The year was 577. The place, the church of Saint Peter the Apostle, in Paris. The interior was dim, the bright sun outside reduced to dust-spangled shafts from the windows along the south wall. It was noisy, a hubbub of chattering voices, both inside and out. A crowd milled about outside, unseen, but their presence felt by everyone in the room. A threatening edge hovered in the noise. The room was large and rectangular, with pillars forming three aisles from the door down to the end. Down there, in the recessed apse, a wooden dais had been built, with a single chair upon it, decorated with draperies of finely made wool and silk. On either side of the center aisle, there were two sets of temporary risers, and on those risers sat the source of some of the din. Forty five men, dressed in similar robes of simple design but obvious quality, talking amongst themselves. These men were bishops of Neustria, called to this meeting by their king. Other men filled out the risers, deacons and secretaries of the prelates, some chatting along, some listening to other conversations intently, making mental notes. One bishop sat apart from the others, fidgeting with the hem of his robes, looking troubled.

The doors pushed open with a rattle, and the murmuring of the crowd spilled inside around the shoulders of the King as he strode into the church. Half a dozen companions followed. All were richly dressed, in materials as fine as the bishops, and much more colorful. King Chilperic, for ‘twas he, clad in a mantle of wool trimmed with silk, with embroidered medallions and draped over one half of his body, in the style of Constantinople. His hair flowed in waves down the back of his neck, under a simple gold circlet. The hair was as much a sign of his regality as any crown would have been. Everyone stood as he made his way down the aisle and climbed the dais. His companions arranged themselves on either side of him. They were unarmed, except their belt knives, in deference to the sacred space, but each of them bore the scars and hard looks of a lifetime of violence. The king’s eyes scanned the waiting clerics with a similar hardness.

A hush descended as the doors closed and Chilperic settled back in his chair. There was no formal announcement of the purpose of this council, that had already been done yesterday. This day’s business was well known to everyone and dreaded by some. After one of the deacons offered a prayer asking God’s blessing on this afternoon’s discussion, one of the king’s companions stepped forward.

“Praetextatus of Rouen, step forward!”

The worried looking bishop rose, composed his face, and stepped into the aisle to face the king. A long moment of silence.

The king leaned forward, his elbow on one knee. When he spoke, his tone was measured and dangerous, everyone in the room could hear him, though he did not shout.

“What was in your mind, bishop, when you performed the wedding of my enemy, Merovech, who should be my son? You must have known that marrying his uncle’s widow, his own aunt, is forbidden by the canons of the Church. Further, what is in your mind when you accepted Merovech’s treasure, and set about using it in nefarious and unholy ways. I accuse you, bishop Praetextatus of Rouen, of acting against the law of God’s holy church, and of conspiring to turn the loyalty of the people against their rightful king, and further, of conspiring with certain others to bring about my own death, and deliver my kingdom into the hands of another. “ His voice rose toward the end, so that he nearly was shouting. At his last word, an angry roar rose from outside; the crowd had been listening, and they were the king’s men. The doors rattled again as the crowd pounded on them, and Praetextatus flinched. The king mumbled something to one of the men at his side, who slipped out, and the noise subsided.

A raised royal eyebrow prompted the bishop to fall to his knees and desperately deny the accusations. “I know nothing of these conspiracies, my lord king! Never did I seek to dissuade your subjects from their loyalty, and never have I even thought of your death, may God forbid it!”

Chilperic let him go on for a while, until he ran out of steam and began to stutter, then raised a hand for silence. “Bring in the witnesses, ” he said simply.

A handful of men were led in, of various ranks, to judge by their clothes. Praetextatus’ shoulders sagged as he watched them, a look of hurt resignation on his face. One by one the men produced valuable objects; a belt decorated with gilded studs, a cloak pin with garnets, a pendant made of an old gold coin, surrounded by pearls. Each one swore that the thing was given to them by the bishop, in an effort to tempt them into renouncing their loyalty to the king. One by one, Praetextatus gave the same answer, “It was merely a gift? You have given me fine gifts, horses, and other things, what could I do but make similar presents in my turn?” But it was hopeless, and he knew it.

Satisfied that he had made his point, the king rose and strode out of the church, followed by his men. Praetextatus slumped miserably out as well, to go and wait for the council’s decision at the episcopal palace, where several of the men who were to decide his fate were also staying.

There were a few voices raised on the accused’s behalf; Aetius, the archdeacon of St Peters and Gregory the archbishop of Tours both spoke with great conviction. Their words were reported back to Chilperic, who summoned the bishop to see him. He promised that whatever happened, he, the king, would abide by canon law, and Praetextatus would be treated fairly. Buoyed by these and other assurances, the bishops convinced Praetextatus to change his plea, and admit to the minor charges, in expectation of a royal pardon.

But the king had no intention of letting it go. After Praetextatus had finished his submission and confession, a group of bishops aligned with Chilperic produced an obscure and seldom-used canon of the law that stipulated that a bishop guilty of perjury should be deposed. Praetextatus had admitted that he had lied in his original pleading, ergo, he was declared guilty, and the council, caught on the horns of the king’s maneuver, was forced to concede.

Praetextatus was excommunicated, stripped of his position, and sent into exile on an island, probably Jersey.

The persecution of Praetextatus – later to be venerated as Saint-Prix – is one of the central pillars of Gregory of Tour’ conception of him as a tyrant, and is one of the detailed and colored personal anecdotes that make Gregory so readable. It also, and here we come to the point of today’s episode, illustrates an important point. The bishops of Francia were representatives of the universal church of Jesus Christ, but that did not mean that they were immune from the authority of their secular rulers. You may have noticed that nowhere in this story was there any suggestion that Praetextatus might appeal the king’s ruling. Not to an archbishop, and the pope isn’t even thought of. There is a temptation to project the image we have of the later Catholic church (if you have such an image) backward into Post-Roman times. That image, for me at least, is of the church as a corporate entity, fully conscious of its existence as a complete, independent, and sovereign institution. Of an institution that arched over the whole Latin west, dictating belief and maintaining conformity, sometimes with vicious repression. All of it firmly under the rule and control of the Bishop of Rome. The pope.

