This episode is a continuation of last time’s discussion of the sixth century church. Last time was the high level stuff, the relationships between bishops, kings, emperors, and popes. We found that the popes generally had a high opinion of their authority, but that it wasn’t an assessment that was generally shared across Christendom, and that the kings of had moved in to at least partly take over the role of the emperor in the management of the church and the calling and management of governing councils. Today is going to be a little bit more grassroots.

By 476, the elites of the Roman empire had pretty much all turned to Christianity, some through genuine conviction, some through a recognition that not doing so would be career-limiting in the new Constantinian world. But what about everyone else? When we talk about the glories and luxuries of the Roman World, we are usually talking about the top ten percent of the population, economically speaking. The vast vast vast majority of Roman citizens, especially in the west, were rural peasants of one kind or another. Unless they joined the army, just about everyone would have lived and died within a few miles of where they were born, and only had contact with the glories of elite culture and education when they went to pay their taxes and respects at the villa of their local patron or employer.

By the end of the fifth century, it’s likely that these people’s understanding of the new religion was partial at best. But Christianity was for everyone, and the peasantry’s souls needed saving just as much as did the magistrate’s. Bishops worked to bring the masses into the fold, and alongside them other actors, namely monasteries and secular lords, worked toward the same goal, sometimes to the bishops’ irritation. Today will be the story of how the rural people were brought to the faith, and how the faith was changed by that process.

Much like last time, I need to begin by going backward a bit.

Christianity’s heartland was in the east. Communities of Christians had existed and grown there since the time of the Apostles. Most of the great intellectual exponents of the faith lived and worked in the east. The great ideological struggles of the early church were most intense in the East. And four of the five patriarchs – Jerusalem, Alexandria, Antioch, and Constantinople – were in the East. Its long history meant that Christianity had begun to penetrate all levels of society by the time of the late empire. A quirk of geography played a role in the administrative structure of the early church in the east and aided the conversion process. In the eastern parts of the empire and along the Mediterranean littoral, the climate tends to be semi arid and/or mountainous, and fertile land appears in concentrated pockets in valleys and along the coasts. That encouraged the development of compact areas of settlement, with population centers supported by a relatively limited hinterland, and with political organizations that developed to match; i.e. city states. The poleis in the Greek-speaking east, various kinds of civitates in the Latin west. The civitas became the basic unit of administration in the Roman empire, and referred to both the urban center and the rural lands that supported it.

The Christian church that grew up in that environment was organized in patterns that meshed with this geography. The community in each civitas was overseen by a bishop (the word comes from the greek episkopos “overseer”) who worked alongside priests, or presbyters (from the Greek presbyteros “elder”) to perform the eucharist and other liturgical rituals. Importantly, though, by the fourth century it was established that only bishops would preach. In a world where population was mostly concentrated in dense pockets, it was relatively simple for this structure to provide pastoral care and education for their communities. Congregations could easily gather in a central location to hear preaching, receive baptism, and observe the eucharist. Christianity, in the first centuries, was thus a largely urban phenomenon, in both east and west.

The broader geography of the west, though, was significantly different, especially in Gaul and Britain. Outside the Mediterranean fringe, fertile land was much more widely distributed, and things were much more rural, economic activity was spread out among more isolated farmsteads and villas. Cities were smaller and further apart, and so the civitates of the west were physically much larger than in the west. The model of one bishop, one civitas that had prevailed in the east was imported to the west, but geography put strains on the system. To put numbers on it, in 400 North Africa was host to more than 600 bishoprics; there were only 118 in Gaul, most of them in the south, with correspondingly larger territories under their jurisdiction. It was a logistical problem, and in spite of the patronizing tone most church leaders took when describing the country people, it was nevertheless their duty to save every soul that they could within their sees.

