Brunhilda Part 3

584 to 612

This is part three of a two-part episode on the life and times of Queen Brunhilda of Austrasia, and as you can probably guess from that introduction, things are not going entirely to plan. I absolutely refuse to let this story extend itself into four parts though, so this episode is going to take as long as it takes, word counts and time targets be damned. It has ended up being the second longest episode so far, in terms of word counts, in fact. You have been warned. It will cover the second half or so of Brunhilda’s life, when she really hits her stride as a political animal, and it’s got to be said, does not conduct herself in a way that would earn the approval of most modern observers. Actually it didn’t earn the approval of her contemporary observers either, and I’m just going to spoil it now: she came to a bad end.

Before that, I need to start with a correction from last time, actually, namely regarding chronology. The thing about these-here Early Middle Ages is that nobody really has their calendars nailed down, and while deaths of kings and saints are usually recorded with some precision, birthdays very seldom are. Combine that with me rushing a little bit and being careless, and we end up here, with me apologizing.

Last time, we left off with Bruhilda and Childebert returning from a period of exile, forced on them by the Austrasian nobility. They had fled to Guntram, Childebert’s uncle and king of Burgundy, seeking protection and support. He had agreed, and the three had reached an agreement called the treaty of Andelot. With that support, Childebert had returned to Austrasia, reclaimed his position, and driven out the nobles and magnates that had opposed him, with some brutality.

Now here comes the correction: last time, I said that the treaty had been completed while Childebert was a minor, and that therefore the following purge could be laid mostly at Brunhilda’s feet, I was mistaken. I apologize, for I got tangled in the web of conflicting sources and chroniclers. The truth is that at the time that Guntram, king of Burgundy took Childebert and Brunhilda under his protection, the king was probably around seventeen years old. Now, I know only a handful of seventeen year olds who I would trust with the management of a Carl’s Junior, but at the time, he would have been considered fully ready to take over management of his kingdom as an equal to the other Merovingian kings. In a way that only serves to highlight Brunhilda’s position, since she is named there as a party to the treaty, right alongside her adult and legally competent son. I still assume that Childebert’s ferocious return to Austrasia was to a significant degree directed by Bruhilda, since she would have been the main voice educating the king about the politics back home, who to trust, and who to mullah.

There is a second chronological boo-boo to clear up, namely, the death of Chilperic, uncle of Childebert, and husband of Brunhilda’s arch-rival Fredegund. Chilperic was assassinated in 584, which is before Bruhilda and Childebert were forced out of Austrasia, not after. He was stabbed by parties unknown while dismounting from his horse after a hunting expedition. I have not been especially sympathetic to Chilperic in these pages, generally painting him as jealous and petty, with a chip on his shoulder. In that I have largely been following the lead of Gregory of Tours, who did not like him one little bit. I’m not going to say that Gregory or I have been unfair, except to say that it’s likely that he was not as bad as depicted, just as his opponents, as we shall see, were not as good as they have so far been depicted. Chilperic was around 45 when he died, and had been king of Neustria for 23 years.

He had produced eleven children over his life, five with his first wife Audoveda and a further six with his true partner Fredegund. Nonetheless, at the time of his death, only two legitimate offspring remained, a daughter named Rigunth, about 14 when he died and who had, shall we say, a complicated relationship with her mother, and the infant Chlothar, only four months old when Chilperic met his maker. Fredegund found herself in much the same position that Brunhilda had been in when Sigibert died, but quickly secured her position as regent. The nobles who had been loyal to Chilperic swore to continue to support his son, and Fredegund even prevailed upon Guntram to extend his protection, which may have made things awkward between Guntram and Brunhilda for a while.

Now once again I have reason to revisit the Gundovald affair, mainly because it is one of the few incidents of intrigue where we have anything like a complete narrative, and so it’s a well to which historians are forced to go again and again when piecing together the story of the Merovingians. I need to tie it to Brunhilda, and see what it tells us about her. My chronological incompetence appears one more time, since the appearance of Gundovald and his claim to Frankish kingship came before, or just around the same time, as Bruhilda and Childebert’s expulsion from Austrasia, and may have been related to it.

To quickly recap, Gundovald was a pretender who claimed to be a son of Chlothar the first. Chlothar refused to recognize his right to rule, and he spent some time in exile in Italy. Once Chilperic died and there seemed to be an opening, he returned to Francia and claimed the loyalty of several cities, mainly in the south. He arrived suspiciously well funded, and many of the nobles who should have responded to kick this threat to their kings’ power out were suspiciously slow in doing so.

The Gundovald affair seems to have been a raw nerve when Gregory was writing, with the suggestion that he was less than forthcoming with details because it was not safe for him to write candidly. That suggests that there were still nobles who had been involved with the failed plot, and were in a position to make Gregory’s life difficult. Is it possible that Brunhilda was one of them? At first it seems ridiculous, the noble faction that supported Gundovald’s takeover attempt seem mainly to be the same one that opposed Brunhilda’s influence with the king. It’s hard to see what she would have gained from introducing a new destabilizing element to the Francian formula. Nothing in Gregory’s narrative is suggestive, but we’ve already seen one reason why he might keep stum, and furthermore, some lines in a work by Fortunatus suggest that Gregory may have owed his appointment as bishop to Brunhilda’s influence. That makes his generally rosy picture of the queen much easier to fathom, and to distrust.

