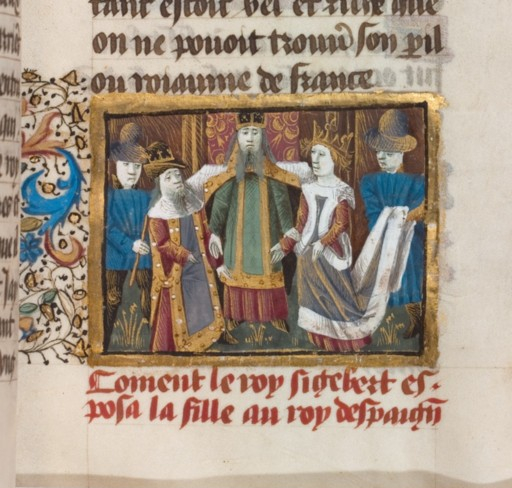

This is part two of the biography of queen Brunhilda, and once again I have underestimated my subject, and overestimated my ability to stay on topic. So it is part two out of three episodes on the life and times of the woman who came to Francia as a Visigothic princess and ended up as regent for three generations of Merovingian kings. In the years that’ll I’ll talk about today, Brunhilda is mainly in the background of our sources. After Sigibert’s murder, she moved to assure her own safety and that of her children, and then to work her way back to the court of her son, the child-king Childebert II. There she gathered a faction and exercised power in the traditional ways of queens. She will emerge as a fully-fledged political power in the next and last installment of her story.

Because Brunhilda is in such an incubation period, there will be plenty of digressions today, aimed at providing some context, both cultural and political, and there will be some names and events that we’ve already talked about cropping up again. Some of that detail that I swore I wasn’t going to go into will be making an appearance today, so those of you that were disappointed about that can get your fix.

But before I start on any of that, the time has come for me to address a geographical situation that I’ve been avoiding up until now.

It is conventional to divide the Frankish empire into four constituent kingdoms within the former Gaulish territories. These are Austrasia, Neustria, Aquitaine, and Burgundy. Territories outside Gaul, such as the Saxon territories beyond the Rhine, are treated separately from these core kingdoms. I have not used these with any regularity, except Aquitaine, because up until now the territorial divisions between the various brothers has been too patchwork for them to actually be descriptive. Now, in the last third of the sixth century, territories are beginning to become more cohesive, and it begins to make sense to use the territorial terms. These names were current at the time – Gregory uses them occasionally – but more often as general regional names, not political entities. Using them as such is more a product of later historians trying to impose some order on all of this stuff. If you look any of these people up today, though, you may see them referred to as, for example, Childebert II, king of Austrasia. They may also be referred to as king of their principal city, Childebert king of Metz, for example, but that really is pushing it. The idea of a single capital isn’t particularly meaningful, and since it’s just another source of confusion for us, I will not be using the city approach.

So for reference, here is my quick description of the four kingdoms of Francia, and keep in mind that a king’s actual territory may include plenty outside the boundaries I describe, which are also all fuzzy and subject to constant shifts.

Starting from the top of the map we find Austrasia. Historians often speak of Austrasia as the Frankish heartland, because it includes the regions of northern Gaul that Clovis and his forebears originally settled. Austrasia is a latin construction that means “East land” and may be a translation of a Frankish name along the lines of “Oster-rike”, so a similar etymology to modern Austria. It spanned the Rhine and stretched west to east roughly from modern Calais into Hesse in Germany, and north to south from the southern provinces of the Netherlands down into the Grand-Est region of France, nearly to Switzerland. Metz was the chief city at the time of Brunhilda’s marriage to Merovech, with Tournai (Tour-nay) and Cologne being other major settlements. Austrasia will be the setting of much of today’s episode, since the young Childebert II was king of Austrasia, with Brunhilda soon to be his regent.

Moving to the west and south, we reach Neustria, or New Lands, presumably because these were the first lands conquered by the Clovis when the Franks broke out of their original territories. Its boundaries are more easily grasped than Austrasia’s, lying as it did between the Somme and the Loire, with the forests of Brittany forming the western frontier, and the forests of the Silva Carbonara the southeastern one. I’ve mentioned the Carbonara before, it was a densely forested region south of modern Brussels, which formed a significant barrier to movement, especially of armies. Paris, Soissons, and Rheims all fall within Neustria’s boundaries, and Tours’ position on the natural border of the Loire meant that it changed hands frequently and gave Gregory plenty to write about.