The actual details of the religious ecosystem of the countryside are actually pretty difficult to determine with any precision. It is clear from bishops’ accounts and the rulings of church councils that it was still very much a work in progress by the time of Gregory of Tours. The writers most useful to historians are those of Gregory of course, writing in the middle to late 500s, Caesarius of Arles, in the early 500s, and Martin of Braga in the late 500s. All three complain about the need to stamp out similar lists of incorrect practice. These were things like rituals of divination, rituals intended to safeguard crops or health, making and distributing amulets, leaving offerings at places of supposed supernatural power like groves, crossroads, or springs. The formal network of pagan priests, with temples and organized sacrifices, had largely gone, but the country folk had long memories. Many attempted to syncretize the old ways with the new. Caesarius references baptized Christians who refused to work on Thursday because it was Jupiter’s day, for example. Martin of Braga refers to invocations of Minerva while weaving, references to numerology to determine the best day to undertake a journey, the muttering of spells while compounding herbs for remedies, and condemns all such practices. He is especially scathing to those who continue in these habits after having been baptized; “Why then did these miserable people come to church? Why did they receive the sacrament of baptism, if afterwards they intended to return to the profanations of idols?”.

The common thread that runs through that list of practices that bishops found objectionable is the survival of a transactional attitude to religion. We saw this in the story of Clovis’ conversion, where he proclaimed, when a battle was not going well, that if the Christian God delivered victory, then Clovis would consent to be baptized. That is not an uncommon theme in the conversion stories of northern warrior kings. This attitude was very much a part of pagan practice. Anyone with even a passing knowledge of Greek myths knows this. The old gods and goddesses were not omniscient, transcendent beings, they were not even necessarily morally good or bad, they were simply beings that were more powerful than humans, and could be bargained with. Their attention could be attracted and their help secured by human actions like prayers, offerings, and sacrifices. The Christian conception of God is of an entirely different nature. The idea that a Transcendent and Omniscient God could be influenced by gifts, like some corrupt magistrate, was ludicrous to the minds of the Church fathers, especially Augustine of Hippo. It was a habit that died hard among the population though.

The word most often used at the time to describe the people of the country was rustici, rustics (Peter Heather suggests that “yokel” might best capture the spirit of the Latin term). Over the course of the sixth and seventh century the abstract form, rusticus, came to be synonymous with incorrect christian practices. Peasant religion, even if nominally Christian, needed correction, guidance, and sometimes a good firm whack with a stick if the country people were to be brought fully into the true faith.

Education was key, obviously, and given that the peasantry was pretty much 100% illiterate, that education would have to come through imagery, and preaching. So we are right back to the bishops’ logistical problems.

Small churches had begun to spread into the countryside by the 520s, staffed by priests who could perform ritual services, manage almsgiving, but not preach. These networks of churches were under the direct control of bishops and were endowed with their own lands to support them. The extent of the networks is hard to determine, the evidence is patchy at best. By the time Greogry was writing, there were 24 establishments in his territory of the Touraine. That made it much easier for peasants to access services, but didn’t necessarily improve access to preaching. Sermons could only be heard at whichever church the bishop was holding services in, and not all bishops preached every Sunday. That finally began to change with the Council of Vaison in 529. Caesarius prevailed upon his fellow bishops to allow priests to deliver sermons. This massively increased the number of congregations to whom instruction could be delivered, obviously. However, given that only 12 bishops attended the Council of Vaison, the idea took some time to spread. It took a hundred years for the idea to be made standard practice in the Visigothic kingdom, for example.

What would these newly empowered priests talk about, then? In the fourth century, St Ambrose had discoursed from his cathedral in Milan in elegant language and rhetoric in the finest traditions of Classical Roman education. That kind of thing would not fly in the provinces. There was no guarantee that congregations would stay for sermons even if they were available. Caesarius was notorious for locking the church doors after his flock had filed in so they could not slip out before he’d delivered his address. Obviously these were the days before fire marshals.

Caesarius worked to make sure that his sermons would be relevant and worth listening to, and to help his priests do the same. He produced a collection of sermons for the benefit of both bishops and priests, collected some of his own preaching, and adapted some sermons of Augustine of Hippo. All delivered in simple, unambitious Latin that would be comprehensible to its audience. It was very influential, and other collections began to appear at the same time. All emphasized simplicity in both language and concept. Other collections, like Gregory’s miracle stories (our boy Gregory was prolific well beyond the history we’ve been talking about constantly), could function as the seeds for sermons as well. Each story is short and easily digestible, with a clear demonstration of correct Christian action. Through these stories and the sermons of the priests, the broader population could be brought to an understanding of what it meant to live a good Christian life.

So, what did it mean to live a good Christian life?