Given that rosy picture then, we need to turn to the equally biased account of Fredregar, a chronicle that I’ve generally dismissed up until now, but now that we are reaching the end of Gregory’s narrative, the only other comprehensive source we have for the time. Fredregar is biased in the opposite direction from Gregory, and I’ll talk more about that in a little bit, but let’s just take a look at what he says about Brunhilda and the Gundovald situation. After Gundovald had arrived in Francia, it became clear that Childebert and Guntram were of one mind; they would not recognize the newcomer’s rights, and swore together to oppose him. Many Burgundian nobles attended the same meeting and swore the same oath, but very few Austrasians were present, which Guntram found suspicious. He warned Childebert not to trust his mother, and at the same time seems to have recognized that Childebert had reached his majority and should have control of the cities that his father had held. Shortly afterward, Gundovald took over the fortress at Comminges, and Guntram sent him a letter, claiming to be Brunhilda. In those days when letters were pretty much all dictated to scribes, forgery was fairly straightforward. He gave Gundovald all kinds of terrible advice in the name of the queen, and so set Gundovald up for his eventual defeat and death.

That all seems pretty damning, but the question remains: why? Why would Brunhilda support a usurper who might threaten the good order of the Frankish kingdoms? Well, as in so much of life, timing is important. It’s pretty clear, now that I’ve read all this more carefully (cough cough) , that the Gundovald affair kicked off after Chilperic’s death and before the noble revolt that drove Brunhilda from the Austrasian court. In other words, after Guntram took Fredegund and Chlothar under his protection, and before he did the same for Childebert and Brunhilda. Gundovald’s claims were mainly focused in territories controlled by Guntram. If we take Fredregar at face value, here’s my thinking: and it is mainly my thinking, which you should take for what it’s worth: the thinking of an amateur in his basement, who in spite of his pretensions, can’t even read the latin sources reliably (not for lack of trying). Okay?

Okay, so here’s my thinking. Chilperic dies, and Fredegund turns to Guntram for support and protection. Brunhilda learns of this and worries about a shift in the balance of power, with Guntram and Fredegund now threatening her and her son. In fact, Guntram and Fredegund’s alliance was never easy or strong, but Brunhilda wouldn’t know that yet at the time, and she panics. She’s in a strong but not unassailable position in Austrasia, and feels the need to pull more of the nobility into her circle. Meanwhile, the death of Chilperic has opened up those cracks among the nobility that we’ve talked about before, making spaces for pretenders to insert themselves. Maybe Brunhilda knew about Gundovald beforehand, maybe she heard of him from some other source, like Boso, who met him in Constantinople. In her rush to counter the move by Fredegund, maybe she aligned herself with the noble faction that had previously opposed her, and supported Gundovald, either morally or materially.

If that’s the case, it would appear that Childebert was either unaware of his mother’s activities, or opposed them. I lean toward the former, if the meeting between Guntram and Childebert is accurately reported. If that is the case, then Guntram was engaged in some pretty high-level politics of his own. He must have known that Brunhilda would not take his protection of Fredegund well. In this reading, by recognizing Childebert’s majority, Guntram was setting him up as the actual, rather than just potential head of government, and creating a new center of authority within Austrasia that Brunhilda will have to deal with. Sowing further division by advising the young king not to trust his mother, the old king was just as much an operator as she was. And he was, obviously, good at it. As I say, that’s largely speculation, but I’m enjoying this, so let’s keep it going and see what else we can shake out.

If this scheming on behalf of Gundovald wasn’t the only incident that led to Brunhilda being sent away from the Austrasian court, it almost certainly was on the list. Gundovald’s failure would have discredited anyone who had supported him. Suddenly, purveyors of ass-covers would have found themselves in a sellers’ market at the Austrasian court. Since they were not fans of Brunhilda to begin with, it would have made sense for her to be made a scapegoat for the whole thing, possibly with Childebert turned against her. Indeed, it’s hard to imagine how she could be forced out without the king’s approval, or at least his turning of a blind eye. Uncomfortable though it may have been, there would have been no option for her but to seek refuge with Guntram; going to Neustria and Fredegund would have been literal suicide.

Who knows what she said to Guntram, or what he said to her, when she appeared at his court in Orleans, it must have been agony for the proud lady.

Okay, you’re all thinking, but last time you said that Childebert was with the queen when she fled to Orleans… and yes I did, but they may not necessarily have arrived at the same time. My guess would be that in his mother’s absence, Childebert found himself unable to cope with the Austrasian nobility. She had the knowledge, the contacts, the leverage, and without her, Childebert was quickly overwhelmed by an emboldened elite. They most likely expected a puppet, and rather than knuckle under, he left, sought help from mom and uncle Guntram, and the three of them managed to find a way to work together, formalized in the treaty of Andelot. It probably helped that somewhere in there, Fredegund attempted to assassinate Guntram, but failed, which will often sour a friendship.