Today I’m going to talk about how that really was not true in the kingdoms of the sixth century and later. The process of fragmentation that followed the fall of the west affected the Church just as much as it did other parts of society, and there was a process of remaking that was very national in nature (though that word is a little bit anachronistic). All the bishops and priests recognized that they were brothers in the same family, they would have been horrified at the idea of there being separate churches; but they would have equally been nonplussed at the idea that they were all subject to the central authority of the pope. I’ll talk about the ideology that had prevailed before 476 and how it shifted in the aftermath and the status of the pope in the west. I’ll also talk about the structure of the church that did exist, mainly in Francia, but we’ll range around a bit along the way. We’ll talk about how the largely urban phenomenon of Christianity was carried out into the countryside, and I’ll take a stab at describing what going to church was like for the average Thomas, Ricardus, or Henricus, as far as we can know.

Now, that is a pretty wide-ranging brief, and as I was writing this episode, I looked up at the halfway point and discovered that the thing was threatening to turn into another record breaker. So I decided to take the coward’s way out and split it into two parts. This episode, we’ll do the high level stuff, the bishops and the pope, and then we’ll get local in part two. Probably talk a little bit about monasticism next time too. Good plan?

I take your silence as consent, as always.

One quick declaration before diving back in: I usually do my best to use a reasonable balance of sources when putting together an episode, but in this case I have relied heavily on Christendom: The Triumph of a Religion, by Peter Heather. It came out in 2022 and so is a solid summary of the most recent research into the early church, both intellectually and physically. Seriously, it’s a doorstop, but also engaging, clear, and thorough, as Peter Heather usually is. A lot of newer research has challenged the traditional narrative that the Catholic church represented a continuity with the Roman empire. Instead the modern scholars Heather summarizes along with his own view have come to see the period after 476 as a time of profound change in the church, as it was everywhere else. So, let that serve as both a disclaimer and a book recommendation.

To know where you’re going, you first have to know where you’ve been. Is that actually true? I hope so, otherwise there’s no point in spending your time doing history podcasts. Anyway, to start a discussion about how the church changed after the fall of empire, we need to establish what the church was like before the fall of empire.

Ever since Constantine had made Christianity the official religion of the Roman empire, emperors had seen it as their job to ensure that the church was as well run as any part of the state apparatus. The ideological base on which the whole concept of imperial power had always been that emperors were chosen directly by the divine, and that their status was confirmed by military success. That ideology barely budged with the transition from pagan to Christian. Following that logic then, the emperor was obviously the head of the church as he was the head of every other hierarchy, who could argue otherwise?

Constantine certainly took this view, and shaped the form that imperial leadership would take. He was a man with an eye for detail and saw himself in very exalted terms. All the factions and arguing between the bishops about the nature of Christ and the relative positions of the trinity had been tolerable before the emperor’s name was attached to it. Now, though, all the arguments reflected poorly on the emperor. He was the chosen representative of God, he should have control over his church just as he had control over his army. Unity had to be imposed, divisions had to be resolved, and Constantine called the first Council of Nicaea to resolve them.

I’m not going to hash out the conclusions of Nicaea again or any of the councils that followed it, the point for today is they were called by the emperor. Their agendas were largely set by the emperor, and their final conclusions had to be approved by the emperor. Probably equally important, they were mainly funded by the emperor. Nobody else could have afforded to subsidise the lodging of several hundred bishops and their staff, not to mention the cost of travel.

So what happened when the emperor suddenly wasn’t around anymore?

Actually western bishops had largely been absent from the great councils of the past. They sent observers, at times the bishop of Rome would send his views on the issues of the moment in written form, to be read into the record. Conciliar decisions took time to percolate to the outer edges of the empire, but their authority was recognized, as was that of the emperor.

When the empire was no longer present, however, the ties were weakened. Communication was harder, the bishops no longer had the emperor to act as final arbiter in any disputes. They could and did write to him, but the kings who were now in charge would really prefer they not involve him in the daily affairs of the new kingdoms, thank you very much. But decisions had to be made and disputes still had to be settled, so Church councils began to be organized on a kingdom-by-kingdom basis. Travel was still expensive of course, the basic verities hadn’t changed, so it was the kings who funded these councils. The bishops were integral to the running of the kingdom, so he stumped up. And by doing so, the kings took on some of that imperial authority. Now it was they who called councils, sometimes attending them, sometimes not. They set agendas and determined outcomes, often before the council even convened. These mainly dealt with more local matters, such as the behavior of bishops themselves, or details of practice, but they did make changes to canon law within the kingdom, and so the practice of the regional churches gradually drifted apart from each other.

We start to see more and more local gatherings of this kind as time passes, with meetings of the Frankish church occurring regularly throughout the sixth century. Clovis called the council of Orleans in 511, there was the Synod of Paris in 573, called by Guntram and another in 577 called by Childperic, also in Paris. That second one is the one which gave Bishop Praetextatus so much trouble. This wasn’t solely a Frankish phenomenon, the bishops of the Visigothic Kingdom met regularly, almost always in Toledo, their most famous meeting being the one called by King Reccared in 589 where he officially converted the kingdom to Catholic Christianity and consigned Arianism to the dustbin of history.

All these councils were aware of each other, bishops communicated with each other regularly, and generally tried to keep themselves facing in the same direction, especially when it came to doctrine. Even so, by increments, the church establishments were drifting gradually apart. At the same time, the role of bishops was becoming more defined. This period of church history, by the way, sometimes goes by a name: the Conciliar Era.