Baptism was central. In the days of the early church, baptism was the culmination of a process of education and exorcism that could take years. By the sixth century, twenty days was the recommended maximum. If you’ll allow me a potentially offensive analogy, it reminds me of early Communists who won proletarian converts one by one through intense education in economics and political theory. It was good, thorough, and would eventually bring about the revolution … in 10,000 years or so. We all listened to Mike Duncan, right? In order to become a mass movement, the process needed to be speeded up. It was the same for baptism, to reach the greatest number of souls possible, the barriers to baptism had to be lowered, and they duly were.

After that, education focused on memorizing, being able to recite, and have some understanding, of the Apostle’s creed, a simplified version of the Nicene creed – the central affirmation of Christian faith and orthodoxy. It focuses more on the narrative of Jesus’ life and ministry, rather than the more complex theological points emphasized in the Nicene creed, which had been developed at least partly as a bulwark against the Arian and other heresies.

The Christian message being carried out into the countryside was fairly straightforward, and I quote Peter Heather’s summary: “Christ’s Incarnation and Resurrection had freed Christian believers from enslavement to the devil and opened the prospect of eternal life. In this world, meanwhile, the good Christian should attend church regularly, as well as avoiding theft, fornication, adultery, and murder.” There was more to it, of course; the church’s ongoing discomfort with sexuality led to attempts to regulate sex even within marriage, for example, but that was, essentially, the deal.

