490ish to 526

A whirlwind tour around Europe, checking in on what’s been going on in the years up to Theodoric’s death.

Hello, and welcome to the Dark Ages Podcast. Todays episode: The Magical History Tour.

This episode is a kind of digest, a summary of events and changes all around Europe, aiming to have a more or less comprehensive picture of the situation around the time of Theodoric’s death in 526. In terms of listening time it’s a relatively short episode, but that just makes it more densely packed with information. So make sure that you take really good notes, there will be a test next week,, and if you don’t pass it you’re not allowed to listen to this show anymore. I’m kidding, of course, for real, keep listening. Please. And really, don’t worry too much about the names, the general picture is more important as a starting point. We will be entering a new phase going forward from here. By the end of this episode, fifty years will have passed since Romulus Augustulus was deposed, and the living memory of the western empire was disappearing. How people thought about it was changing, both in East and West, and the nature of its legacy would be decided in the coming decades.

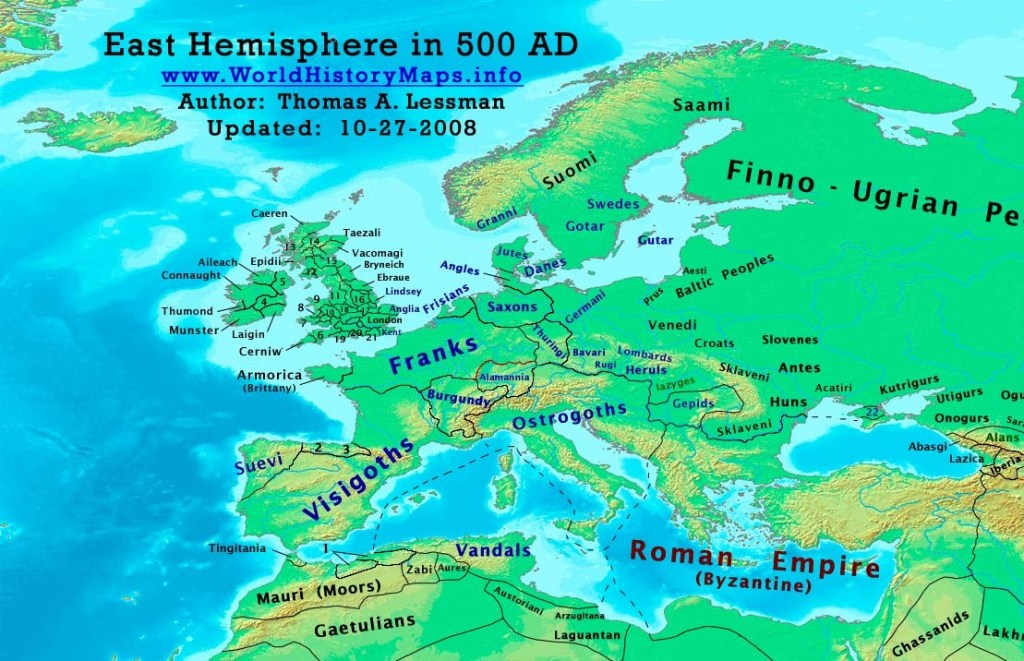

That’s for later though. Today’s show will start where we left last time, with the sons of Clovis, and Frankia. We’ll talk about Burgundy, then the Visigoths and Suevi in Spain. You forgot about the Suevi, didn’t you? It’s okay, everybody does. In a perfectly logical move, we’ll then hop over to the lands beyond the old frontiers, to Germany and the Danube basin. A quick check in with Constantinople will bring us up to date with what’s been happening over there. And then for reasons that I hope will soon become clear, we will finish up in Africa. I hope all your passports are up to date, it’s a lot of ground to cover, and there’s no point in dilly dallying. So let’s get going, and get the best possible start to a trip by heading to Paris, and check in with the sons of Clovis.

Gregory doesn’t have much to say about the Clotilde’s sons for the first decade after Clovis’ death. Only their half brother Theuderic attracts his attention, as he is forced to fight off an invasion from a people we haven’t heard from up to this point – the Danes. Actually we did hear about them back in the Nibelungenlied. This invasion was led by a king Gregory names Chlochelaich. It’s generally agreed that this is a Frankish translation of the name of a Danish king named Hygelac. If you’re an English lit major and that sounds familiar, that would be because Hygelac is Beowulf’s uncle, the king of the Geats, in that one poem, you know the one. Can’t think of the name right now. Fun fact: Hygelac was killed in the course of the raid, estimated to have taken place around 516, and his body left on the field due to the disordered retreat of the Danes. He was found by the Franks, and because of his incredible height, his corpse was displayed as a curiosity in Theuderic’s court for many years after.