There has been a tradition that characterized the Church as simply a continuation of the Roman empire’s administration in a different form. I may have been guilty of promulgating that tradition myself, though I’m not going back through my scripts to know for sure.By implication then, the pope is sometimes seen as sliding smoothly into the hole left behind by the emperor.

As we’ve already seen, that was absolutely not the case. Just a couple episodes ago we talked about how large the imperial government had become, and how very puny was the church in comparison. The bishops never could have assumed all the responsibilities of the empire, even if they had wanted to. In the early days following his official conversion, Constantine had actually envisioned a significant and much expanded role for bishops in the provincial bureaucracy, with administrative and judicial responsibilities. It didn’t work, the bishops didn’t have the time or the training to handle the work. Later on, after more of the classically trained Roman aristocracy had moved into the diocese, it may have worked, but by then the moment had passed. When the empire disappeared, bishops did often take over municipal responsibilities, especially what we might call the social safety net. A bishop, though, had nowhere near the coercive power of enforcement that any government needs to function. That power belonged, wholly and completely, to the new kings

In principle, new bishops were elected by local clergy and consecrated by other bishops, the consecration intended to maintain an unbroken line of succession back to the Apostles. In practice, though, the choosing part often fell to the kings. Candidates would be proposed by the clergy, but it was absolutely clear and understood that a candidate without royal support would find it very difficult to assume their position. It was absolutely commonplace for the candidates proposed by the local community to have been “suggested” by the king. Any convocation that installed a bishop against a king’s wishes would find themselves at the sharp end of the royal displeasure.

In addition to the obvious advantage to kings to have loyal bishops in his kingdom, the positions were an irresistible form of patronage. The diocese, just like the estates of magnates, came along with a package of land, the produce of which supported Church operations, and kept the bishop in appropriate magnificence. You may remember I mentioned Bishop Felix of Nantes, whose favorite estate included 3,000 hectares of vineyard and farms along the banks of the Loire. The income from that spread, along with the other estates in the cathedral’s portfolio, would be split four ways, with equal shares going to maintaining the fabric of the building and its vestments, the clergy, the poor, and the remaining quarter to the bishop himself. That was the tradition in Francia, in the Visigothic kingdoms, income was split three ways, with the poor dependent on the generosity of clergy and bishop. The point of all of that is one that I’ve made before: a bishopric was a major financial windfall. Some were richer than others, but all were attractive and competition for them was intense.

It shouldn’t be too surprising then, that kings would often grant bishoprics as rewards to their favored nobles. It was an especially handy reward for kings to have available, since it didn’t require the king to give away any of his own land.

The practice opened bishops up to criticism in two ways. The first is probably pretty obvious; plenty of the nobles made bishops saw no reason for their lifestyles to change. They carried on feasting, drinking, hunting, and sometimes even riding to war. The more fastidious bishops and metropolitans deeply disapproved, and councils attempted to curb this kind of behavior, with limited success. The second problem was less obvious, but possibly more insidious. The culture of the Franks, and of pretty much everyone else, really, was a gifting culture. It was alluded to in the story of Praetextatus. Your king has given you this wonderful collection of lands and honors, it’s expected that you will give him a gift in return. Mutual gift giving was one of the sinews of social relations, and of a fair proportion of the economy. But where is the line between offering a gift in gratitude, and buying a bishopric? Simony, the purchase of church positions, was anathema to church leaders. It’s named, by the way, after Simon Magus, who in the Acts of the Apostles offered Peter and John cash in exchange for their powers of healing. Peter cursed him, “For I see that you are in the gall of bitterness, and in the chains of wickedness.” (Acts 8:14-24)

The simony problem would dog the church for centuries. It would, in a few hundred years, become one of the hinges on which church reforms would swing, reforms that would end with the supremacy of the pope and the creation of the medieval church that lives in the popular imagination. In our period though, the pontiff was, comparatively, nowhere, in spite of the popes’ own pronouncements.

The bishop of Rome was the most prestigious of all the western prelates, that much was agreed by everyone. That prestige was founded on a few foundation stones. First, there was the connection to the city of Rome itself; the city’s Christian community was the largest in the west from the beginning. Emotionally, Roma aeterna still had a special place in the hearts of the upper classes. That was enhanced by its status as the site of martyrdom of Peter and Paul, two apostles. That was, as the popes would occasionally point out, one hundred percent more apostles than any of the other patriarchs could claim. Guardianship of the two saints’ relics brought further kudos. But the biggest, most massive foundation stone for papal authority was, and still is, the principle of Petrine primacy. In this formulation, Peter was the foremost of Christ’s disciples, as confirmed out of Jesus’ mouth the Gospel of Matthew: “And I tell you, you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church, and the gates of Hades will not prevail against it. I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven, and whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven.” (16:18-19) Peter was the foremost disciple, the popes reasoned, therefore his apostolic successor, in an unbroken chain of consecration from the apostle himself, must also be the foremost bishop, and inheritor of all of Peter’s authority and powers.

The thing is though, prestige is not the same thing as power. The bishop of Rome’s assertions were all very well, but they had little practical effect. For one thing, other bishops pointed out, there was no scriptural evidence that they could find to support the idea that the powers Christ had conferred on Peter actually were passed along with the succession. And if they were, they were not possessed by all the bishops collectively. The general opinion was that among the five patriarchs of the Christian Church (Rome, Constantinople, Antioch, Alexandria, and Jerusalem), Rome was to be respected, even acknowledged as first amongst equals, but deferred to without question? Nah.

That attitude pretty much prevailed amongst the lesser bishops of the west as well.

Popes kicked against this attitude periodically. Beginning with Innocent I (401-417) the popes’ response began to come in the form of the decretal. A decretal is a formula for responding to a query from a correspondent. The response was written on the same scroll, below the original request. The thing about decretals was that they were the standard form for communications from the emperor to governors and other bureaucrats. The implication from Innocent and those that followed him was that these decisions were legally binding. Leo I (440-461) built on the idea by claiming the right to act as a court of appeal for western bishops, and to bestow the badges of office (the pallium) on archbishops. In 445, Valentinian III was even prevailed upon to give legal force to these papal assertions, declaring that “if the authority of the Apostolic See has sanctioned or should sanction anything , such regulation shall be as law.”

