November 536 to March 538

Belisarius continues moving up the Italian Peninsula, to bring his army to attack the greatest prize: Rome itself.

Belisarius was worried.

Sure, he had just taken the City of Naples after a three week siege. Yes, he had just marched up the southern third of Italy and brought it back to the Empire, hardly breaking a sweat. And yes, the breadbasket of Sicily had, if anything, come even more easily. It had been a busy and successful year for the general.

But still, Belisarius was worried.

The next logical step in the reconquest of Italy was the City of Rome itself. A shadow of its former self, nonetheless Rome remained politically and symbolically important, a huge propaganda prize if taken. It was November, winter was drawing in; the thought of sitting in tents outside the walls of the Eternal City in the cold was not an attractive one, especially with an army that was just barely big enough to do the job. He really had no choice, Rome would have to be taken, and as quickly as possible. It was just a matter of preparation and guts.

While Belisarius was sorting himself out in Naples, the Goths were making their own plans. Their new king Vitiges was a soldier and a strategist, and made the argument that discretion was the better part of valor. The Gothic forces in and around Rome were insufficient to stop the march of Belisarius as they were. A large fraction of their fighting men were away in Gaul, fighting off incursions by the Franks (which had been incited by Justinian, by the way). Better to resolve that fight, concentrate forces in Ravenna, then turn and face the Roman aggressors with the Goths’ full strength. The Goths around him approved this plan, and Vitiges led most of his army over the Apennines to Ravenna. He left Rome in the care of a garrison force of 4,000 and Silverius, who happened to be Pope.

Silverius had been consecrated Bishop of Rome during Theodahad’s brief reign, and only been in office a few months. He was very much in the Gothic pocket.

Believing that he had done the best he could for his interests in Rome under the circumstances, Vitiges rounded up most of the Senators of the city to keep as hostages, and set out for Ravenna.

Vitiges’ great problem, aside from the foreign armies that were stomping all over his fields, was dynastic. He had been elected by the Ostrogothic Nobility and had their confidence, but a little extra legitimacy could be nothing but helpful. With that in mind, when he arrived in Ravenna he married the now 18 year old Matasuintha, daughter of Amalasuintha and last remaining member of the House of Amal. The wedding was very much against the lady’s will, according to Procopius, but Vitiges felt he needed the connection to Theodoric. The two would have no children, and we’ll check in on Matasuintha later on in our narrative.

Vitiges also hired the reliable Cassiodorus, who wrote him a panegyric, probably delivered to the assembled senatorial hostages. Who knows how that went over, but the tradition of casting Gothic kings in Roman molds remained alive and well.

Having done … all that … Vitiges gathered arms, equipment, horses, and men. He left the garrison troops in Gaul to guard against the Franks, but otherwise gathered the full power of the Goths in Italy to him.

Meanwhile, Belisarius was taking his time. He made sure that Naples and Capua were secure, as they were the only strongholds in Campagna, but left them the smallest garrisons he thought he could get away with, 300 men in the case of Naples. While he was thus engaged, he was approached by a man named Fidelius – a name so on the nose that I struggle to believe Procopius didn’t make it up.

Fidelius represented Pope Silverius. “General Belisarius, we’ve had a look at your resume and taken a bit of a poll around the city, and we’ve decided that yes, you can have the city, please wipe your feet before you come in.” I’m paraphrasing.