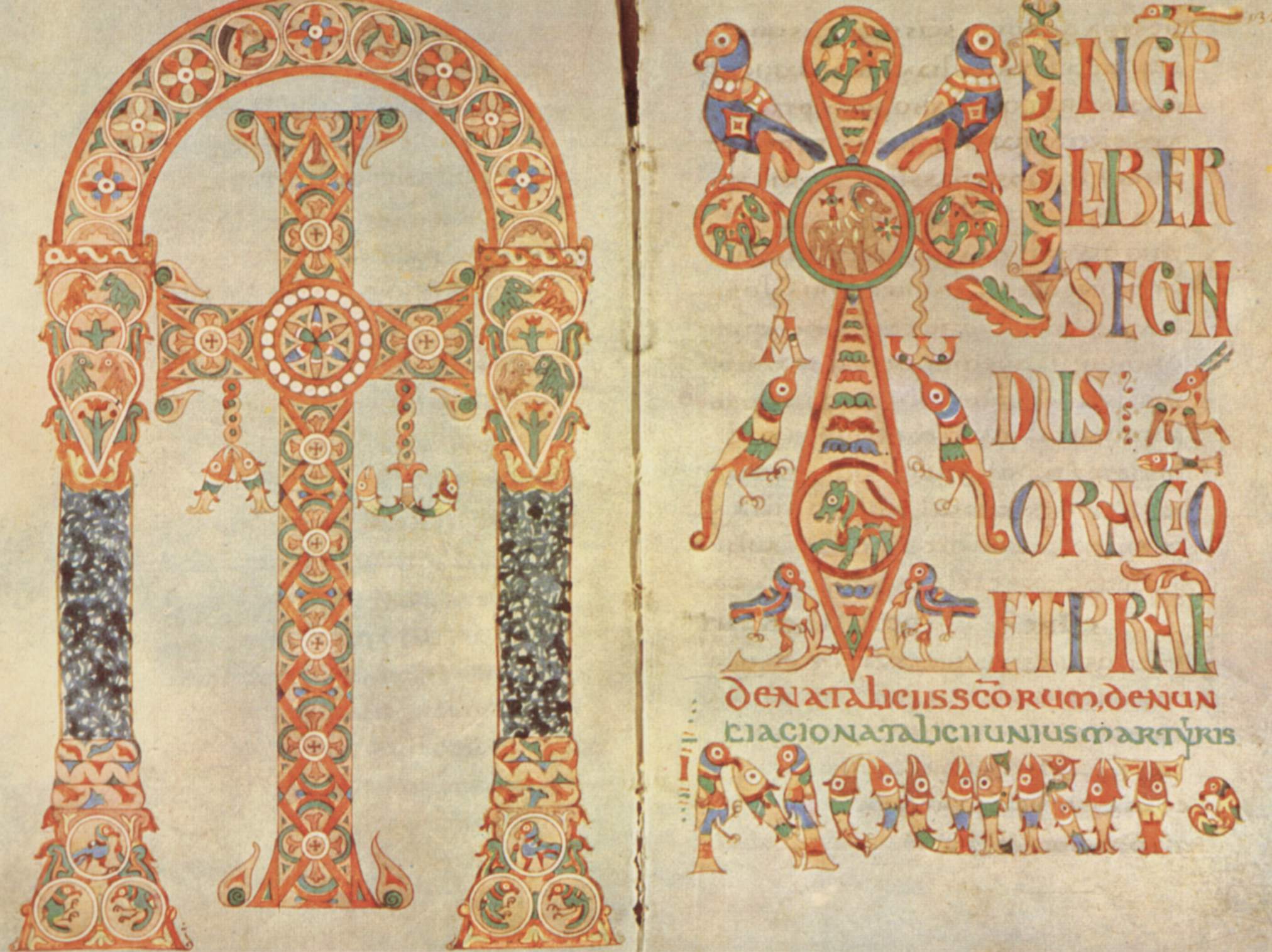

What’s missing from this message is any real attempt to foster the kind of intense, personal, and occasionally frightening spirituality that would be characteristic of the later middle ages. The focus, even at Easter, was not on Christ’s passion, but on the good news of the resurrection. In art, Jesus was almost always presented as Christ the king, often in imperial regalia or enthroned in heaven, not as the victim of torture and execution. The image of the crucifix would not become common until the tenth and eleventh century.

Yann Gwilhoù, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The church was aware that it had to meet its new audience mainly on its own terms. Conversions of convenience or based on fear would always be shallow and easily reversed if circumstances changed. So it adapted itself to fit into the rhythms of life as easily as possible. The process of transformation from underground movement to mass religion had been ongoing since the third and fourth centuries, accelerated by imperial approval. Part of the process was the transition from pagan to Chirstian festivals. Christmas was set to coincide with the new-year celebrations of the Kalends of January and Saturnalia. The deep bench of Martyrs was mobilized, with their feast days being promoted as alternatives to the previously established festivals that marked the pagan year. Today, this process is frequently, and glibly described by many as Christianity “stealing” these festivals. That is, to be blunt, a shallow and dismissive understanding of the process. Throughout its history the great talent of Christianity has been its ability to adapt to the new environments and social settings. Christmas, Michaelmas, and the like, were advanced as alternatives to Christians who found themselves isolated from the festivals that had previously marked the progress of their lives. The goal was to minimize the dislocation felt by converts who found themselves uncomfortable with the celebrations of their neighbors, by offering an alternative. The church was involved in a dialogue with the world that had existed prior to itself. It shaped itself and its message in response to the needs of its audience, in parallel to its efforts to shape the attitudes of that audience. It was a deliberate policy, but not a centrally directed one, as bishops responded to local circumstances.

Isere-culture, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

All of this sounds like an admirable effort by the bishops, and no doubt it was. But there is some doubt as to how effective it all really was. The efforts to remove the transactional attitude from Christian worship met with limited success. Caesarius of Arles and before him Augustine of Hippo had scoffed at the idea that human action could change the mind or affect the behavior of God, but the patterns of belief among the laity seems to have retained much of that idea. Correct religious action could shape outcomes, by persuading the supernatural to act one way rather than another. If you listened to the bonus episode about St Macarius, lo these many moons ago, you may remember that Christian monks were as likely to be practitioners of magic as were pagan priests. Amulets remained pretty much ubiquitous, with the names of saints and angels and biblical inscriptions replacing invocations of gods and spirits. The full range was put to work, talismans, incantations, and offerings. Caesarius in particular railed against this kind of thing, and worked hard to suppress it. Christians should be focussed, as he believed the Almighty was, on the fate of their souls in the next life, not on the relatively petty concerns of this one.

He largely failed. Even the well-educated leaders of the church could not be entirely focused on the hereafter. Gregory of Tours relates how he used a recipe found in the book of Tobias to cure his father’s gout, and always wore an amulet to ward off migraines. Miracle stories and Saints’ Lives are stuffed with examples of the simple one to one equation, proper worship and action would lead to desirable outcomes in the here and now, as well as in the hereafter. Conversely, rusticitas would lead to negative ones. These arguments were, in their essence, arguments for a Christian magic more powerful than the old pagan rituals. The saints were available, in shrines that were spreading across the countryside, to provide a focus for such actions and petitions, and that was a good thing, since even by Gregory’s time, 250 years after Constantine’s conversion, anything resembling what we might call parish churches were hard to come by.