Theuderic’s other exploit was the complete annexation of the lands of the Thuringians, in an episode that’s spookily similar to the Burgundian drama Clovis was involved in. The Thuringians consistently serve as dupes for the Franks in Gregory’s narrative, but they can’t have been complete non-entities. Theodoric courted them to secure his northern frontiers, and though they lived outside the boundaries of the Roman Empire, it’s possible that many of them were already Christians. Another significant section of their territory now fell under Frankish rule, and the reach of the Frankish empire (can we call it that?) reached a little further beyond the old limes of the Romans. Theudderic’s conquests were just a manifestation of the family business, as all four of Clovis’ sons expanded their territories in whatever direction opportunity presented. Sometimes they teamed up in pairs or trios, sometimes in solo operations. There’s a strong sense in the sources that their external wars were basically a way of sublimating their sibling rivalries and keeping civil war at bay. By dividing his realm as he did, Clovis put a centrifugal force in place that would be the Achilles heel of the Merovingian realms for most of their existence.

The Death of Clovis, coming as it did after the humbling of the Visigoths, left space for the Burgundians to rise in the power-rankings of Gaul. Their king Gundobad still officially held the Roman imperial title of magister militum, and when he died in 516 his son Sigismund successfully petitioned the emperor to inherit the honor, along with the rank of patrician. Religious drama dominated the Burgundian court for the next few years, as Sigismund was an enthusiastic convert of Catholicism. He convened a council of the bishops in his lands to discuss how to dismantle the Arian church in Burgundy, but the honeymoon period for the new king was short. He fell out with his bishops, and his second wife manipulated him into murdering his own son. That’s the story we’re given anyway, and I mentioned it earlier in one of the episodes about Theodoric.

The upheaval proved a tempting opportunity for Clovis’ son Chlodomer, who attacked the Burgundians in 523 and quickly defeated the forces of Sigismund. Sigismund and his family were killed, but his body was retrieved and taken back to a monastery he had founded at Agaune, where it became the focus of the very first cult of a royal saint. The Burgundian cause wasn’t dead yet, though, as Sigismund’s brother Godomar appeared at the head of an army, part of which he had borrowed from Theodoric the Great. Our old friend Theodoric was well into his grumpy period and probably had just about had it with Frankish shenanigans on his doorstep. Godomar and his army met the Franks at Vézeronce, about 30 miles east of Lyon. Chlodomer was killed in the battle, and Godomar became the new king of the Burgundians – while owing a debt of honor to Theodoric, of course. A helmet was found near the battle site in the nineteenth century; it’s a beautiful piece of Eastern Roman workmanship, probably belonging to a chieftain on one side or the other of the conflict. It’s currently in the Musee Dauphinois in Grenoble, and I’ll obviously put a picture of that on the website and instagram.

Chlodomer’s story has its own tragic coda. His children lived with their grandmother Clotilde, until their uncles Chlothar and Childebert conspired to divide Chlodomer’s domain up between them. That would obviously, regrettably, require the elimination of the inconvenient nephews. Two of Chlodomer’s three sons were murdered, the third, Clodoald, escaped and fled to Provence. He made a more permanent escape when he renounced all his temporal titles and worldly wealth and became a hermit and preacher. He thus seemed to be no threat to his Frankish relatives, and he was able to return to Paris. Eventually he found a nice hill for himself next to the Seine, downstream from Paris, where he retired to pray in solitude. He built a church there, and both it and the town that grew up around it were named after him. Today it’s known as Saint-Cloud, which listeners to Mike Duncan may remember as the site of one of the Bourbons’ royal hunting lodges, and is today one of the wealthiest towns in France.

Let’s abandon the green fields of France and head down toward Spain. Not the clear blue waters of the Mediterranean, nor the baking interior, our first stop will be the northwest corner, where mountain valleys and canned seafood proliferate.

Waaay back when, those of you with very big brains may remember that the Vandals, on their way to Africa, were accompanied by two other tribes, the Iranian Alans, and the Germanic Suevi. The Alans accompanied the Vandals across the straits, while the Suevi stayed in Spain and eventually carved out a kingdom for themselves in the northwest. They’re still there, wedged up in the mountainous northwest of the Iberian peninsula, with a kingdom centered on Braga in modern Portugal.