Against the run of play, the Guntram-Brunhilda-Childebert axis would turn out to be a strong relationship. Guntram would refer to Childebert as his son, his own sons having died of illness in 577. He also confirmed that Burgundy would pass to Childebert when he died. It wasn’t perfect, there was an incident a few years later when Guntram accused his nephew of failing to abide by the treaty, but they worked it out in the end.

Guntram died in 592, and as agreed, his Burgundian lands passed to Childebert. He was about sixty when he died, the elder statesman of Francia, and had been king of Burgundy for 29 years. I haven’t done him justice. He was the most uniformly praised of Chlothar I’s children, he was wild in his youth, but saw the light later and worked hard to be a good king. Overall he comes across as a reasonable man and clever politician. There was that incident with the execution of his wife’s doctors, but it doesn’t really stand out on the list of Merovingian brutalities, he was reluctant to do it, and regretted it afterwards. Gregory seems to have enjoyed his company on a personal level, and was comfortable joking with the king. He relates a dinner he shared with Guntram, where the king asked, “Tell me, is it really true that you have established warm friendly relations between my sister Brunhilda and that enemy of God and man, Fredegund?” Gregory said: “The king need not question that the ‘Friendly relations’ that have been fostered between them are still being fostered by them both. That is to say, you may be sure that the hatred which they have borne for many a long year … is still as strong as ever.” I enjoy imagining the long-haired king choking on his wine and pounding the table at Gregory’s quip, a reaction I struggle to imagine from Chilperic, or from Brunhilda, for that matter. Praise of Guntram is one of the few things that Gregory and Fredregar agree on, the latter eulogizing him: “he passed on, as seems likely, to the eternal realm, for he had always behaved well, in good conscience, and had given alms liberally… he was generous towards prelates, humble and mild towards the ministers of holy church, a man of good will towards his own people, and gentle towards foreigners. Because he shone with such virtues, many foreign nations magnified his name and his praise.” Guntram was so popular with his own people that he was almost immediately venerated as a saint, and the church of Saint Marcellus in Chalon, which he founded, preserves his skull to this day.

That was a bit of a digression, but I felt that the old man deserved a send off.

The inheritance of Burgundy expanded Childebert’s power massively, and Brunhilda’s with it. There’s little evidence of any further serious strife between the two. I’d imagine that the experience of shared exile and the perfidy of the Austrasians would go a long way to convince both of the importance of their relationship. That doesn’t mean that Brunhilda didn’t continue to manipulate and manage her relationships and those around Childebert, she did, but she was never again in the same kind of danger, as long as her son lived. Subtle foreshadowing there.

We’re between chroniclers during the 590s, and the period is generally poorly recorded. So we have even less detail about the goings on in the now combined court of Austrasia and Burgundy.

What we do know is that the animosity between Fredegund and Brunhilda had not abated even a little bit. The blood feud begun with the murder of Galswitha had been given even greater force by the murder of Sigibert, and now Childebert prepared to use his newly enhanced power to punish Fredegund for both. He gathered an army and made ready to invade westward. Fredegund apparently had a strong intelligence network, and had ample warning of Childebert’s plan, and rallied her own forces. Supposedly she addressed the assembled Neustrian barons while breastfeeding the infant King Chlothar, which the chronology doesn’t really support, since Chlothar would have probably been too old, but it’s a nice dramatic image. Either way, she accompanied and led the army response, though without actually fighting.

The Neustrian’s quick response caught Childebert by surprise. They found the Austrasians in camp, utterly unprepared. The attack was quick and decisive, the camp was plundered, many were killed or captured, and just for good measure the Neustrians went on to pillage broad swathes of Champagne. Chlothar held on to his kingdom, thanks to the tenacity of his mother, and the score in the bloodfeud match remained firmly in Fredegund’s favor.

The defeat wasn’t crippling though, since Childebert was perfectly capable of raising armies for other purposes. Childebert acquired a reputation as a war leader, along with several of the magnates around him, and Austrasia was a power with genuinely international reach. Pope Gregory wrote to both King and Kings’ mother on various matters, and Childebert campaigned both at home and abroad regularly. There was a rebellion to put down in the Auvergne, and most notably a campaign against the Lombards, undertaken at the request of the Byzantine emperor Maurice. That one involved the levies of more than twenty barons and magnates, and was initially very successful. The Franks captured fortresses and towns across Northern Italy, reaching as far as Trento, when they were forced to turn back by an outbreak of disease.