Even with twenty-four churches in the Touraine, a peasant of Gregory’s see would still, on average, have had a 6 mile walk to the nearest church. Hundreds of churches were being built, but it would take thousands to achieve the kind of saturation that was really necessary. It’s doubtful that most peasants attended church every Sunday, not with four or five hours of walking required. A council held in 506 at Agde is probably a good indicator of the reality, requiring that Christians must attend one of the bishop’s Churches at least at Easter, Christmas, and a handful of other major festivals. Even that was unlikely to convince the old, the sick, or the busy, to take the long walk. The twice-a-year churchgoer is far from a modern phenomenon.

But there were other venues for religious services available, besides the churches under episcopal supervision, and both had the potential to be troubling to bishops. There were private churches, erected and endowed by landowners, and there were abbeys and monasteries. A full discussion of monasticism deserves its own episode, so I’ll just hit a few relevant points here. In the early Merovingian period, inmates were more likely to be from the elite strata of society, and institutions did not generally see it as their mission to educate or minister to the general public. Bishops were concerned that they would become alternative loci of influence with nobles and kings. There were also the unregulated institutions that grew up around wandering ascetics and missionaries, many of them from Ireland. These fell outside episcopal regulation and could become very popular with both nobles and peasantry. Saint Columbanus established a monastery at Luxeuil, for example, which brought him into direct conflict with Brunhilda, who saw him as a competitor for influence with her Grandson Theuderic, and saw him eventually driven out. The intitution had been set up on the former site of a pagan shrine.

As an aside, Luxeuil has to be among the top ten most French of all French place names, and if you don’t know how it’s spelled … whatever you’re guessing right now is wrong. Anyway.

Institutions set up by Irish missionaries were doubly problematic for the bishops of the Continent since they followed the Celtic rite in their liturgy and practice. A deep pit of digression yawns at my feet here, and I must maintain my own writing discipline. So I’ll just say that the Celtic rite differed from the mainstream, or Roman, rite in a number of ways that made it unacceptable for bishops of Francia and Italy. These included marriage practices, the method for calculating the date of Easter, they even found the Irish form of tonsure weird. Really, both the Irish church and the development of monasticism deserve much fuller treatment than I’m giving them here, and they are on the future episode list, so allow me to just move on for now to the phenomenon of private churches.

I’ve gone on and on about the rewards that kings used to maintain the loyalty of their fighting men. Sometimes those rewards were physical treasure, gold and silver and so on, but more often, especially on the continent, they took the form of land grants. Land was king, in an almost entirely agrarian economy, land was the absolute bedrock of wealth, and unlike cash payments, it produced income in perpetuity. Agricultural production depended on labor, land was useless with no one to work it, and the grant of an estate usually included the people who lived and worked on it. There were still plenty of independent farmers in Francia, but the estates granted to the kings’ followers were usually worked by tenant farmers or servile peasants who either paid rent in kind or owed labor to the lord. The legal status of these, called coloni or limitanei, varied. The completely bound serf of later feudalism has not yet arrived, but coloni still had much fewer rights than their free-holding brethren.

From early on, bishops had encouraged landowners to build churches on their estates as part of their efforts to carry the gospel to every class of society. John Chrysostom, the patriarch of Constantinople from 398 to 404, had preached to his elite urban audience: “Many people have villages and estates and pay no attention to them and do not communicate with them, but do give close attention to how the baths are working … not to the harvest of souls … Should not everyone build a church? Should he not get a teacher to instruct the congregation? Should he not above all else see to it that all are Christian?” In the west, about the same time, Maximus of Turin said, “It is not right that you who have Christ in your hearts, should have Antichrist in your houses, that your men should honor the devil in his shrines while you pray to God in church.”

Many landowners took up the call with sincere piety. Others could see upsides to the idea that were less spiritual. Having the whole labor force remain on the estate on Sundays, rather than traipsing off to the nearest bishop’s church, helped landlords maintain control over these populations. A piece of the estate was granted to support the church and its mission, and landowners felt entitled to set conditions on those grants. Sometimes they would claim a portion of the tithes that were paid by the congregation, just a little extra revenue captured there. And usually the landlord insisted on the right to appoint the priest. It put the priest firmly in the landowner’s pocket, a useful mouthpiece for the boss. That was a practice of which bishops would come to deeply disapprove. More often than not, the priest would be selected from among the estate’s peasants. Education would be limited if not non-existent, and the cleric’s loyalty was firmly directed toward his landlord and patron, rather than to the local episcopate. It all added up to a level of control over church affairs by secular authorities that bishops, and later popes, would come to resent and work hard to break. But those efforts lay in the future.