After the disappearance of imperial authority from Italy, the effort was stepped up. Pope Gelasius (492-496) was especially bolshy. In 496 he wrote to emperor Anastasius: “There are two powers which for the most part control this world, the sacred authority of priests and the might of kings. Of these two the office of the priests is the greater in as much as they must give account even for kings to the Lord at the divine judgement… You must know therefore that you are dependent upon their decisions and they will not submit to your will.” That was a wild claim, and completely contrary to the ideology that had governed the church up to that point. Essentially Gelasius was creating what we would call the secular sphere, entirely separate from the sacred, and pushing the emperor into it.

In the sixth century, a scholar by the name of Dionysius Exiguus labored to bring together a collection of canon law, compiled with great effort the rulings of ecumenical and regional councils, along with all the papal decretals that could be found. In his commentary Dionysius Exiguus made the assertion that papal decretals were as authoritative as the rulings of ecumenical councils. He also was the first to propose the anno domini system of dating, though it would be a while before it became popular. Fun fact.

So all of those 350-odd words seem like the opposite of what I’m claiming. It all sounds like exactly the kind of supreme authority that the popes of the high middle ages claimed. And let me tell you, those later popes absolutely used all of these points to make their case for that authority. But there are problems with that conclusion.

Starting with decretals. Dionysius Exiguus was a careful researcher, and for the first 120 years covered by his compilation, he found only 41 decretals had been issued. That’s an average of about one for every three years. For comparison, in the 12th century, the papal see was issuing 30 per year, ten times as many. Decretals were written in response to queries from other bishops, and other bishops just weren’t asking much. Nor did the popes have any kind of apparatus to go out and find issues to resolve, there was no system of papal representation outside his own metropolitan territory of the South of Italy and Sicily.

Gelasius’ letter had come at a very specific time, after the Ostrogoths had established themselves in Italy, and during the Acacian Schism. That’s an episode that I’ve often thought about re-writing, but now is very much not the time. The point is that Gelasius was in a safe position from which to needle the emperor without fear of immediate retaliation. Once Belisarius had recaptured Rome, Gelasius’ letter sank without a trace, and popes once again came under the sway of the emperor. At one point, three Greek-speaking popes in a row were installed by Constantinople, so complete was the imperial hold over the office. Gelasius’ letter would be dug out again in the 12th century, and quoted in every work of canon law from then on, but in the decades after 530, it was pretty much entirely forgotten.

And just to tie up loose ends, that declaration by Valentinian III? Valentinian was a remarkably weak ruler, and that would not be the only of his declarations that ultimately left no mark on the course of immediate events. We can put that edict aside as irrelevant. Harsh, but true. Popes really really really wanted to be the arbiters of western Christendom, but in the sixth, and seventh, and most of the eighth centuries, the rest of western Christendom was content to listen politely, thank him for the input, and get on doing whatever they were going to do anyway.

The attitude of the provinces is summed up by a letter written in 648 by bishop Braulio of Zaragoza to pope Honorius. The pope had taken issue with what he saw as the Visigothic bishops’ failure to enforce discipline amongst the clergy and correct episcopal abuses. Braulio wrote on behalf of all the bishops gathered for the sixth council of Toledo, and they were disinclined to accept the Pope’s criticism: “We did censor transgressors, and we did not keep silent when it was our duty to preach. Lest your apostolic highness think that we are producing this to excuse ourselves and not for the sake of truth, we have deemed it necessary to send you the previous decrees along with the present canons.” The whole thing is very recognizably in the tone of “per my last email”, and Braulio closed by pointing out that the verses that Honorius had used to support his arguments were from Isaiah, not Ezekiel as the Pope had said. All in the most diplomatic, careful language, but the overall message: you do your job and let us do ours, is as plain as day.

I have talked for too long, and if I keep going this is going to become another record breaker. So I’ll leave the religion of the common folk until next time, along with some talk of monasteries and such. Honestly, there’s so much to talk about it could swallow the whole podcast, but I’m pretty sure you’d all abandon me. So to close today, let me just finish us off with the story of bishop Praetextatus.

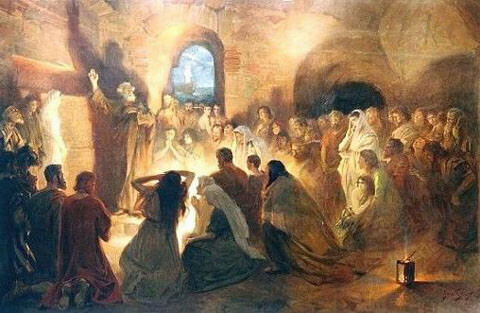

The unfortunate bishop spent several years on Jersey, until 584, when Chilperic died. He lobbied king Guntram to review his case, and to be restored to his old job as bishop of Rouen. Guntram agreed and heard evidence from interested parties. One of those parties was queen Fredegund, who Gregory partially blamed for bringing the prosecution in the first place, but she was overridden, and Praetextatus returned to Rouen. He had spent his time in exile writing prayers and poetry, as you do, and shared them with his colleagues at a council in Macon, to mixed reviews. In 586, Praetextatus had a sharp argument with queen Fredegund, a “bitter exchange of words”, as Gregory put it. “She told him that the time would come when he would have to return to the exile from which he had been recalled. ‘In exile and out of exile, I have always been a Bishop,’ replied Praetextatus, ‘but you will not always enjoy royal power…when you give up your role as Queen you will be plunged into the abyss…’ The queen bore his words ill.” A while later, during Easter services, Praetextatus was stabbed and wounded by an assassin. He was carried to his bed, but it was clear the wound was mortal. Fredegund came to visit the dying man and expressed horror that such a thing should have happened. Praetextatus was having none of it, and accused her directly of both his own murder and many others. He refused the doctors that the queen offered him, and before dying, cursed Fredegund and promised divine retribution. This confrontation has appeared in art, one painting by Lawrence Alma-Tadema,reminds me of the death of Socrates, though its emotional tenor is very different. I’ll put it on instagram.