Brunhilda obviously had little to do with military expeditions abroad, but her hand remained on the tiller of state, both domestically and abroad. Her daughter Ingund, having been driven from the Visigothic kingdom after her husband’s rebellion (see episode 52: A Saintly Prince), was languishing in Africa in diplomatic limbo. Brunhilda wrote multiple letters to the emperor seeking aid for her daughter, but to no avail. Ingund died in Carthage in 584, probably of plague. Her standing seems to have been equal to that of the king on the diplomatic stage, judging by the tone of surviving correspondence.

At home, Brunhilda kept a close eye on the people who surrounded the king. I’m sure she would argue that this was to his benefit, but his benefit and her position were closely aligned in her mind. The clearest example was in the king’s love life. Clearly the king needed an heir, that was obvious. But that obvious need did not sit comfortably with Brunhilda’s desire to maintain her influence over her son. Any woman he took as his queen would immediately become a rival for his attention, especially if she was noble with strong connections. Fredregar alludes to Brunhilda scotching at least one proposed marriage to the daughter of a Frankish magnate, though details, as usual, are lacking. Suddenly and mysteriously, a son appears in the chronicle, born 585 or so and named Theudebert, with no wife or consort mentioned. A wife for Childebert is not mentioned at all until 587. She is a woman named Faileuba, and there is simply no information about her background at all. She’s essentially a non-entity, either a Frankish woman without strong connections at court, or possibly a Visigothic princess, which, as Brunhilda would know from personal experience, placed her kin too far away to have any practical effect on Frankish politics. A second son was born to Childebert and Faileuba in that same year 587, named Thiuderic. It’s often assumed that Faileuba and Childebert had been married, or hooked up, earlier, but there is enough wriggle room in the chronology to cast doubt on Theudebert’s parentage. Tuck that nugget away for later, it will come back.

Childebert was in a good place. He had control over more than half of Francia, potential pretenders had been dealt with. Through a careful policy of carrots and sticks, the nobility seemed to have quieted down. His line seemed secure. He had a pair of healthy heirs to take over when the time came, but he was only twenty-five, so that time still seemed reasonably distant. I am sure, dear listeners, that in my summing up of Childebert’s happy situation, you can hear the creak of Fortuna’s wheel, turning away. And if so, no, you are not imagining it.

“Some thought that they had been poisoned.” Is the sentence in the Chronicle of Fredregar explaining the sudden death in 595 of Childebert II and his queen. That’s it. “King Childebert passed from this world at the age of twenty-five, in the twenty-third year of his reign, … he and his wife died at the same time. Some thought that they had been poisoned.” There’s no hint of who initiated the murder or why, or even where. We can guess, of course, Austrasian nobles feeling suffocated by royal power, maybe, or Fredegund, still there, a dark presence in Neustria, full of malice for the line of Sigibert and Brunhilda. But it would all be guesses and speculation, and I feel like I’ve already done my fair share of speculating in this episode, and we’ve still got ground to cover. So I will simply sum up Childebert II; he had been the king of Austrasia, in name at least, for 23 years, since he was two, and also king of Burgundy for four. He left behind his two sons, Theudebert and Thiuderic, aged about ten and eight, respectively. His wife died at the same time, presumably the victim of the same poison, and so that just left Brunhilda to bury her son, and once again, at the age of 53 or 54, to assume the regency for an underage prince.

Following Frankish tradition, the two kingdoms were separated again, with the elder, Theudebert, receiving Austrasia, while Guntram’s former territories went to Thiuderic. Brunhilda slid smoothly into place as regent of Austrasia, yet another indication of how deeply embedded into the political infrastructure. That she remained with Theudebert isn’t surprising, since Austrasia had been her home for much longer, it was where she had the strongest connections.

The passing of Childebert did not go unnoticed by the neighbors, and Fredegund took the opportunity to organize an attack on the young monarchs. The Neustrians succeeded in capturing Paris outright, which up until now had been held by all the kings in common. It was pretty much the last gasp of Fredegund’s malice. She died the following year, in December 597, “Aged and full of days” in the words of the Chronicler. It’s hard to say with any certainty how old she was, but similar to Brunhila, i.e. mid to late fifties, is probably a reasonable enough guess. She was buried with Chilperic in the church now known as Saint-Germaine-des-Prés in Paris, but both of them were later transferred to the Basilica of Saint-Denis. There is a mosaic cenotaph for her there, dating from the eleventh century.

How Brunhilda reacted to the death of her nemesis, by natural causes, is not recorded. Fredegund’s passing, though, did nothing to ease the hostility between the Eastern and Western halves of the Frankish empire. Both matriarchs had spent decades pouring poison into the ears of their descendants, and so the feud transcended the generations. The king of Neustria, Chlothar II, now around 13 or 14 years old, would spend a few years getting himself settled, but his intentions were pretty clearly bent on expanding his patrimony at the expense of the Thiuderic and Theudebert. They were his nephews, by the way, though he was only three years or so older than Theudebert, I just mention it for interest’s sake, since it can be a little hard to remember that all of these folks are quite closely related. I personally would be irritated if any of my uncles were always trying to steal the tools out of my garden shed, and I imagine when we’re talking about whole cities being at stake, it just raises the temperature at Christmas dinner even further.