I haven’t mentioned them for the very simple reason that after about 470, almost nothing is known about their political history. They were diplomatically active in those years, maintaining relations with the Visigoths, Romans, and Burgundians, but they were simply too peripheral for the chroniclers of the time to take much notice of them. The kingdom’s highpoint was around 455, when their influence stretched all the way down to Malaga. By the 510s though, conflict with the Visigoths and rebellion by local Roman elites had pushed them up into the territory of modern Gallicia and northern portugal. We don’t even know the names of their kings from about 470 to 550. Our primary source, Isadore of Seville, tells us only that there were a lot of them and that they remained, like the Visigoths, Arians.

We left the still proudly Arian Visigoths in disarray after defeat at Vouille and the death of Alaric II. In the immediate aftermath of the battle, the most pressing issue was succession. Alaric had one young son with his wife Theodegotha, the daughter of Theodoric the Great. Young Amalaric, for such was his name, was only around five years old when his father died. The Visigoths were reluctant to support such a young king in a time of crisis, so an alternative was found instead. Gesalic was also Alaric’s son, though illegitimate, in his mid twenties he was at least credible as a leader of armies, and the Visigoths elected him as their new king. It wasn’t what you would call a plum job, attempting to reorganize the Visigothic kingdom in the face of massive territorial loss and continuing Frankish aggression. Gesalic hung in there for about three years, but in 510 Theodoric sent an army to invade in the name of young Amalaric, who was after all, his grandson.

Gesalic was forced to flee to Africa, but got very little help from the Vandal kings, who were in no position at the time to stand up to Theodoric. Gesalic scraped together a few men and made a last ditch attempt to return to the Visigothic throne, but was defeated again. He retreated to Burgundy, where he was murdered. Theodoric, as we know, declared himself regent for Amalaric. The territories were ruled by a prefect named Steven, and it appears that he was able to retake some Gallic territory from the Franks, specifically in Gascony.

In spite of what appears on the maps, the Visigoths had not spent much time or effort pushing their influence into the Iberian peninsula very deeply. There were certainly Gothic garrisons in some towns, but that’s not the same as full administrative control of a region. The reality seems to have been a patchwork of semi-independent city-states, run on Romman models by the old Ibero-Roman elites. The tenuous control of the Visigoths is demonstrated by the entry for 494 in The Chronicle of Saragossa, which notes that in that year “The Goths entered Spain”. Since the Visigoths have had some presence in Spain since 418, this seems an odd thing to take note of, unless that presence had been particularly light, and only now did an influx of new Gothic settlers appear and begin to increase their influence. The chronicle records several “tyrants” who were overthrown and executed by the Goths. These were probably the local powers that were rivals to the Visigoths’ gradually expanding power in the region.

Even after Vouillé, the center of Visigothic gravity remained the coastal strip from Tolosa to Narbonne, with influence up the Ebro Valley and along the foothills of the Pyrenees. It’s a reminder that the solid blocks of color that we’re used to on a map are often a woeful oversimplification of political realities on the ground. In the absence of strong outside authority, the old landowners of Southern Spain did their best to carry on governing themselves as they had before. Over time Visigothic influence would grow, but tensions between the Arian military elite and the Catholic civic elite would remain for the next four generations.

Back up north, in a completely logical way, to the far side of the Rhine, in what the Romans used to call Greater Germania, and was now being absorbed by the Frankish kingdoms.

The Thuringians and Alamanni, faced with the seemingly unstoppable onslaught of Frankish aggression, were forced to come to terms with new realities. As always we have to remember that these were confederations of smaller tribes, and the existence of a Thuringian king does not necessarily indicate a unified Thuringian people. So some of the Rhinelanders (a word I decided just now to use for the two collectively – also a town in northern Wisconsin.) submitted to Frankish hegemony, while others, especially those up against the Alps, looked to Theodoric for support. Theodoric was happy to have them as a buffer against both the Franks and the hodgepodge of other Germanic tribes to the east. He promised support, and in return, they would guard the mouths of the mountain passes that led into Italy.

