found in the mouths of some, but not coins. In a gesture that shouts across the gulf of time, sheep’s teeth were placed in the mouths of two of the victims. We don’t need to understand the subtleties of the local religion to know that this was a grotesque expression of contempt. It further suggests that the abandonment of the fort was decreed, that neighbors and relations were forbidden to bury the dead or reoccupy the site. And if that is the case, then the perpetrators were most likely local, with the power to enforce such an injunction. Whatever happened at Sandby Borg was, in the words of archeologist Helena Victor, “Really, really ugly treatment.”

The command to avoid Sandby prevailed in the years immediately following the massacre, and then the ugliness took on its own dissuading weight. It would not be outrageous to suggest that the place gained a reputation for bad luck in the generations after the massacre, the way murder houses acquire stories of hauntings today. The taboo against disturbing the ruins may have persisted long after the turf roofs collapsed and the wooden gates rotted away, long after any memory of what exactly had happened there was left. Older locals from nearby Gårdby village remember their parents telling them not to play near the borg, and ghost stories center on the ruins and local churchyard.

Regardless of supernatural echoes, we will never know for sure what happened at Sandby borg. We can guess that a group of fighting men overwhelmed the settlement, perhaps at night. We can see from the skeletons that remain that those inside had little time to defend themselves, and were bludgeoned to death wherever they were found; in the street, in their houses. In one house, a young man stumbled over the body of another, already dead, and fell backwards over him, before being finished off with a blow to the head. His feet still rest across the abdomen of his fallen companion. The attackers killed the horses and left them, and ignored the dogs. Then they left. They barred the gates behind them, leaving the dogs eventually to starve and the bodies to putrefy, until the ones inside were covered by collapsed roofs and the mud swallowed the ones in the street. The fort remained, a silent hulk by the coast, until the memory of what had happened there faded, and the walls crumbled.

The fall of the empire rippled outward, perhaps reaching as far as this corner of Sweden. Warriors, desperate and in need, were pushed into conflict that quickly became savage and led to atrocity. If I may put aside the historian’s detachment for a moment, I hope that the excavations and reconstruction of the lives that were lived and lost at Sandby borg might go some way towards laying their ghosts.

Hope that wasn’t all too grim for you. Part two of Brunhilda will follow before New Year. Until then, god jul. I hope the holidays are as peaceful and full of light as they can be. Until next time, take care of yourselves, and of each other.

References

Alfdotter, Clara, Ludwig Papmel-Dufay, and Helena Victor. 2018. “A moment frozen in time: evidence of a late fifth-century massacre at Sandby borg.” Antiquity 92, no. 362 (April): 421-436. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2018.21.

Curry, Andrew. 2016. “Features – Öland, Sweden. Spring, A.D. 480.” Archaeology Magazine, March/April, 2016. https://archaeology.org/issues/online/collection/sweden-sandbyborg-massacre/.