Given that the average age of Merovingian kings had fallen down into the teens, Brunhilda was unquestionably the most experienced stateswoman in Francia, which gave her a claim to be the most powerful person in the Latin west, at least for a while. In 596 Pope Gregory sent a letter addressed to both Theudebert and Brunhilda introducing a monk named Augustine and asking that they support him and his companions in their mission. That mission was to the AngloSaxon kingdom of Kent, the first we’ve heard from Britain in quite some time. Augustine would find success across the narrow sea, converting King Æthelbert to Christianity and becoming the first Archbishop of Canterbury. Gregory would write to Brunhilda again later, praising her for her support of the undertaking. There’s more to say about the Frankish church and religion at the time in general, but I’m saving it for our next episode.

Brunhilda’s support seems to have been especially strong among the GalloRoman aristocrats, still distinct enough to be identifiable after all this time. As time went on though, her popularity declined. It’s hard to say why, it may have been dissatisfaction with the queen’s efforts at centralization, it may have simply been that she was seen as arrogant and high-handed, it may have been simple sexism, or a combination of all three. But the years following definitely saw an erosion of support. A case in point was a noble called Wintrion. He was a relative of Lupus, the dux of Champagne, and so had a family tradition of support for Brunhilda’s rule. He had been one of the leaders of the armies of Fredegund. And yet in 597 or thereabouts, he joined a conspiracy against the queen, was caught and executed. Fredregar says he was “entrapped” by the queen, whatever that means. Really it makes little sense for the queen to have actively looked for supporters to screw over, that would seem to be the actions of a complete nut with no foresight whatsoever, or of someone who was dangerously overconfident. Maybe it was the latter, who knows, but eventually, whatever it was came around to bite Brunhilda. It’s worth noting that what’s about to happen would have been around the time that Theudebert was reaching the age of majority, and beginning to take independent action as king, maybe he found his grandmother overbearing and a little suffocating, and so, as soon as it was possible, he gave his nobility the wink and the nod they needed to execute a little coup.

Fredregar says that the Austrasian nobility drove Brunhilda out in 599. The pope was still writing to her as regent of Austrasia as late as 602, though, and he would have been well informed, so the later date is more likely. Indeed, the whole narrative of expulsion found in Fredregar’s chronicle is suspect. “King Theudebert and the barons of his kingdom expelled Brundhild from the land, for the murders and treachery she had performed. A poor man found her alone and distraught; she begged him to lead her to her other grandson, king Theuderic. When she arrived, she was received as his grandmother, for it seemed that he was compelled to treat her with honor. She stayed with him as long as he lived, but it would have been better for him had he banished her, for she later had him poisoned to death, as you will hear afterwards. As a reward for his service, she gave to the poor man who had brought her the bishopric of Auxerre.”

First of all, it is wildly unlikely that a queen, now aged in her late fifties, should be treated in such a way, regardless of what she had been accused of. Second, the bishop of Auxerre at the time was one Desiderius, who is elsewhere noted for having royal blood, which is much more likely. The story seems to be an attempt to slander Brunhilda’s judgement in the distribution of patronage, look how she’ll give high church offices to anyone, even a poor peasant.

It’s high time, actually well past time, for me to talk in more detail about the Chronicle of Fredregar and the problems with it.

I can’t remember how much of this I’ve already mentioned, so bear with me if I repeat myself. The Chronicle of Fredregar did not actually acquire that name until the sixteenth century, until then the document had remained unattributed. It exists today in over thirty manuscripts, the oldest dating to 715, which is pretty impressively old. About three quarters of it consists of other copied works, many of them reworked, including Gregory’s History, along with works of Church fathers like Eusebius and St. Jerome. The part we’re interested in, book IV, was most likely composed in Burgundy, sometime between 660 and 670, as it alludes to (but does not record) events in the 650s. The actual chronicle ends in 642, though some manuscripts include continuations recording the roots of the Carolingian dynasty in the late eighth century.

All of that sounds fine, reasonably contemporary, close to the action. The problem specifically with using Fredredgar as a source for Brunhilda’s activities lies with its own source for the material. The author seems to have drawn heavily on the Life of Saint Columbanus, written by a monk called Jonas of Bobbio. Columbanus will come up next episode, but the problem is that Saint’s lives are extremely tricky to use as historical sources. They were not intended to serve as accurate and complete reckonings of events; rather, they were written to provide edifying examples of piety and uprightness, usually to be transmitted in sermon form to congregations. As a result, they tend to be fairly formulaic, often parallelling biblical stories and themes. Kings and queens are often set up as antagonists to the Life’s holy subject, recapitulating conflicts between Old Testament prophets and kings of ancient Israel. So Brunhilda becomes, for Jonas, a Frankish Jezebel, full of cruelty and opposition to Columbanus, the new Elijah. Fredregar carries that same hostility forward. On the other hand, I have to admit that the Brunhilda that emerges from Fredregar’s narrative, as we have seen a bit already, is a more compelling character than the sanitized version we find, and who always seems just a little out of focus, in Gregory’s. Anyway, just some things to keep in mind.