Beyond the Rhinelanders, the picture is as confused as it has ever been. The upper Danube valleys and the future lands of Bohemia continued to be fought over by various Germanic barbarian groups, coalescing and forming new identities as conditions shifted. A new round of confederation seems to have been underway, and a new generation of tribal names are beginning to become visible in the region. The Herules and Rugii remain, if you remember them, but they’ve now been joined by Bavarians and Lombards, there are still a few Vandals running around too, those that opted not to migrate at the beginning of the fifth century. Further to the north, the Saxons seem to be growing in strength, along with Frisians, and further north still, the Angles and Danes, and maybe the Jutes, though where exactly the Jutes came from is a bit of a mystery for another time. These tribes are effectively the next generation of barbarians. They will repeat the cycle of putting pressure on the Germanic kingdoms’ borders, just as their forebears put pressure on the Roman Empire.

Down the Beautiful Blue Danube, the Gepid kingdom occupied the majority of the future Hungarian plain. I don’t have much to add to their story from what we’ve already heard. The city of Sirmium was a bone of contention between the Gepid kingdom and Theodoric the Great, who eventually retook it. Sirmium was the hinge on which the Danube frontier had once turned, and still guarded the approaches to Italy from the East and northeast. Even without the former Roman capital, the Gepid kingdom was strong enough to offer protection to the Herule tribes, who were feeling the pressure from those newcomers, especially the Lombards. The Gepids also enjoyed overall good relationships with Constantinople. Gepid soldiers served in the Eastern army, trade was strong, and their kings grew rich.

Further east, over the Carpathians, and we’re once again on the steppe. Out there the swirling, bewildering array of horse-peoples out of which the Huns once appeared still remains. There still were Hunnic tribes active on the plains, and they were still willing to sell their services to any commander who might want them. Other tribes were there too, but none had yet reached a level of cohesion to be a threat to any of their neighboring kingdoms, beyond the kind of border raiding that was just a part of life for the settled people at the edge of the great grass sea. That will change soon, though. One group to note just for interest’s sake, is the Goths of Crimea, still there, still Gothic; a reminder that none of the migrations we’ve heard about and will continue to hear about were all or nothing.

The general eastward drift this episode should make the next destination on our tour clear: Constantinople. I said a while back that I wasn’t planning on spending much time on the details of what was going on over there, partly because I can only do so much, mostly because Robin Pierson’s History of Byzantium has it all covered admirably. I do feel the need, though, for those of you that have not listened to that excellent and now venerable podcast, to bring you up to date on the general outline of what has been happening in the remaining provinces of the Roman empire.