On the other side of the Loire was Aquitaine, which we are all quite familiar with since it was a Roman province that we’ve talked about a lot. It was prime territory, though not as heavily urbanized in Roman times as other regions. The Franks asserted their control but in general were less likely to settle en masse south of the Loire. As a result, the old Gallo-Roman aristocracy maintained higher status for longer than their northern compatriots, and southern culture developed differently than northern. Aquitaine stretched from the Loire down to the Pyrenees, and from the Atlantic to the Central-Massif and the Auvergne. Bordeaux, Toulouse, and Poitiers were major cities.

Finally in the southeast, Burgundy. Burgundy was much larger than the modern understanding of the region, the most mountainous of the four, and controlled the whole length of the Rhone river. That gave it direct access to the trade routes of the Mediterranean. It also included most of modern Switzerland, Savoy, western parts of Austria and Southern Germany, which had until recently been Alamanni territory. Major cities were Lyon and Geneva.

There is a pretty good map of the Frankish empire at the end of the Merovingian period on wikipedia, and I will also throw it up on the webpage for this episode and instagram. Okay, sorry that turned into a little bit of a slog, but now it’s done and we can get on with the story.

At the end of the last episode, Brunhilda was still in Rouen, having been married to Chilperic’s son Merovech, much to Chilperic’s displeasure. Father and son had ridden away to face a challenging army gathered by the nobles around Brunhilda’s son Childebert. At this point, 577, Brunhilda’s situation seems to have been in flux. Having given up possession of her son to the Austrasian nobility, and now left behind as Merovech left with his father, her freedom of action would appear to have been limited. The truth is that we don’t really know how she returned to Austrasia and rejoined her son’s court, only that she did so. Likewise, what she was doing in the first few years after her return are opaque, as Gregory concerns himself with Merovech’s story instead, as will I.

Chilperic had never really accepted his son’s marriage to Brunhilda, and suspected that the two of them were plotting together to stir up rebellions against him. Whether this was true or not, Gregory does not say, though it does suggest that regular communication between Merovech and Brunhilda was possible and ongoing. Eventually, his suspicions got the better of him, and Chilperic had his son seized, disarmed, and imprisoned. Eventually he had him tonsured, ordained as a priest, and sent to a monastery near Les Mons. Theoretically this solved several problems at once. The ordination and the haircut both served to remove Merovech from the line of royal succession, because a priest could not become king, and because a Merovingian could not be king if shorn of his long hair. It also nullified the marriage to Brunhilda, again theoretically. Merovech had no intention of remaining at his father’s dubious mercy, and looked for a way out, and to make contact with his wife again.

Here I get to reintroduce another character, a dux named Guntram Boso. We met Boso two episodes ago in the affair of Gundovald, which will come up again next episode. Boso was one of Sigibert’s foremost war leaders, and earlier had been at the head of an army that defeated and killed Chilperic’s eldest son, Merovech’s older brother. After Sigibert’s assassination, he had fled to Tours and sought sanctuary from Chilperic’s vengeance. Gregory sheltered him, and turned away the king’s men who came looking, asserting the rights of the church. Shortly afterward, when Boso heard of Merovech’s virtual imprisonment, he sent advice and assistance to the prince, and helped him escape his monastery. Gregory describes the moment when Merovech arrived in his cathedral.

“He was rescued on the road… he covered his face, put on secular clothes, and made his way to the church of Saint Martin. He found the door open and walked in. I was celebrating mass at the time [with Germain of Paris]. After the service was over he asked me for some of the bread of the oblation … we refused, but Merovech made a scene and said we had no right to suspend him from communion … When we had heard him, and with the consent of my brother-bishop he received the bread from my hands, though the case can be argued canonically.”

This seemingly theological question of whether by defying his father and leaving the monastery Merovech had sinned was given practical, and pointed, immediacy, as Gregory went on to explain.

“I was afraid that by refusing to give communion to one man I might cause the death of many, for Merovech threatened to kill some of our congregation if he were not allowed to take communion with us.”

The threat of violence was never far away when there was a Merovingian in the room.