Regardless of how she made her way to Thiuderic’s Burgundian court, Brunhilda was understandably upset by the way she had been treated. She immediately set about acquiring influence in the new court, presumably working the contacts she’d made in the last years of her son’s reign. She also began to push the idea that Theudebert was not actually Childebert’s son, but the son of a gardener. It’s a pretty wild accusation, but not a new tactic among the Merovingians. Gunthar had raised suspicions about Chothar II’s parentage as well, and unlike Fredegund at the time, Faileuba and Childebert weren’t around to refute the accusation. Animosity between the two brother monarchs grew, and it’s hard to see how it could have been anything other than Brunhilda’s influence at work. Violence broke out, with Thiuderic at first coming out of it better, until external problems forced them the two to patch up a peace and an alliance.

Those external problems had a name: Chlothar II, son of Chilperic and Fredegund. His saber rattling was enough for Thiuderic and Theudebert to call time on their own squabbles – which was quite an achievement given that sabres weren’t really a thing yet. Calling your brother a bastard will start one kind of fight, reminders of intergenerational bloodfeud will start an entirely different kind. Civil war again had to be postponed though. The Saxons made themselves a nuisance in the northeast, as did the Gascons (or Basques) in the southwest, and these had to be dealt with. The war with the Saxon raiders was especially bloody and destructive. Finally though, distractions set firmly to one side, the kings and Austrasia and Burgundy were prepared to beat up on their barely older uncle (now around 16), the king of Neustria.

The two invaded with a large army and met Chlothar’s responding force near a river called the Orvanne. It’s a short little squib of a river mostly in the Ile-de-France, and soon it ran pink with the result of the sharp, hard fought, and bloody battle on its banks. Chlothar was defeated and fled the field. Thiuderic and Theudebert pressed their advantage, and accepted the allegiance of a large number of Chlothar’s former followers. Negotiations followed closely afterwards, and it was a walkover for the brothers. Chlothar’s territories were reduced to just twelve civitates between the River Oise and the Seine. Essentially, a small triangle of territory between Paris and Rheims. The brother’s high fived, split all the loot, and then went right back to hating each other, while Chlothar brooded. None of this did anything to deescalate the spiral of hostility between the two halves of the Merovingian family.

Brunhilda’ attitude toward this success isn’t recorded, though presumably she was pleased. Her activities in Burgundy continued very much in the mold she’d already established. She weathered the potentially dangerous moment when Thiuderic came of age without difficulty, and even found him a wife. Allegedly she bought her from a slave market, once again refusing to introduce a well connected rival into the situation.

She promoted the interests of her favorites and did her best to remove or neuter those who could oppose her. Amongst the former, Fredregar names specifically a man named Prothadius, who, according to the chronicler, was also her lover – we can probably dismiss that idea though, it’s just too on the nose with the Jezebel tropes. She pushed aside a dux named Dalmaris, to replace him with Prothadius, and pressured Thiuderic to give him a prominent role within the king’s close household. The role in question is one that will be coming up a lot in our future discussions of the Franks: the mayor of the palace. The maior – and you can’t hear it but I’m using the latin word M-A-I-O-R, which means greatest or most important, was the chief manager of all of the king’s household. He (and it was always he, as far as we know) oversaw everything necessary to make sure his lord had everything he needed, ideally before the lord knew he needed it. The position existed in most great households, and in the case of the king’s household, it carried enormous influence, especially as the king became more and more dependent on their maior, but that’s a story for much later.

Anyway, the maior at the time was a baron named Berthoald, and he and the king were close, rather than attacking directly, Brunhilda suggested that Thiuderic send him to inspect royal villas. Berthoald set out on his mission, but in the process met the maior of Chlothar, a man named Landry. Brunhilda had contacts in the Neustrian court as well, and had arranged this little ambush. Berthoald fought bravely, but was surrounded and killed, and Bob’s your uncle, Prothadius was right in there as his replacement.

Prothadius was greedy but perfectly competent, and that combination worked out well, since increasing royal revenue increased his opportunities to skim off the top. Everybody wins, especially Brunhilda, who had a direct channel of communication to the king in his most intimate circles. Prothadius didn’t last long, though, killed by the other barons while on an abortive campaign against Theudebert. It was the same perpetual push and pull, the magnates in their factions versus the king or queen and theirs. It’s all extremely personal and cutthroat. You’ve probably noticed that there hasn’t been a lot of policy discussion in this episode, these factions were not necessarily aligned behind one fiscal policy or another, but were mainly the games of personal power. The line between political violence that we might call war, and personal violence that we might call crime, is pretty much nonexistent.