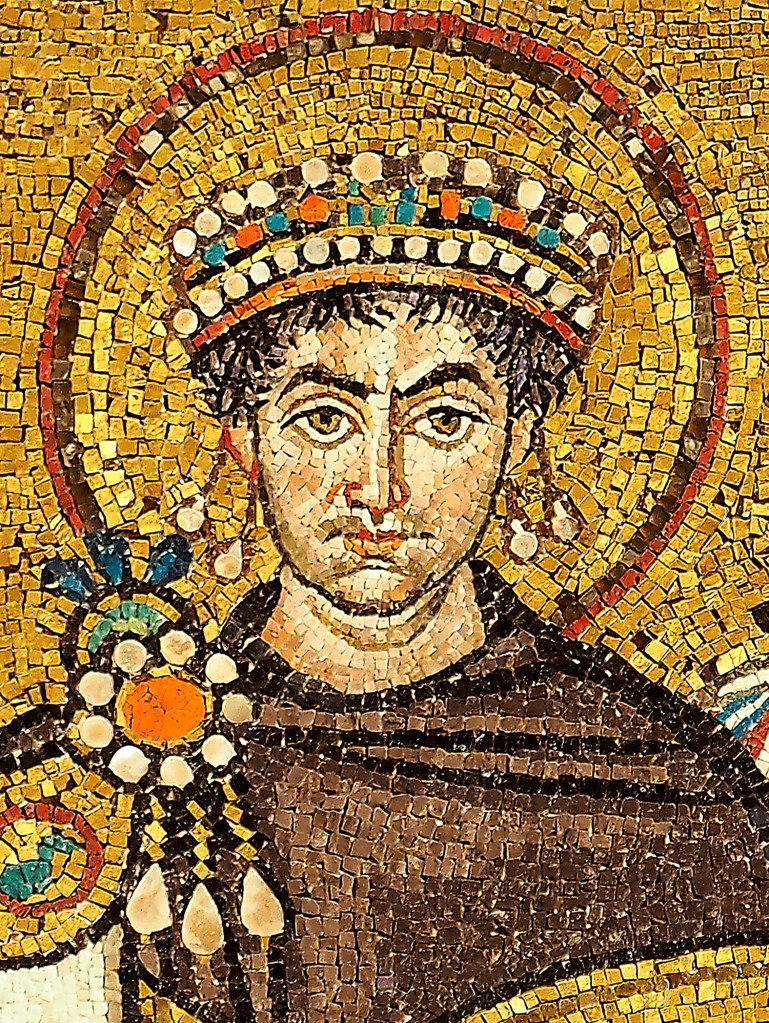

I wondered how many episodes I would need to write before I started forgetting what I have and haven’t told you. 35, it turns out. Looking back at my scripts, I see that I gave a pretty good accounting of how Anastasius had come to imperial power, but little about his actual reign. He was an old man – in his sixties, when he was passed the diadem, and had a reputation for being a bit of a stick in the mud. Much of his military attention was focused eastward, on the Persians, and on rebels in Isauria, which went a fair ways to keeping him off of Theodoric’s back. A monophysite, he was out of step with much of the church, including the pope, which probably also helped Theodoric, by keeping the pontiff from feeling too compelled to fight in the emperor’s corner. This was all part of the Acacian Schism, back in the episode titled Schism. If you can remember back that far, you may also remember that the emperor’s death in 518 went a long way to resolving that schism. That was good for the unity of the church, bad for Theodoric’s sense of security.

Anastasius left no heir. Palace intrigue and a pretty impressive bit of chicanery led to the elevation of Justin, the commander of the palace guard. Justin was impeccably orthodox in his faith, and he was quickly on good terms with the pope, and the Roman senate. You remember that it was a letter to the emperor that had indirectly led to the execution of Boethius, Justin was the intended recipient of that letter. The emperor kept up warm relations with the Frankish kings, and with the Burgundians. It all made the Ostrogothic king very nervous.

Justin had been a career soldier in the East, but by birth he was a latin-speaking peasant from Illyricum. As the local boy made good, as he climbed the ranks, Justin made sure that his family benefited from his success. He brought many of them to live in the capital and found them jobs. He was especially impressed by one of these relations in particular, his nephew Petrus Sabbatius. He adopted the boy and made sure that he got a first rate education and all the career help he could get. As was Roman tradition, Sabbatius added a name to honor his benefactor, the name we know him by; Justinianus. When the ultimate elevation came Justin’s way, Justinian was made an officer in the palace guard, and spent most of Justin’s reign at his uncle’s shoulder, clearly being groomed for even higher office. Justin would die just a year after Theodoric, and Justinian succeeded him. And that would have truly momentous consequences for the barbarian kingdoms.

All that remains for us to discuss, then, is Africa. I’m actually going to hold off on describing a lot about the development of the Vandal kingdom because that’s where I plan on picking things up when I get back. However, somebody in a review asked for more information about the situation in Mauritania, the lands to the west of the province of Africa, and here seems like a good place for it.

Before the Vandals arrived, the north coast of Africa was divided between the coastal towns, surrounded and sustained by arable farmland, and the hills and mountains to the south, which divided the coast from the desert. The further inland you went, the less settled the lifestyle became. Farmers gave way to shepherds and goat herders who moved back and forth between winter and summer grazing territories, who then in turn gave way to the fully nomadic tribes of the desert, who lived by trading and raiding. Ethnically the Berber-speaking people of the region were described most often as Mauri, from which derives the names of the two western provinces – Mauritania Tingitana and Mauretania Caesariensis, and the english word Moor, as in Othello. Mauri cavalry served regularly in the late Roman field armies, and Saint Augustine was ethnically Mauri. The histories I read usually just call them Moorish peoples, and I will probably use Mauri and Moorish interchangeably as we go along.

Not all Mauri were Roman subjects, most of the nomads and semi-nomads of the interior were also Berber-speakers – the ancestors of the modern Tuareg people – and that right there is a rabbit hole into which I peered and then quickly retreated from, lest we be here all day.

During the height of the Pax Romana, frontier fortresses were maintained along the edge of the desert and raiding was kept to a minimum through careful management of trade and tribute. The nomad kings, like frontier kings elsewhere in the empire, were eager for the recognition of the Roman state. Just as elsewhere, it increased a leader’s prestige and legitimacy to be the one to whom Rome came when they needed something. All the same, the southern frontier was never as clearly delimited in the South as it was in the North or east, where there were walls and rivers. How far the empire extended, really, depended on how far the fortress garrisons were prepared to venture on their patrols.