I have talked long enough. Come back next time, so I can yap at you some more. We’ll talk about the problem the church faced in carrying its message to the rural peasants who made up more than 90% of the population, and about the actual experience of attending church in the time of Gregory of Tours. Until then, thank you for listening, and look for the show on instagram @darkagespod. Take care.

The doors are pushed open with a rattle, and the murmuring of the crowd spills inside around the shoulders of the King as he strides into the church. Half a dozen companions follow behind. All are richly dressed, in materials as fine as the bishops, and much more colorful. King Chilperic, for it is he, wears a mantle of wool trimmed with silk, with embroidered medallions and draped over one half of his body, in the style of Constantinople. His hair flows down the back of his neck, under a simple gold circlet. The hair is as much a sign of his regality as any crown would be. Everyone stands as he makes his way down the aisle and climbs the dais. His companions arrange themselves on either side of him. They are unarmed, except their belt knives, in deference to the sacred space, but each of them bears the scars and hard looks of a lifetime of violence. The king has a similar look in his eyes.

A hush descends as the doors are closed and Chilperic settles back in his chair. There is no formal announcement of the purpose of this council, that has already been done yesterday. Everyone knows today’s business, and many dread it. After one of the deacons offers a prayer asking God’s blessing on this afternoon’s discussion, one of the king’s companions steps forward.

“Praetextatus of Rouen, step forward!”

The worried looking bishop rises, composes his face, and steps into the aisle to face the king. A long moment of silence.

The king leans forward, one hand on his knee. When he speaks, his tone is measured, and dangerous, everyone in the room can hear him, though he does not shout.

“What was in your mind, bishop, when you performed the wedding of my enemy, Merovech, who should be my son? You must have known that marrying his uncle’s widow, his own aunt, is forbidden by the canons of the Church. Further, what is in your mind when you accepted Merovech’s treasure, and set about using it in nefarious and unholy ways. I accuse you, bishop Praetextatus of Rouen, of acting against the law of God’s holy church, and of conspiring to turn the loyalty of the people against their rightful king, and further, of conspiring with certain others to bring about my own death, and deliver my kingdom into the hands of another. “ His voice rises toward the end, so that now he nearly is shouting. As he finishes the last word, there is an angry roar from outside; the crowd has been listening, and they are the king’s men. There pounding on the doors, and Praetextatus flinches. The king speaks to one of the men at his side, who ducks outside, and the noise subsides.

A raised royal eyebrow prompts the bishop to fall to his knees and desperately denies the accusations. “I know nothing of these conspiracies, my lord king! Never did I seek to dissuade your subjects from their loyalty, and never have I even thought of your death, may God forbid it!”

Chilperic lets him go on for a while, until the bishop has run out of steam and begins to stutter, then silences him with a raised hand. “Bring in the witnesses, ” he says simply.

A handful of men is led in, of various ranks, to judge by their clothes. Praetextatus’ shoulders sag as they come in, a look of hurt resignation on his face. One by one the men produce valuable objects; a belt decorated with gilded studs, a cloak pin with garnets, a pendant made of an old gold coin, surrounded by pearls. Each one swears that the thing was given to them by the bishop, in an effort to tempt them into renouncing their loyalty to the king. One by one, Praetextatus has the same answer, “It was merely a gift? You have given me fine gifts, horses, and other things, what could I do but make similar presents in my turn?” But it was hopeless, and he knew it.

Satisfied that he had made his point, the king rose and strode out of the church, followed by his men. Praetextatus slumped miserably out as well, to go and wait for the council’s decision at the episcopal palace, where several of the men who were to decide his fate were also staying.

There were a few voices raised on the accused’s behalf; Aetius, the archdeacon of St Peters and Gregory the archbishop of Tours both spoke with great conviction. Their words were reported back to Chilperic, who summoned the bishop to see him. He promised that whatever happened, he, the king, would abide by canon law, and Praetextatus would be treated fairly. Buoyed by these and other assurances, the bishops convinced Praetextatus to change his plea, and admit to the minor charges, in expectation of a royal pardon.

But the king had no intention of letting it go. After Praetextatus had finished his submission and confession, a group of bishops aligned with Chilperic produced an obscure and seldom-used canon of the law that stipulated that a bishop guilty of perjury should be deposed. Praetextatus had admitted that he had lied in his original pleading, ergo, he was declared guilty, and the council, caught on the horns of the king’s maneuver, was forced to concede.

Praetextatus was excommunicated, stripped of his position, and sent into exile on an island, probably Jersey.

The persecution of Praetextatus – later to be venerated as Saint-Prix – is one of the central pillars of Gregory of Tour’ conception of him as a tyrant, and is one of the detailed and colored personal anecdotes that make Gregory so readable. It also, and here we come to the point of today’s episode, illustrates an important point. The bishops of Francia were representatives of the universal church of Jesus Christ, but that did not mean that they were immune from the authority of their secular rulers. You may have noticed that nowhere in this story was there any suggestion that Praetextatus might appeal the king’s ruling. Not to an archbishop, and the pope isn’t even thought of. There is a temptation to project the image we have of the later Catholic church (if you have such an image) backward into Post-Roman times. That image, for me at least, is of the church as a corporate entity, fully conscious of its existence as a complete, independent, and sovereign institution. Of an institution that arched over the whole Latin west, dictating belief and maintaining conformity, sometimes with vicious repression. All of it firmly under the rule and control of the Bishop of Rome. The pope.