In Fredregar’s Chronicle, the list of barons and household men evicted from court by Brunhilda’s schemes is significant: Berthoald, Uncelinus, and Volfus can be added alongside Ursus and Berthefried. Most of those will just be names to you, but they serve the point that I keep hammering, that Brunhilda bent all her political efforts toward maintaining and extending her influence over the Frankish kingdom. The church was no different. Bishops who threatened Brunhilda’s position were maneuvered out of their positions, and in the case of Desiderius of Vienne, who preached a sermon against her, assassinated. Whenever possible, she pushed her own candidates into vacant dioceses. One of those might have been Gregory of Tours himself, as I mentioned earlier.

All of this carried on in the background to the never ending Merovingian territorial rivalries. Even without the personal animosities and lingering vendettas, Thiuderic and Theudebert squabbled over land constantly. War between the two broke out in 604, 605, and 608. In 612, Thiuderic had had enough. He secured a promise of neutrality from Chothar, and then set out to take back the lands he had lost with a huge army. Theudebert mustered his own men, and the two armies met in battle, first at Toul, then at Zulpich. Both times, Theudebert’s force was beaten, at Zulpich “the fighting was so bitter and intense on both sides, and they attacked each other with such hardiness, that the dead remained on their horses as though they were still alive, nor were they able to fall, because they were packed in so closely with the living; they were pushed here and there by the movement of those battling.” Beaten, Theudbert fled eastward to Cologne, but was betrayed by the locals, taken prisoner, and beheaded.

We’re nearing the end of Brunhilda’s story, and, to be honest, it’s not pretty reading. There is another version where Theudebert was given to Brunhilda as a prisoner, and that it was she that had him murdered after a brief captivity. It was also she, according to Fredregar, that killed Theudebert’s young son, Merovech, with a rock, with her own hands. Theudebert II was about 27 when he died, and had been king of Austrasia for 17 years. Thiuderic took over all of his brother’s lands, there being no male heir, now.

Burgundy and Austrasia were once again united, as they had been under Childebert. Minus a chunk that Thiuderic ceded to Chlothar in gratitude for his neutrality.

Not all of Theudebert’s children had been killed, namely his daughters. One of them apparently captured Thiuderic’s attention, in an aesthetic appreciation and desire kind of way. I’m not at all comfortable with how the math works out on ages here, so I’ll gloss over that issue without thinking too hard about it. Brunhilda pointed out to Theuderic that this girl that he was lusting after, and talking about marrying, was, you know, his niece. Even for the Merovingians, that was a little bit beyond the pale. And that’s where it all came down. It’s a little like that scene in Inglorious Basterds where Michael Fassbender uses the wrong fingers to order three glasses in the German bar, and gives himself away. Thiuderic thought about what his grandmother had said, and the penny dropped.

In Fredregar’s telling he said: “‘Oh, you faithless woman, despised by God and by all the world, against everything good, didn’t you insist that he was not my brother, but the son of a shoemaker? Why did you compel me to commit a sin by killing him, and, manipulated by you, to become my brother’s murderer?’ Saying this, he drew his sword and rushed at her to kill her, but the bystanders intervened and led her out of the hall; thus she escaped, this time, imminent death. From that point on she plotted to avenge this humiliation, and to bring about his death; she saw a chance to do this when he was taking a bath. To the ministers who surrounded him, whom she corrupted with promises and gifts, she gave poisons, and ordered them to give them to the king to drink when he was to come out of the bath. The king drank the poison that they offered him, and died instantly, without confessing, without repenting for the great sins that he had committed throughout his whole life.”

Theuderic had had four sons by various mistresses, and Brunhilda’s plan was that Austrasia would pass to one of these, Sigibert. The rest of the kingdoms would pass to Chlothar. Chlothar was having none of it though. Sigibert was illegitimate, as far as he was concerned, and he would have the whole kingdom, thank you very much. Brunhilda was prepared to put up a fight, and made preparations. Much of the Austrasian nobility, though, had had it up to here. Sigibert was indeed illegitimate, and even if not, he would certainly be under the thumb of Brunhilda, and it would just be more of the same. Enough was enough. Plans were laid and plots were hatched.

When the two armies met, anti-climax was the word of the day. A handful of Austrasians had already joined Chlothar, and those that remained on Sigibert’s side abandoned the field without a fight. Sigibert and two of his brothers, Corbe and Meroveus, were captured, the fourth, who happened to have the best horse, escaped and was never heard from again. Chlothar proceeded to have two of the remaining executed, but Meroveus he spared and sent to be brought up and educated in his own household. That was because, fascinatingly, Chlothar was the boy’s godfather.

The jig was finally up. Had the battle gone differently – had there been a battle at all, really – then the defeat and probably killing of Chlothar would have been the icing on the cake of Brunhilda’s bloodfeud. Fredegund’s son made to pay for the wrongs she had visited upon Brunhilda and her family. As it was, Chlothar was equally prepared to bring matters to a conclusion. He brought Brunhilda before the assembled nobility of Francia and accused her of causing the deaths of ten kings, including her husband Sigibert, her son, and her grandsons. He undoubtedly laid murders at her door that were really his mother’s work, but now was not the time to be fair and balanced. All of it would end today. This was not a trial, Brunhilda was clearly guilty, all there was to be done was determine how she would die.