As the empire entered crisis, that began to change. As western resources were more and more tied up in defense of the northern frontiers, imperial authority became less and less evident in Mauritania. There was only one field army stationed in the region, and it was based in Africa, a long way from Morocco. It’s hard to say exactly when Mauretania was lost to Roman control entirely, or even what that might mean in practice. Was it when Ravenna stopped collecting taxes? Or when Ravenna stopped answering letters? The city of Volubilis in Morocco fell to local tribes as early as 285 and was never retaken. Certainly once the Vandals arrived, the whole of the Maghreb was beyond Roman influence, and would remain that way.

The Vandals didn’t stay though. They pushed on to take Carthage and the richest farmlands of Africa proper, as we know. There simply weren’t enough of them to contemplate holding such a lengthy strip of land, so they consolidated their holdings around the richest parts of modern Tunisia, and left the Western Provinces to do the best they could.

What that meant in practice is very difficult to discover. There are no written sources that deal directly with the region in the period, we have to tease what we can out of other writings, especially Procopius’ history of the Wars of Justinian. Archaeologically, we see changes that we’ve seen elsewhere, town forums shrinking, being impinged upon by residences for the wealthy, as public life becomes less and less important. Public baths held on longer in Mauritania than elsewhere in the empire, it seems, with some towns maintaining and even rebuilding their bathhouses into the middle of the seventh century. That’s not too surprising, I suppose, it’s hot down there. There’s another explanation too, bathing is often seen as central to Roman culture. Christianity, uncomfortable with nudity, had begun to make a dent in its importance, but its survival in the African provinces can be interpreted as a survival of Roman identity.

The political situation, as near as we can make out, seems to fit with that interpretation. The Roman towns became centers for new kingdoms, with native Mauri leaders, setting up a situation much like those in Italy and Africa – a barbarian army supported by Roman tax collectors. We don’t know how these kingdoms came to be created, how they interacted with each other, and we’re even unsure of how big they were and how many there were of them. Our only evidence for them is inscriptions, which are by their nature only brief snippets. Some of these leaders may have been from among the nomads, but some may have been former imperial officials of one kind or another. One, named Masties, declared in an inscription that he had been “Dux of the Moors” for 67 years, and “imperator of the Moors and Romans” for 10. “Imperator” of course, means emperor. He proclaimed himself a Catholic Christian around 476, possibly as part of a rebellion against the Vandals. Masties’ empire, if that is what it can be called, was centered on Arris, in modern Algeria, and may not have extended much beyond its own river valley. Another kingdom, at Altava, is known through an inscription dedicated to one Masuna, referred to as rex gentium Maurorum et Romanorum – King of the Moorish and Roman People. That same inscription lists officials of Masuna’s reign, all Moorish names with Roman titles. It’s the same story for other Berber kingdoms, uncertainty, other than the continuation of a Roman identity, welded to an increasingly prominent Berber one. Some of these polities would be absorbed later in the sixth century by Byzantine expansion, while others would maintain their independence until the arrival of the Muslims, but alas, the traces they left are not enough for us to reconstruct their whole story. I will put up a map of the important towns and sites of the region on the website and on Instagram.

When I come back I will be bringing you the tale of how the Eastern empire tried to bring back what had been lost. There will be war, glory, vainglory, and tragedy. Until then, thank you for listening, and take care.

References

Bowersock, Glen W. 1999. Late Antiquity: A Guide to the Postclassical World. Edited by Glen W. Bowersock, Peter Brown, and Oleg Grabar. N.p.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Fletcher, Richard. 1998. Barbarian Conversion. N.p.: Henry Holt and Company.

Frassetto, Michael. 2003. Encyclopedia of Barbarian Europe: Society in Transformation. N.p.: Bloomsbury Academic.

Geary, Patrick J. 1988. Before France and Germany: The Creation and Transformation of the Merovingian World. N.p.: Oxford University Press.

Gregory of Tours. 1974. The History of the Franks. Translated by Lewis Thorpe. London: Penguin Books.

Halsall, Guy. 2007. Barbarian migrations and the Roman West, 376-568. N.p.: Cambridge University Press.