Alongside all these gentler strategies of pastoral care, education, improved access, there was a more frankly coercive element to the Christianization of the countryside. If peasants could not be brought to the faithe by persuasion or by social pressure, other methods were available. Pope Gregory I urged the landlords of Sicily to raise the rents of non-Christian tenants until they converted. If all else failed, both Caesarius of Arles and Isidore of Seville agreed that Christianity could be beaten into the especially stubborn. The Hispanic bishops at the Third Council of Toledo (589) agreed, and charged both priests and lay magistrates with a duty to eradicate idolatry by any means necessary, short of murder. Those that failed to do so were to be excommunicated.

And yet in 598, Pope Gregory wrote to the bishop of Terracina, disturbed by reports that people in his see were worshiping and making offerings to sacred trees. Terracina is 35 miles from Rome, the very heart of Western Christendom. It lies on the Appian way, the famous highway between Rome and Naples, not an out of the way backwater. And yet even there, old habits died very hard.

More than anything, the impression I want you all to take away with you is that the process of Christianization was slow in the countryside. It advanced in fits and starts, hindered by the hard facts of geography and manpower, and by the general inertia of human habits and desire to hold onto traditional ways of life. Life for the agrarian poor was so precarious, so close to the edge of disaster, even in good times, that changing any habits that helped manage that uncertainty would have seemed deeply, deeply risky. And make no mistake, a change in ritual practice would have been seen by everyone involved as just as important, immediate, and material as a new tool or an altered field rotation. The stereotypical conservatism of country-folk does not come from nowhere. The steady drip of ecclesiastical pressure, more direct initiatives from the landlord class, gradually eroded the old ways and replaced them with the new. Let us also not forget the support that the church often provided to the destitute, especially in urban centers. That was a service that had been conspicuously lacking from most pre-christian religious practice – a failing that had been recognized by the Roman opponents of Christianity, actually. All of this combined to reshape the worldview of the populace, but again slowly.

So, now that we’ve covered all of that, what would going to church have been like, in Gregory of Tours’ time?

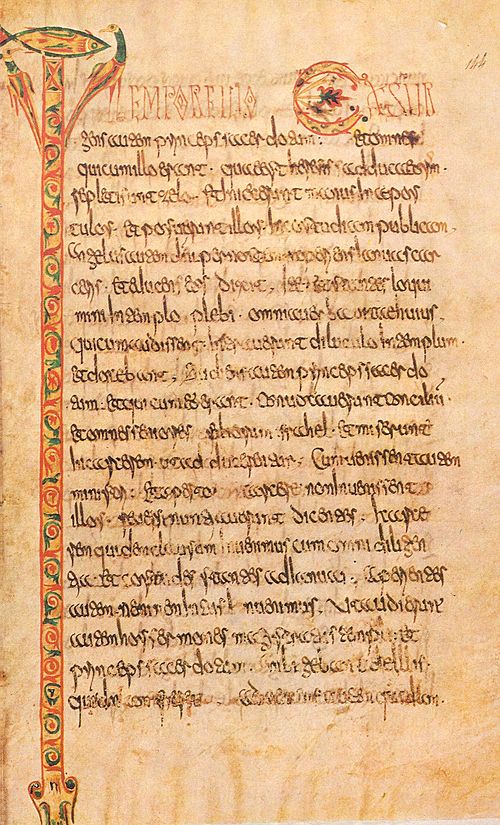

Detailed reconstructions of services are difficult at this early state. The congregation would have heard the recitation of prayers and the singing of psalms, and the central ritual, which was of course the Eucharist. Whether the entire congregation received communion, and whether they did so “in both kinds”, i.e. both the bread and the wine, is not clear. Later reforms suggest that they did not, some parishioners may have only shared communion at Easter, and often only the bread. It’s entirely possible that the congregation simply witnessed the ritual, the miraculous transformation of bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ, without directly participating. The priest’s blessing would have rounded out the service. If the church in question was being visited by the bishop or his cathedral priests, one might have heard a sermon, though that was not a given. It’s clear from the urgings of the likes of Caesarius that many bishops did not preach every week, and some may not have preached at all. Local variation in the depth and intensity of services was probably considerable. A barely literate peasant priest, who recited and sang by rote memorization, was probably considerably less inspiring than a Caesarius in full flow.