Today I’m going to talk about how that really was not true in the kingdoms of the sixth century and later. The process of fragmentation that followed the fall of the west affected the Church just as much as it did other parts of society, and there was a process of remaking that was very national in nature (though that word is a little bit anachronistic). All the bishops and priests recognized that they were brothers in the same family, they would have been horrified at the idea of there being separate churches; but they would have equally been nonplussed at the idea that they were all subject to the central authority of the pope. I’ll talk about the ideology that had prevailed before 476 and how it shifted in the aftermath and the status of the pope in the west. I’ll also talk about the structure of the church that did exist, mainly in Francia, but we’ll range around a bit along the way. We’ll talk about how the largely urban phenomenon of Christianity was carried out into the countryside, and I’ll take a stab at describing what going to church was like for the average Thomas, Ricardus, or Henricus, as far as we can know.

Now, that is a pretty wide-ranging brief, and as I was writing this episode, I looked up at the halfway point and discovered that the thing was threatening to turn into another record breaker. So I decided to take the coward’s way out and split it into two parts. This episode, we’ll do the high level stuff, the bishops and the pope, and then we’ll get local in part two. Probably talk a little bit about monasticism next time too. Good plan?

I take your silence as consent, as always.

One quick declaration before diving back in: I usually do my best to use a reasonable balance of sources when putting together an episode, but in this case I have relied heavily on Christendom: The Triumph of a Religion, by Peter Heather. It came out in 2022 and so is a solid summary of the most recent research into the early church, both intellectually and physically. Seriously, it’s a doorstop, but also engaging, clear, and thorough, as Peter Heather usually is. A lot of newer research has challenged the traditional narrative that the Catholic church represented a continuity with the Roman empire. Instead the modern scholars Heather summarizes along with his own view have come to see the period after 476 as a time of profound change in the church, as it was everywhere else. So, let that serve as both a disclaimer and a book recommendation.

To know where you’re going, you first have to know where you’ve been. Is that actually true? I hope so, otherwise there’s no point in spending your time doing history podcasts. Anyway, to start a discussion about how the church changed after the fall of empire, we need to establish what the church was like before the fall of empire.

Ever since Constantine had made Christianity the official religion of the Roman empire, emperors had seen it as their job to ensure that the church was as well run as any part of the state apparatus. The ideological base on which the whole concept of imperial power had always been that emperors were chosen directly by the divine, and that their status was confirmed by military success. That ideology barely budged with the transition from pagan to Christian. Following that logic then, the emperor was obviously the head of the church as he was the head of every other hierarchy, who could argue otherwise?

Constantine certainly took this view, and shaped the form that imperial leadership would take. He was a man with an eye for detail and saw himself in very exalted terms. All the factions and arguing between the bishops about the nature of Christ and the relative positions of the trinity had been tolerable before the emperor’s name was attached to it. Now, though, all the arguments reflected poorly on the emperor. He was the chosen representative of God, he should have control over his church just as he had control over his army. Unity had to be imposed, divisions had to be resolved, and Constantine called the first Council of Nicaea to resolve them.

I’m not going to hash out the conclusions of Nicaea again or any of the councils that followed it, the point for today is they were called by the emperor. Their agendas were largely set by the emperor, and their final conclusions had to be approved by the emperor. Probably equally important, they were mainly funded by the emperor. Nobody else could have afforded to subsidise the lodging of several hundred bishops and their staff, not to mention the cost of travel.

So what happened when the emperor suddenly wasn’t around anymore?

Actually western bishops had largely been absent from the great councils of the past. They sent observers, at times the bishop of Rome would send his views on the issues of the moment in written form, to be read into the record. Conciliar decisions took time to percolate to the outer edges of the empire, but their authority was recognized, as was that of the emperor.

When the empire was no longer present, however, the ties were weakened. Communication was harder, the bishops no longer had the emperor to act as final arbiter in any disputes. They could and did write to him, but the kings who were now in charge would really prefer they not involve him in the daily affairs of the new kingdoms, thank you very much. But decisions had to be made and disputes still had to be settled, so Church councils began to be organized on a kingdom-by-kingdom basis. Travel was still expensive of course, the basic verities hadn’t changed, so it was the kings who funded these councils. The bishops were integral to the running of the kingdom, so he stumped up. And by doing so, the kings took on some of that imperial authority. Now it was they who called councils, sometimes attending them, sometimes not. They set agendas and determined outcomes, often before the council even convened. These mainly dealt with more local matters, such as the behavior of bishops themselves, or details of practice, but they did make changes to canon law within the kingdom, and so the practice of the regional churches gradually drifted apart from each other.

We start to see more and more local gatherings of this kind as time passes, with meetings of the Frankish church occurring regularly throughout the sixth century. Clovis called the council of Orleans in 511, there was the Synod of Paris in 573, called by Guntram and another in 577 called by Childperic, also in Paris. That second one is the one which gave Bishop Praetextatus so much trouble. This wasn’t solely a Frankish phenomenon, the bishops of the Visigothic Kingdom met regularly, almost always in Toledo, their most famous meeting being the one called by King Reccared in 589 where he officially converted the kingdom to Catholic Christianity and consigned Arianism to the dustbin of history.

All these councils were aware of each other, bishops communicated with each other regularly, and generally tried to keep themselves facing in the same direction, especially when it came to doctrine. Even so, by increments, the church establishments were drifting gradually apart. At the same time, the role of bishops was becoming more defined. This period of church history, by the way, sometimes goes by a name: the Conciliar Era.

There has been a tradition that characterized the Church as simply a continuation of the Roman empire’s administration in a different form. I may have been guilty of promulgating that tradition myself, though I’m not going back through my scripts to know for sure.By implication then, the pope is sometimes seen as sliding smoothly into the hole left behind by the emperor.