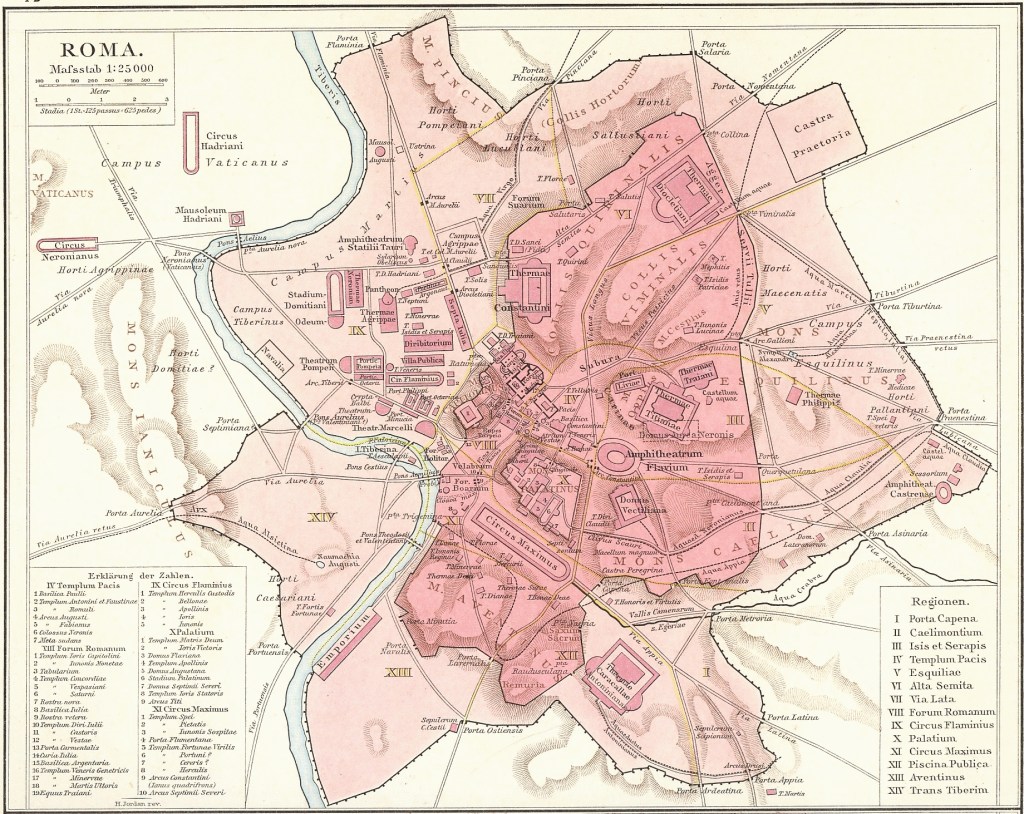

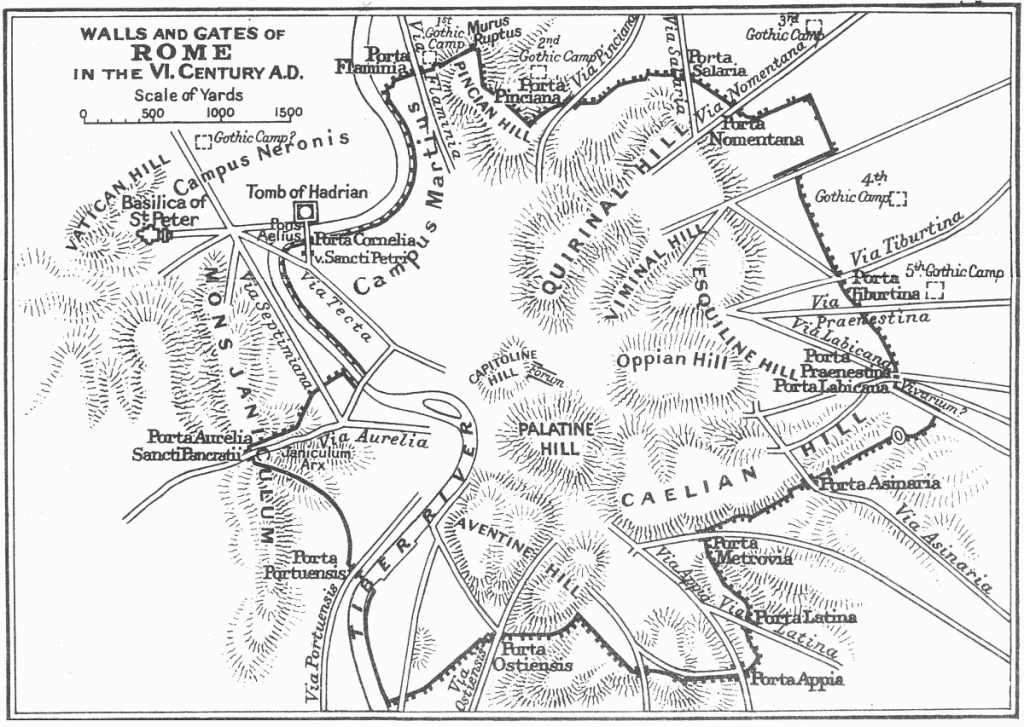

No one bothered to share this decision with the Gothic garrison until Belisarius’ army was nearing the city. “Uh, yeah, youse guys might wanna, I don’t know, make yourself scarce, if you knows what’s good for yah.” Given the obvious unwillingness of the citizens to defend the city against the Romans, the garrison exited stage left, pursued by bear. As they were leaving via the Flaminian Gate, Belisarius’ army entered through the Asinarian Gate. I’ll include a map of the city with the transcript for this episode on the website. Did you know I post transcripts on the website? Darkagespod.com, if you’re interested.

The Gothic commander, a man named Leuderis, stayed where he was, probably as a matter of honor, possibly out of fear of the consequences of failing to defend the city. Belisarius took him into custody, treated him with all respect, and sent him and the keys to the gates to Constantinople. (He kept copies of the keys, obviously, he wasn’t an idiot.) On December 9, 536, the eternal city came back into the control of the Roman empire. Sixty years had passed since the deposition of Romulus Augustus.

It’s actually a little bit of an innaccuracy to say that things had returned to a preexisting status quo. The City of Rome, indeed, Italy in general, had never been under the direct rule of the Emperor in Constantinople. An argument could be made that it was so under the reign of Theodosius I, but that was only for a few months, and that was 140 years ago now. The new reality would take some getting used to, and the Roman’s joy at Belisarius’ arrival immediately received a splash of cold water when he began work on repairing and improving the city’s circuit walls. Avoiding a siege had been the whole point of letting Belisarius in in the first place, but here he was, very clearly planning to resist just such a thing.

I’m … honestly not sure how they didn’t see that coming.