Word of Merovech’s presence in Tours reached Chilperic in short order. Not surprising when the comes of Tours was Chilperic’s representative. The king ordered Gregory to expel the prince from his church or face the consequences. Gregory refused. Chilperic raised an army and started toward Tours. Gregory mentions that Fredegund in particular was eager to catch Merovech, since he stood in the way of her own children’s inheritances. Blood feud meanwhile animated the pursuit of Boso, since it was widely believed that he had killed Merovech’s older brother personally, and mutilated his body after the battle. That Merovech was working so closely with the supposed killer of his brother suggests both how desperate he was, and is just one more example among many of the strange bedfellows that politics can make.

If we take Gregory at face value, Fredegund was secretly a Boso fan, since he had eliminated one of her hated stepsons for her. She secretly sent word to Boso, promising rewards if he could manipulate Merovech out of hiding. Boso tried, but to no avail.

Finally Merovech decided he was getting nowhere by hiding out in Tours, and rode out. He made it to Auxerre, where he was briefly captured, but escaped. Meanwhile, Chilperic laid waste to the countryside around Tours, to Gregory’s distress.

Finally Merovech attempted to rejoin Brunhilda, but, “the Eastern Franks would not receive him” and he was forced back on the lam. He drops from sight for a while.

I hadn’t really intended to go over this story again in so much detail, but might as well finish it.

Unable to trust the Austrasian Franks, Merovech was hiding somewhere near Rheims, along with some remaining loyal followers. The leaders of a town called Therouanne – later to be destroyed by Henry VIII, offered to rebel against Chilperic if he would lead them. Merovech jumped at this seemingly miraculous offer. But it was a trap. As soon as Merovech arrived, the estate he was staying in was surrounded, and word sent to Chilperic, who dropped everything to deal with his defiant son. Merovech knew he was caught, and fearing capture and torture, asked a servant to kill him with his own sword, which he did. Merovech’s servants and remaining followers were captured, many tortured, and executed.

We don’t know how old Merovech was when he died in the year 577, but since his father was not yet forty and Merovech was his second son, he was probably just barely on the far side of twenty, if that. And just like that, at the age of probably 33 or 34, Brunhilda was a widow for the second time.

And what had she been doing all this time, while her young husband scurried from one rat hole to the next all over Northern Francia?

She had been mainly in the Austrasian capital in Metz. Presumably she had been shoring up her own position, wielding that influence that we talked about last time. As queen mother it would have been in her power to grant household positions that could be quite lucrative, and must have worked the connections she already had from before Sigibert’s death. It would have been a period of quiet conversations in corners. A time for her to hold her ear to the ground and learn who around her son she could trust, who she should fear, who might be susceptible to bribery, or flattery, and who might one day need to be dealt with more firmly. Alas, we cannot know the specifics. We can only be sure that she either was not powerful enough to intervene on Merovech’s behalf with the “eastern Franks”, or for reasons of her own, she did not want to.

In the absence of direct information about Brunhilda’s activities, we can turn to Fredegund. In 579, Chilperic levied new taxes on the landowners of his territories, which according to Gregory were onerous beyond reason. A whole gallon of wine was owed for every half-acre of land, which is apparently a lot, and there were further taxes on movable property and employees. It was already a bad year in Frankish territories. Floods hit the Auvergne, the Loire, and the Rhone. An earthquake struck Bordeaux and its hinterlands, followed by widespread fires. The ancient city of Bourges was damaged by severe hail.

All of these were simply harbingers of worse to come. An epidemic swept through the populace, with fever, vomiting, and, for many, death. It struck the young hardest of all. Here Gregory gives us one of many pieces of evidence counter to the idea that ancient and medieval people loved their children less than we do. “And so we lost our little ones, who were so dear to us and sweet, whom we had cherished in our bosoms and dandled in our arms, whom we had fed and nourished with such loving care. As I write I wipe away my tears and I repeat once more the words of Job the blessed, ‘The Lord has given, and the Lord has taken away.’” It’s one of the most attractive of Gregory’s personal qualities that come through in his writing, his obvious concern and affection for the children of his diocese, even though he had none of his own.

The epidemic, as is their nature, made no distinctions between high and low, and it struck at Chilperic’s family too. Chilperic himself fell ill, but recovered. However, his two youngest children, his sons with Fredegund, were severely affected. Fredegund panicked, had the tax records for her own cities burned and urged her husband to do the same. “What are you waiting for? Do what you see me doing! We may still lose our children, but at least we will escape eternal damnation!” Chilperic agreed, had the tax registers brought from around his kingdom, and destroyed them. But Fredegund was right, the two youngsters died shortly thereafter. Fredegund’s scheming to ensure they would be their father’s only heirs had come to nothing.