As we’ve already seen, that was absolutely not the case. Just a couple episodes ago we talked about how large the imperial government had become, and how very puny was the church in comparison. The bishops never could have assumed all the responsibilities of the empire, even if they had wanted to. In the early days following his official conversion, Constantine had actually envisioned a significant and much expanded role for bishops in the provincial bureaucracy, with administrative and judicial responsibilities. It didn’t work, the bishops didn’t have the time or the training to handle the work. Later on, after more of the classically trained Roman aristocracy had moved into the diocese, it may have worked, but by then the moment had passed. When the empire disappeared, bishops did often take over municipal responsibilities, especially what we might call the social safety net. A bishop, though, had nowhere near the coercive power of enforcement that any government needs to function. That power belonged, wholly and completely, to the new kings

In principle, new bishops were elected by local clergy and consecrated by other bishops, the consecration intended to maintain an unbroken line of succession back to the Apostles. In practice, though, the choosing part often fell to the kings. Candidates would be proposed by the clergy, but it was absolutely clear and understood that a candidate without royal support would find it very difficult to assume their position. It was absolutely commonplace for the candidates proposed by the local community to have been “suggested” by the king. Any convocation that installed a bishop against a king’s wishes would find themselves at the sharp end of the royal displeasure.

In addition to the obvious advantage to kings to have loyal bishops in his kingdom, the positions were an irresistible form of patronage. The diocese, just like the estates of magnates, came along with a package of land, the produce of which supported Church operations, and kept the bishop in appropriate magnificence. You may remember I mentioned Bishop Felix of Nantes, whose favorite estate included 3,000 hectares of vineyard and farms along the banks of the Loire. The income from that spread, along with the other estates in the cathedral’s portfolio, would be split four ways, with equal shares going to maintaining the fabric of the building and its vestments, the clergy, the poor, and the remaining quarter to the bishop himself. That was the tradition in Francia, in the Visigothic kingdoms, income was split three ways, with the poor dependent on the generosity of clergy and bishop. The point of all of that is one that I’ve made before: a bishopric was a major financial windfall. Some were richer than others, but all were attractive and competition for them was intense.

It shouldn’t be too surprising then, that kings would often grant bishoprics as rewards to their favored nobles. It was an especially handy reward for kings to have available, since it didn’t require the king to give away any of his own land.

The practice opened bishops up to criticism in two ways. The first is probably pretty obvious; plenty of the nobles made bishops saw no reason for their lifestyles to change. They carried on feasting, drinking, hunting, and sometimes even riding to war. The more fastidious bishops and metropolitans deeply disapproved, and councils attempted to curb this kind of behavior, with limited success. The second problem was less obvious, but possibly more insidious. The culture of the Franks, and of pretty much everyone else, really, was a gifting culture. It was alluded to in the story of Praetextatus. Your king has given you this wonderful collection of lands and honors, it’s expected that you will give him a gift in return. Mutual gift giving was one of the sinews of social relations, and of a fair proportion of the economy. But where is the line between offering a gift in gratitude, and buying a bishopric? Simony, the purchase of church positions, was anathema to church leaders. It’s named, by the way, after Simon Magus, who in the Acts of the Apostles offered Peter and John cash in exchange for their powers of healing. Peter cursed him, “For I see that you are in the gall of bitterness, and in the chains of wickedness.” (Acts 8:14-24)

The simony problem would dog the church for centuries. It would, in a few hundred years, become one of the hinges on which church reforms would swing, reforms that would end with the supremacy of the pope and the creation of the medieval church that lives in the popular imagination. In our period though, the pontiff was, comparatively, nowhere, in spite of the popes’ own pronouncements.

The bishop of Rome was the most prestigious of all the western prelates, that much was agreed by everyone. That prestige was founded on a few foundation stones. First, there was the connection to the city of Rome itself; the city’s Christian community was the largest in the west from the beginning. Emotionally, Roma aeterna still had a special place in the hearts of the upper classes. That was enhanced by its status as the site of martyrdom of Peter and Paul, two apostles. That was, as the popes would occasionally point out, one hundred percent more apostles than any of the other patriarchs could claim. Guardianship of the two saints’ relics brought further kudos. But the biggest, most massive foundation stone for papal authority was, and still is, the principle of Petrine primacy. In this formulation, Peter was the foremost of Christ’s disciples, as confirmed out of Jesus’ mouth the Gospel of Matthew: “And I tell you, you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church, and the gates of Hades will not prevail against it. I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven, and whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven.” (16:18-19) Peter was the foremost disciple, the popes reasoned, therefore his apostolic successor, in an unbroken chain of consecration from the apostle himself, must also be the foremost bishop, and inheritor of all of Peter’s authority and powers.

The thing is though, prestige is not the same thing as power. The bishop of Rome’s assertions were all very well, but they had little practical effect. For one thing, other bishops pointed out, there was no scriptural evidence that they could find to support the idea that the powers Christ had conferred on Peter actually were passed along with the succession. And if they were, they were not possessed by all the bishops collectively. The general opinion was that among the five patriarchs of the Christian Church (Rome, Constantinople, Antioch, Alexandria, and Jerusalem), Rome was to be respected, even acknowledged as first amongst equals, but deferred to without question? Nah.

That attitude pretty much prevailed amongst the lesser bishops of the west as well.

Popes kicked against this attitude periodically. Beginning with Innocent I (401-417) the popes’ response began to come in the form of the decretal. A decretal is a formula for responding to a query from a correspondent. The response was written on the same scroll, below the original request. The thing about decretals was that they were the standard form for communications from the emperor to governors and other bureaucrats. The implication from Innocent and those that followed him was that these decisions were legally binding. Leo I (440-461) built on the idea by claiming the right to act as a court of appeal for western bishops, and to bestow the badges of office (the pallium) on archbishops. In 445, Valentinian III was even prevailed upon to give legal force to these papal assertions, declaring that “if the authority of the Apostolic See has sanctioned or should sanction anything , such regulation shall be as law.”