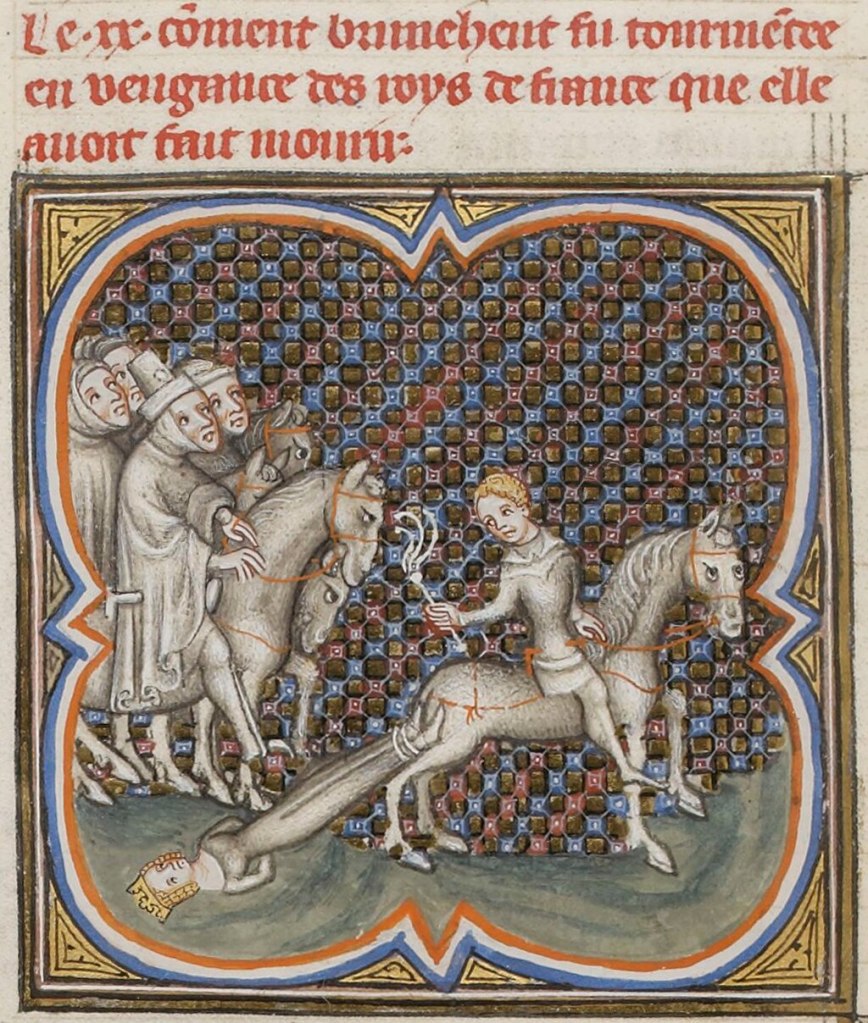

The method chosen would fit perfectly into the traditions of German heroic poetry and Norse saga, i.e. it was public and brutal. The aged queen, nearly 70 now, was tied to a horse, and dragged through the army camp until she was dead, and then for a while longer. It was an undignified end for anyone, and especially for a woman who had been at the center of Frankish politics for half a century.

So what do we think?

At the end there, Brunhilda seems to have gone pretty thoroughly off the rails, if we take Fredregar at face value. Even if we allow for some exaggeration, I think we can say that she was a pretty ruthless operator, concerned mainly with her own position, secondarily with the standing of her family. The running feud with Fredegund and her son probably did contribute a toxic element that intensified conflicts. There was no clear line between state policy and personal power and position.

It’s got to be said that in this, she probably was absolutely no different from any other powerful person in the Frankish courts, or in any courts for that matter. Assassination and violence were in the air, and the nobles competed and fought each other with just as much cynicism as the Merovingian royals did. Even by the worst interpretation, up until the end, Brunhilda mainly gives the impression of amorality and probably a talent for rationalization; there’s very little sign of sadism. By way of contrast, Gregory tells of one Frankish magnate who, at dinner, would make a servant hold a lit candle between his thighs until it burned him, and of another who buried a peasant couple alive because they had married without his permission. I’m not making excuses for Brunhilda, if she really did murder her own great grandson with a rock, surely a line has been crossed. I’m just making the point that it was a violent society, and one with very few limits at all on the behavior of the elite.

Brunhilda stands out for two reasons, first, because she was a queen and therefore had access to much wider resources with which to manipulate the body politic, and two, because she was a woman, and there has hardly ever been a time when chroniclers and commentators have not applied the old double standard. Namely, that the ambition, aggression, and cunning that may be admirable in a man, is detestable in a woman. The presentation of Brunhilda and Fredegund, and in a different light, Radegund, makes it clear that queens were significant and powerful figures in Frankish politics, and were feared and respected.