Hostile to Chilperic though Gregory is, he was able to concede that after this tragedy, the king became much more generous and gave lavishly to churches and monastery, as well as direct alms to the poor. Chilperic had lost at least four children by this point, and I can only imagine that that might make one pause. In contrast, Gregory offers the example of king Guntram’s queen, who died of the same disease, and in rage at her fate, made her husband swear to take vengeance on the doctors who failed to save her. Forced by honor to complete his vow, he had two of her physicians executed immediately following the funeral.

Besides the wide variety of human reactions to mortality, there is another point I want to draw out from Fredegund’s story, and that’s the existence of tax registers. It speaks to a level of praxis and record keeping that doesn’t jibe with the image that immediately forms in our heads when thinking of early medieval government. I’ve said plenty of times that in my use of the phrase “Dark Ages” I’m thinking of the absence of historical documentation for the period, but just because documents have not survived to our own day does not mean they were not created. While it would have been nowhere near the volume produced by the Roman bureaucracy, the Frankish kingdoms would have generated significant quantities of administrative paper work (not paper, but you know what I mean). It’s just no one thought to save any of them, which was inconsiderate of future historians, but understandable.

Within a year or two of these tragedies, Brunhilda finally comes back into view, exercising power among and upon the nobles of Austrasia. Two of them, named Ursio and Berthefried, were engaged in a running feud with another, named Lupus. Lupus was dux of Champagne, a wealthy and influential man, and one of Brunhilda’s supporters. Berthefried and Ursio conspired to have Lupus killed, formed an alliance to that end, and sent an army into his territory. They were probably hoping to bring him to open battle, where he could be targeted and killed. How big these forces were is unknown, they probably were simple raiding parties of a few hundred at most. Not that it mattered; a disturbance of the peace like this was exactly the kind of thing that royal power was supposed to keep a lid on. Brunhilda acted, and Gregory’s recounting is full of admiration:

“With a vigour that would have become a man she rose in her wrath and took her stand between the two enemy forces. ‘Stop!’ she shouted, ‘Warriors, I command you to stop this wicked behavior! Stop harassing this person who has done you no harm! Stop fighting each other and bringing disaster upon our country, just because of this one man!’ ‘Stand back woman!’ Answered Ursio, ‘It should have been enough that you held regal power when your husband was alive. Now your son is on the throne, and his kingdom is under our control, not yours. Stand back, I say, or you will be trodden down into the ground by our horses’ hooves!’ For some time they shouted at each other, but in the end the queen prevailed and stopped the conflict.”

Combat was averted, but the conflict remained, Brunhilda was not powerful enough to put an end to the feud for good. After departing the battlefield, Ursio and friends still raided at least one of Lupus’ estates and carried off valuables. What we have here is an Austrasian court split into two factions, let’s call them the royals and the nobles. The royals were those who supported young Childebert II and Brunhilda as his regent. The noble faction meanwhile strove mainly to keep royal power from interfering too much in their own affairs and activities, and to oppose any initiatives that might decrease their freedom of action. Resolution was unlikely without an adult king, as many of the noble faction would be patently unwilling to take Brunhilda’s authority seriously. Recognizing that he would not be safe in Austrasia at least until Childebert came of age, Lupus went into voluntary exile in Burgundy with king Guntram, to wait for conditions to improve.

Shortly afterwards, Childebert and Brunhilda were forced to follow Lupus to Guntram’s court, where they took refuge from potential assassins and prepared their next move. Guntram proved key to the success of Brunhilda and the royalists; he had no natural heirs, and in 587 Brunhilda convinced him to adopt Childebert, in an agreement called the Pact of Andelot. Guntram provided support for the Royalists to return to Austrasia and subdue the nobles, and would continue to support the regime until his death in 592. The royalist return was violent, Ursio and Berthefried, who had made so much trouble, were driven out of their fortress and killed, and the nobility were, shall we say, realigned. According to Gregory, “At this time a great number of men emigrated to other regions, for they were greatly afraid of the king. Certain dukes were demoted from their dukedoms, and others were promoted to replace them”. He names the king, but given that Childebert was still underage, we have to assume that most of the impetus for this comeback originated with Brunhilda.