After the disappearance of imperial authority from Italy, the effort was stepped up. Pope Gelasius (492-496) was especially bolshy. In 496 he wrote to emperor Anastasius: “There are two powers which for the most part control this world, the sacred authority of priests and the might of kings. Of these two the office of the priests is the greater in as much as they must give account even for kings to the Lord at the divine judgement… You must know therefore that you are dependent upon their decisions and they will not submit to your will.” That was a wild claim, and completely contrary to the ideology that had governed the church up to that point. Essentially Gelasius was creating what we would call the secular sphere, entirely separate from the sacred, and pushing the emperor into it.

In the sixth century, a scholar by the name of Dionysius Exiguus labored to bring together a collection of canon law, compiled with great effort the rulings of ecumenical and regional councils, along with all the papal decretals that could be found. In his commentary Dionysius Exiguus made the assertion that papal decretals were as authoritative as the rulings of ecumenical councils. He also was the first to propose the anno domini system of dating, though it would be a while before it became popular. Fun fact.

So all of those 350-odd words seem like the opposite of what I’m claiming. It all sounds like exactly the kind of supreme authority that the popes of the high middle ages claimed. And let me tell you, those later popes absolutely used all of these points to make their case for that authority. But there are problems with that conclusion.

Starting with decretals. Dionysius Exiguus was a careful researcher, and for the first 120 years covered by his compilation, he found only 41 decretals had been issued. That’s an average of about one for every three years. For comparison, in the 12th century, the papal see was issuing 30 per year, ten times as many. Decretals were written in response to queries from other bishops, and other bishops just weren’t asking much. Nor did the popes have any kind of apparatus to go out and find issues to resolve, there was no system of papal representation outside his own metropolitan territory of the South of Italy and Sicily.

Gelasius’ letter had come at a very specific time, after the Ostrogoths had established themselves in Italy, and during the Acacian Schism. That’s an episode that I’ve often thought about re-writing, but now is very much not the time. The point is that Gelasius was in a safe position from which to needle the emperor without fear of immediate retaliation. Once Belisarius had recaptured Rome, Gelasius’ letter sank without a trace, and popes once again came under the sway of the emperor. At one point, three Greek-speaking popes in a row were installed by Constantinople, so complete was the imperial hold over the office. Gelasius’ letter would be dug out again in the 12th century, and quoted in every work of canon law from then on, but in the decades after 530, it was pretty much entirely forgotten.

And just to tie up loose ends, that declaration by Valentinian III? Valentinian was a remarkably weak ruler, and that would not be the only of his declarations that ultimately left no mark on the course of immediate events. We can put that edict aside as irrelevant. Harsh, but true. Popes really really really wanted to be the arbiters of western Christendom, but in the sixth, and seventh, and most of the eighth centuries, the rest of western Christendom was content to listen politely, thank him for the input, and get on doing whatever they were going to do anyway.

The attitude of the provinces is summed up by a letter written in 648 by bishop Braulio of Zaragoza to pope Honorius. The pope had taken issue with what he saw as the Visigothic bishops’ failure to enforce discipline amongst the clergy and correct episcopal abuses. Braulio wrote on behalf of all the bishops gathered for the sixth council of Toledo, and they were disinclined to accept the Pope’s criticism: “We did censor transgressors, and we did not keep silent when it was our duty to preach. Lest your apostolic highness think that we are producing this to excuse ourselves and not for the sake of truth, we have deemed it necessary to send you the previous decrees along with the present canons.” The whole thing is very recognizably in the tone of “per my last email”, and Braulio closed by pointing out that the verses that Honorius had used to support his arguments were from Isaiah, not Ezekiel as the Pope had said. All in the most diplomatic, careful language, but the overall message: you do your job and let us do ours, is as plain as day.

I have talked for too long, and if I keep going this is going to become another record breaker. So I’ll leave the religion of the common folk until next time, along with some talk of monasteries and such. Honestly, there’s so much to talk about it could swallow the whole podcast, but I’m pretty sure you’d all abandon me. So to close today, let me just finish us off with the story of bishop Praetextatus.

The unfortunate bishop spent several years on Jersey, until 584, when Chilperic died. He lobbied king Guntram to review his case, and to be restored to his old job as bishop of Rouen. Guntram agreed and heard evidence from interested parties. One of those parties was queen Fredegund, who Gregory partially blamed for bringing the prosecution in the first place, but she was overridden, and Praetextatus returned to Rouen. He had spent his time in exile writing prayers and poetry, as you do, and shared them with his colleagues at a council in Macon, to mixed reviews. In 586, Praetextatus had a sharp argument with queen Fredegund, a “bitter exchange of words”, as Gregory put it. “She told him that the time would come when he would have to return to the exile from which he had been recalled. ‘In exile and out of exile, I have always been a Bishop,’ replied Praetextatus, ‘but you will not always enjoy royal power…when you give up your role as Queen you will be plunged into the abyss…’ The queen bore his words ill.” A while later, during Easter services, Praetextatus was stabbed and wounded by an assassin. He was carried to his bed, but it was clear the wound was mortal. Fredegund came to visit the dying man and expressed horror that such a thing should have happened. Praetextatus was having none of it, and accused her directly of both his own murder and many others. He refused the doctors that the queen offered him, and before dying, cursed Fredegund and promised divine retribution. This confrontation has appeared in art, one painting by Lawrence Alma-Tadema,reminds me of the death of Socrates, though its emotional tenor is very different. I’ll put it on instagram.

I have talked long enough. Come back next time, so I can yap at you some more. We’ll talk about the problem the church faced in carrying its message to the rural peasants who made up more than 90% of the population, and about the actual experience of attending church in the time of Gregory of Tours. Until then, thank you for listening, and look for the show on instagram @darkagespod. Take care.