BnF Museum, CC BY-SA 3.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/, via Wikimedia Commons

All of this probably sounds like a fairly miserable and unenlightening experience, and I’m sorry if that’s the case. Without having been there, heard the chants, experienced the charisma of the priest, or lack thereof, felt the mood in the room, it’s impossible really to grasp an understanding of the experience. I’m not a religious person, but I have attended church services in a variety of denominational contexts and been moved by some, bored by others. It’s difficult, when reading or discussing the history of the Church, to really get that sense of very personal experience – I have an easier time imagining how I would feel in the midst of a medieval battle than in the midst of a medieval Church service. I think that’s partly because the emotions are simpler – the nexus of terror and rage – and partly because the details are missing. The fervor of the faithful comes through loud and clear in their writings, so intense that in some cases it actually makes it harder to understand their experience rather than easier, the feelings are just so alien to a modern secularist like me.

Music would probably have been a big part of the experience, as it is in most churches to this day, though unfortunately no fully notated musical settings survive from the time. The closest we can probably get is the Ambrosian chant, part of the Ambrosian rite of Catholic services still used today in and around Milan. It has existed alongside and been influenced by the other modes of church singing, so I’m not saying that this is one hundred percent what a sixth or seventh century church sounded like, but hopefully it gives a flavor.

How to sum all this up then. The main points to leave you with I think are these: the carrying of the christian message to the whole population of the empire was far from complete when that empire crumbled. In spite of considerable challenges, bishops worked hard to make services, both ritual and pastoral, available to all within their remit. They were helped in their efforts by an elite class that erected their own institutions, for both spiritual and secular reasons, and by monastic institutions that began to appear in greater numbers in the sixth century across Francia. The message carried out to the provinces was a message that had been tuned to its audience, and in the early days maintained a largely positive outlook, focussing on basic education and making the transition from pagan to Christian practice as easy as possible. When faced with intransigeance, though, both Church and temporal authorities were prepared to use coercive or punitive measures to ensure compliance. I would note, however, that that was a feature of the hierarchical society, which pre-existed the church, and not a strictly Christian innovation. The ruling classes were prepared to force compliance in non-religious areas with just as much violence as in religious ones. Indeed, on balance, the church probably was a moderating influence on the violence of lords and masters overall.

An element of the old ways survived, in patches, in folkways, in local superstitions that lingered long after the old Gods had been forgotten. There’s little to no evidence of any continuity of pagan practice that survives up to the modern day. The attitude that the supernatural could be called on, that actions could be taken to moderate the often cruel blows of nature and circumstance, remained. It found its way into Christian folk practice, sometimes to be roundly condemned by the episcopal authorities, sometimes to be adopted by them. The Church was, in those centuries, very much a top down affair, but it absorbed some of the culture that it encountered, and made itself stronger and more elastic in the process.

That’s all the religion i have for you for now, though, this being almost the middle ages, i’m sure it will come up again. Next time we’ll be heading back to Italy, for the first time in almost two years, would you believe. That’s for those of you listening in real time, if you’ve been binging, it’s probably been about a week, but still.

I do have a little bit of news before I go. I’ll be appearing on the Podbean Amplified podcast, talking a bit about this show and what I’ve learned about history and about podcasting. So if you’re interested in seeing what I sound like when I’m talking ex tempore, that episode should be dropping on the ninth of March, on Podbean Amplified. There is a video version that will appear on youtube and wherever else does that kind of thing, I don’t know that I recommend that. I close my eyes when I talk sometimes. It’s weird.

All that is left then is to thank you all for listening, and for your support. I read all the comments that appear on spotify, even if I don’t respond, and some of them are brilliant. Supporters in need of special thanks, because of their support on ko-fi.com, are Matt and the generous Don, along with beloved monthly supporters Jeff, Toasty, Muggy, Paul, Jesse, Dusty, John, Alex, Mr Jordan, Michaja, Barchester, and a big welcome to new monthly Tom.

Alright everyone, until next time, take care.