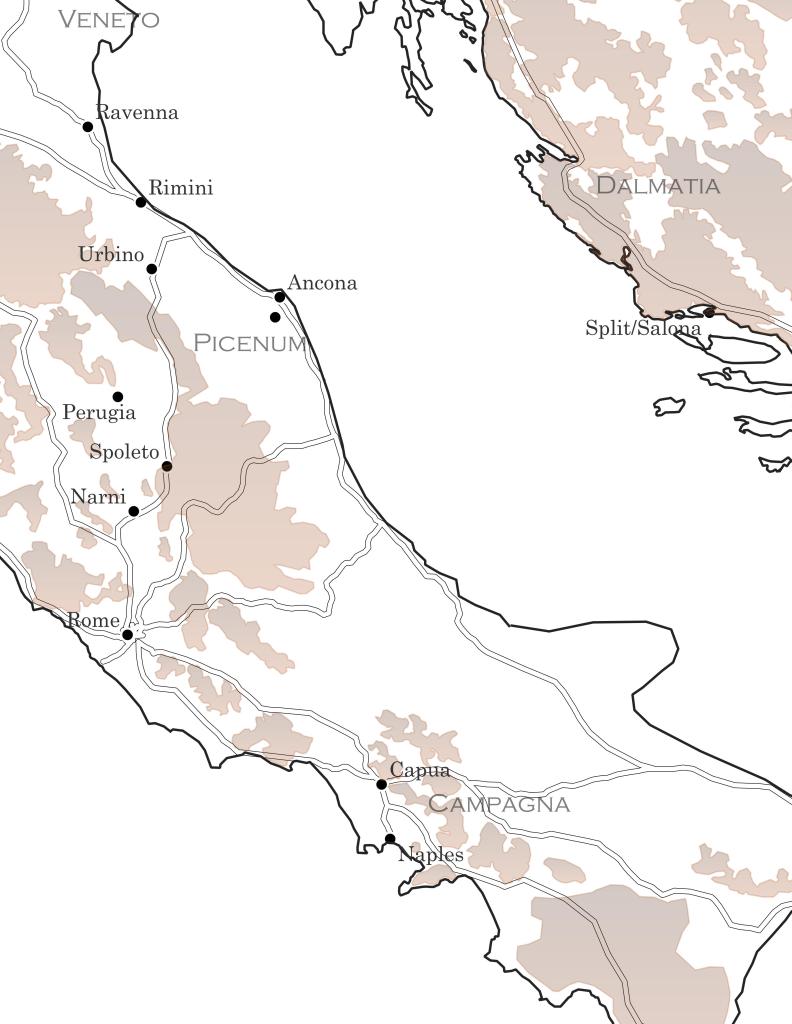

Along with preparing Rome for the inevitable return of Vitiges, Belisarius sent messages to the emperor reporting his success and requesting reinforcements, and continued to extend his hold over the Italian countryside. He sent a detachment under a commander named Constantinus, and another under a Thracian Goth named Bessas, to head north into Tuscany. The towns they encountered opened their gates to them without any trouble, and very shortly Roman control extended to Perusia and Spoleto in Tuscany, and the town of Narni, in Umbria. Vitiges attempted to contest the Roman movements, sending an army against Perugia, but they met the Romans in battle and were soundly defeated .

Vitiges decided he needed to kick things into high gear. News of the defeat at Perugia made him restless. He felt he could no longer wait to gather more reinforcements, but would have to make a decisive move. He dispatched an army north, to gather troops from beyond the border and make an attempt at re-taking Dalmatia, while he himself gathered a larger force, and moved toward Rome.

That mission north is interesting, since according to Procopius, the commander was to travel to “the lands of the Sueves” looking for allies. At first I thought he was going all the way to the Suevic kingdom in northwestern Hispania, which seemed inefficient. Then I remembered that ancient writer’s trope of using the historical name rather than the current one for places and people, as we saw when authors referred to the Huns as Scythians. Procopius was talking about the region we would call Bohemia, onetime home of the Suebi, along with the Vandals and others. The troops he was recruiting were most likely people we haven’t talked about yet, and who we will have reason to return to, the Langobardi, aka the Lombards.

The combined Gothic and Lombard armies assaulted Dalmatia and laid siege to Salona, and we will come back to them later. Because at the same time, Vitiges was hurrying toward Rome. He had heard that the force remaining in the city was small, and he wanted to trap them in the city. He worried that Belisarius would run away when he heard that the Goths were coming, and deny him the victory.

He had misjudged his man. Belisarius was ready for him. He recalled Bessas and Constantinus, ordering them to leave minimal garrisons in the cities they had captured, and return with the rest of their armies to reinforce him. When Bessas arrived, he brought news that the Goths were right on his heels. The gothic army, according to Procopius, numbered over 100,000, which is ludicrous, and we are entering a section of the narrative where Procopius cannot help but draw parallels to the Iliad, and let his inner Homer out to play. Modern estimates put the Gothic army around 25 to 30 thousand.

This seems like an excellent time to pause and consider what Belisarius was defending exactly. What did Rome look like in the winter of 536-537?

I’ve been very careful to avoid numbers whenever possible in this show, because everything is extremely conditional and never better than an educated guess. That said, the best educated guess is that at its absolute height under the empire, the walls of Rome contained a population of around 1,000,000 people, nearly half of whom were slaves. The successive crises of the third and fourth centuries: plague, famine, economic depression, and civil war, had steadily decreased the population to an estimate of between 500 and 750,000 citizens in the year 400. Compared to that relatively gentle whittling down of population, the fall of the West was catastrophic for the city. By 500, in spite of the patronage of Theodoric and the Pope, Rome’s population had fallen to between 75 and 100,000, a drop of almost 90% in the space of a century. Economics were probably the most important driver of the change. As imperial focus moved away, the vast bureaucratic apparatus moved with it, removing the customer base for the many many artisans, merchants, and laborers who kept it supplied. The phenomenon of the flight of the curiales, which I’ve talked about before, as local elites focused their attention and economic inputs away from the cities and into their own large estates, affected Rome just as it did the other urban centers of the empire. A fair proportion of material wealth was also removed by the Visigoths, even more by the Vandals, and when Belisarius recovered some of this treasure, it went to Constantinople, not back to Rome.