Now on much firmer footing, Brunhilda was unquestionably the regnant power in Austrasia. She pushed administrative reforms and insisted on royal rights, many of which had been eroded by noble intransigence. She also distributed patronage by endowing abbeys and churches, and worked to rebuild and refurbish the old Roman road system.

Brunhilda carried on making dynastic arrangements as well. Specifically, she arranged the marriage of her daughter, Ingund, to the Visigothic prince Hermanigild. I told their story already, in episode 52, A Saintly Prince, almost exactly a year ago. Their marriage in 579 was a diplomatic success for Brunhilda, but as she sent her thirteen-year-old off to retrace the steps that she herself had taken when she came to Francia, Brunhilda would have known she would likely never see her again. So it proved, as Ingund and her husband died just six years later, following his Catholic conversion and subsequent rebellion.

Arrangements for Brunhilda’s other daughter, Chlodosinda, were less successful. She was initially betrothed to the king of the Lombards, who was attempting to outmaneuver the Byzantines with a Frankish alliance, but the vagaries of diplomacy kept the deal from being finalized. She was then to marry Reccared, the king of the Visigoths, but again, the marriage fell through. This time it was nixed by Guntram, who was not a fan of the new Visigoth king, at least in that moment.

What ultimately happened to Chlodosinda is not explicitly mentioned in any surviving source; she may have stayed closer to home and married a Burgundian noble, but it’s unclear.

Alongside the building of parties and the arrangement of marriages, Brunhilda also played a traditional queens role as a patroness of culture. That gives me an excuse for one more digression, and one that will go a long way to explain how profoundly things had changed in the century since the last gasps of empire in the west. The fall of the empire must be understood as a political collapse, first and foremost; a system that stopped working. It was not a social collapse, at least in the short term, nor was it a cultural one. Not on the continent at least, Britain is a different story. I’ve banged on and on about how the Roman elite landowning classes largely stayed in place across the old imperial territories, and how the successor kingdoms were the result of deals negotiated between them and the new warrior elites. There was some violence, certainly, some elite families saw their fortunes reduced as the barbarians inserted themselves into the system, but in most of the western provinces, the landowning classes were still made up of the original Gallo-, Hispano-, or Italo-Roman families that had been in place before. Social and cultural changes followed, working themselves out over the next few generations.

Culture was changed by the political realignment in a deep and fascinating way, but to explain it, I’ll need to go back a bit to talk about the governmental structure of the late Empire. I’ll keep it as brief as I can, but it is interesting, I promise.

In the last century of empire, the size of the imperial bureaucracy had increased dramatically, as budgetary authority shifted from town councils to more centralized control. The shift was driven by the need to fund the various civil wars of the period. The need to administer a new and extremely granular land tax system meant that a small army of administrators fanned out across the empire to assess property values and collect dues. The effect of this expansion had an important effect on the behavior of the local landowning elite. Rather than seek status and advantage by serving on city councils, as had been the previous approach, young men of the upper classes sought posts in the imperial apparatus. For one thing, knowing someone in the tax office could go a long way toward reducing your family’s overall bill, not to mention the potential for lucrative kickbacks, and a chance to hamstring your local rivals. Competition for these posts was intense, and education was the gateway to success.

The educational system revolved around a cadre of specialists, known as grammarians, who taught an intensive curriculum in Classical Latin language, using a canon of texts that had remained largely unchanged since the first and second centuries. Christianization had contributed a few texts, but the Roman aristocrat’s attachment to Cicero, Virgil, and company was too strong to be dislodged by the shift in religion. As a result, the upper crust spoke an ossified version of latin that was distinct from the vernacular dialects that were already evolving into Early romance languages. The use of “Proper” Latin marked them out as members of the upper class, suitable for imperial service. The education was further refined by the next level of education, provided by rhetors, who taught rhetoric and forms of complex textual analysis, which were vital to understanding and functioning within the legal system. (Saint Augustine worked as a rhetor for part of his pre-conversion career.) The same analysis, applied to biblical texts, would be a large part of the intellectual working out of Christian doctrine, but that’s another story.