We can imagine then that while real estate prices probkably dipped as demand cratered, it didn’t represent an opportunity for urban renewal. City services and maintenance fell off, not really due to neglect, but due to the absence of an adequate workforce and tax base – a situation that residents of Detroit are familiar with. That being said, the sewers continued to be cleared, the aqueducts continued to run. Many bathhouses were shuttered, but not all of them, and the ones that remained open continued to be a center of secular urban life. The most basic infrastructure remained, though perhaps not as shiny as it had once been. I hope that you can hear the foreshadowing in my voice.

Back to the action.

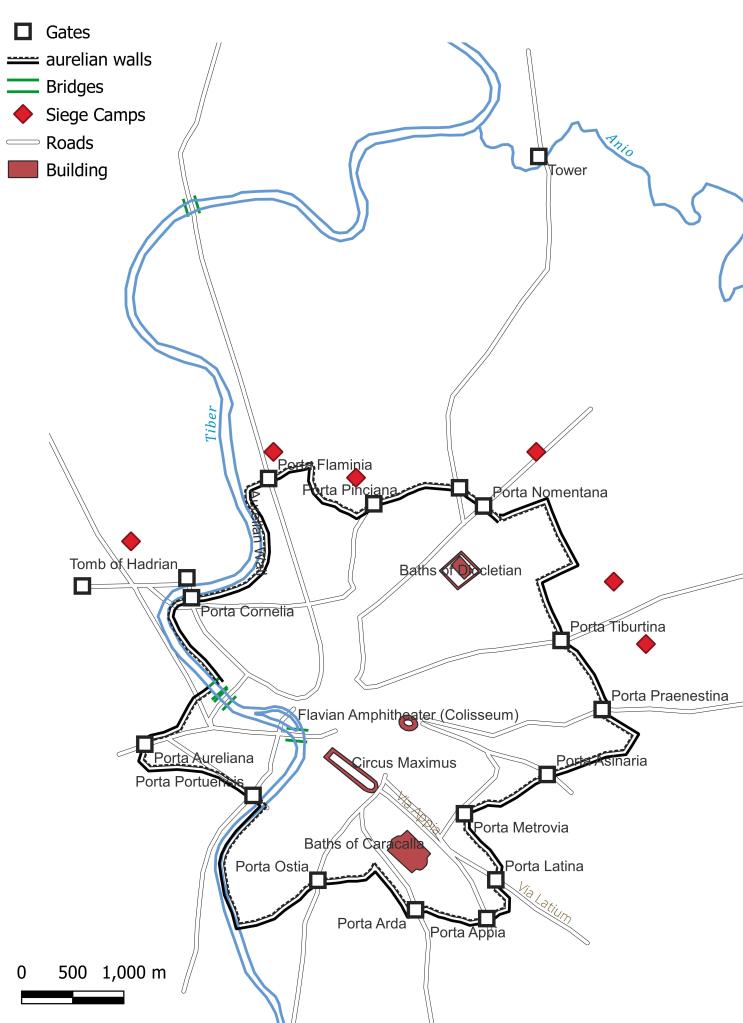

With the Goths approaching, Belisarius did everything he could to slow them down. He had had a tower and gate built to protect the bridge that carried the Salerian Way over the Anio River, about two miles north of the city. I am absolutely going to put a map together to supplement the one on Wikimedia, and I’ll link to both in the show notes for this episode. I highly recommend taking a look at them, it will make all of this much much clearer.