My point for now is that high-level skill in latin, both prose and poetry, were essential markers that were required for entry into those imperial jobs. The same system was in place in the east, though the language of choice there was Greek, not Latin. That alone kept the grammarians and rhetors busy and well employed in the later years of empire. It meant a high level of literacy among the landowning elites of the provinces, because that was how you got ahead. Those elites also took over the top church posts, once Constantine and his successors made it clear that the bishops would be a part of the governmental framework as well.

You can probably see where this is going.

When the governmental structure crumbled, most of those jobs disappeared. Taxes still needed to be collected, but the smaller successor kingdoms didn’t have the resources to maintain the bureaucracy on the same scale, and had different needs. What kings of the Franks, Visigoths, Burgundians needed more than civilian administrators was fighting men, and that was who they rewarded with jobs and favor. A firm command of Latin was replaced by a firm understanding of sword and shield as prerequisites for advancement, and the elites adjusted their priorities accordingly. Christianity, always a religion of the Book, still required literate leaders, but the church could not hope to replace the government as a large-scale employer. At the end of the fourth century there had probably been around 3,000 top-level jobs in imperial service in the West outside of Africa, along with innumerable support staff that required an elite education. Compare that to the 350 or so bishops in the same area after 476, and the reduction in demand for grammarians and rhetors becomes obvious. The church eventually would take over education from the independent teachers and so ensure its own supply of staff, but the number of landowners that were receiving training in latin and high level literacy was reduced dramatically. It is likely that the kings and magnates of Francia could read enough to manage their estates, but most writing was done by scribes, and complex literary writing and analysis was now limited a handful of high-level churchmen. The teaching of Greek, never as prevalent in the west, pretty much vanished completely.

However! None of that meant that the cultural legacy of Romanitas had ceased to be valued. Latin poets and prose writers found patronage at the courts of the Merovingians, as well as in Italy and Spain. Rulers were happy to support anyone who could sing their praises in well-constructed Latin, it’s just that there were fewer opportunities for such men available.

The epitome of this class of poet was an Italo-Roman named Venantius Fortunatus, born sometime around 530, he made his bones writing praise poems and hymns for the royal courts and churches of the Merovingians. Some of his work survives as parts of modern Catholic and Anglican liturgy, but his earliest known work was a panegyric written to celebrate the marriage of Sigibert and Brunhilda. See? I told you we’d get back to her eventually. From that speech:

Sipping flowers and charming with delicate humming,

bees hide away in combs their delicious honey.

Fecund in providing progeny with a pure marriage bed,

one desires a flower to bring forth masterful children.

Ready by obligations with love for posterity,

the twittering bird hurries, hastening toward children.

With offspring each, although old, becomes young in them.

When all thus reappear, the world has joy.

Besides the fact that this reference to birds and bees predates Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s supposed invention of the metaphor by 1200 years, the poem is a little chunk of the old order, valued and supported by Sigibert and Brunhilda, and by the whole Merovingian family. Fortunatus would write for most of the Frankish royal courts, as well as a life of St Martin for Gregory of Tours. The highest point of his career would be as a hymn writer for Queen-Abbess Radegund, and he would eventually be appointed Bishop of Poitiers, and died sometime early in the seventh century.

With her sponsorship of Fortunatus, as well as other poets, Brunhilda carried on the respect for romanitas as a cultural ideology, even as the political landscape had changed out of all recognition since the days of empire. Maybe her upbringing in the more romanized Visigothic courts had predisposed her to appreciate well made latin verse, who knows, but there were plenty of others within Francia that shared the appreciation. In spite of the constant infighting and family drama, Francia was now without question the most powerful, richest, and most influential of the western kingdoms, and its influence was felt by all its neighbors, culturally as well as politically. It will be an ongoing thread through pretty much all the stories I tell for the foreseeable future.

As for Brunhilda, her regency would end officially when Childebert attained his majority, but she remained an influential figure at his court. She may have thought that, having guided her son to his rightful place, she would live out the rest of her life as one of the voices advising him, but fortune turned her wheel, and she would find herself once again at the center of events

Which we will talk about next time.

I’m releasing this episode on New Year’s Eve, 2025, because I promised I would have it out before the new year. My resolution is to continue to be much more diligent about this rickety old show of mine. It’s the least I can do for all the support you all have given me, both financial, for which I’m always grateful, and moral, with your comments and reviews and emails. I hope that the new year brings you all the blessings that you have earned and none of the troubles that might trip you, may the sun be ever on your faces and the wind at your backs. I’ll see you all next year, until then, take care.