The Anio is a small and fairly benign river, easy to cross in normal circumstances. Heavy rain, though, had raised the water level, and so the bridge took on added importance. When the garrison that had been left in the tower caught sight of the Gothic army, they slipped away in the night, and Vitiges was able to cross unimpeded. Within sight of Rome, the Goths rushed forward, but met a force of about 1000 cavalry, led by Belisarius himself, who had come out to observe the enemy’s movements. Belisarius was forced to fight, and in the heat of the moment placed himself at front. He was in even more danger than would normally be the case, since his horse was apparently quite distinctive and had been made well known to the Gothic warriors. Every projectile was aimed at the general. Procopius waxes lyrical about his commander here:

“…every man among them who laid any claim to valor was immediately possessed with a great eagerness to win honor, and getting as close as possible they kept trying to lay hold of him and in great fury kept striking with their spears and swords. But Belisarius himself, turning from side to side, kept killing as they came those who encountered him, and he also profited greatly by the loyalty of his own spearmen and guards in the moment of danger … holding out their shields in defense of both the general and his horse, they not only received all the missiles, but also forced back and beat off those who … assailed him.”

Both sides took losses, but by some stroke of luck – the friend of all the great generals – Belisarius was unhurt. The sheer weight of numbers forced the Romans to fall back to the Salerian Gate, with the Gothic cavalry in pursuit. The men on the wall refused at first to open the gate, unable to recognize their general, he was so covered with dust and blood, and convinced that he had fallen in the fighting. Belisarius was forced to make another charge back the way he had come, taking his pursuers by surprise and driving them back. He then returned to the gate, removed his helmet, and was finally admitted into the city.

In his eagerness to tell a good yarn, Procopius does not neglect the honor or bravery of the other side. In an aside, he tells the story of a Goth called Visandus, who was one of the first to bring the fight to Belisarius, and who fought ferociously until he received 13 wounds, and fell. He was left among the dead on the field until three days later. The Goths, collecting the dead for burial, found him and discovered that he was alive. He was given food and water and carried back to the Gothic camp, and became a famous warrior among his people.

On the night after this initial skirmish, Vitiges sent one of his commanders to approach the wall. He called out to Belisarius, telling him that his men were inside the city already, all was lost, and that the Romans should leave before they were completely overrun. Many panicked, but Belisarius immediately declared the news false. Scouts were sent out to make a circuit of the walls, and reported that not only were the Goths not in the city, they had not even reached the part of the walls they claimed they had taken.

It was an example of an ongoing campaign of psychological warfare waged on both sides throughout the siege. Another Goth was sent by Vitiges to call out to the Roman citizens, chastising them for betraying the Goths who had been their rulers for so long. These Greeks couldn’t even defend them, he said, look how few of them there are, and how many of us? Could a Greek even be a soldier? He wondered, the only Greeks he had ever seen in Italy before were all actors, mimes, and pirates, the lowest of the low, and certainly no fighters.

It’s an interesting point that Procopius reports the use of the word “Greek” for the men of the East as entirely unremarkable or worthy of further comment. Going forward, the Latin west will be consistent, both in its use of the term Greek to describe the people of the east, and in the connotation that those people were decadent, unmanly, and not to be trusted. The cultural division that was already present before the fall of the West was widening, and it would only continue to do so in the coming centuries.

The first day of the siege thus ended exactly how we might expect. As evening fell, Belisarius ordered fires built and a constant watch kept along the walls. When that was done, he was finally prevailed upon by his wife to eat something, for the first time that day. At all times over the coming weeks, and indeed months, Belisarius would maintain a positive attitude, ever confident of success. Vitiges and the Goths, meanwhile, spread themselves out around the circuit of the walls, and began to set up their camps.

The Aurelian walls which had protected Rome since the 270s enclose an area of 13.7 square km, 5.3 square miles, behind 12 miles of brick and Roman concrete. In the year 500 they were pierced by 23 gates of varying size and importance, and augmented by 383 towers.

All very impressive sounding, but for Belisarius, they presented a problem. Maybe you’ve spotted it already. Counting the reinforcements he had conscripted from the city itself and the countryside, Belisarius held Rome with perhaps 12,000 men at most. If he spread them out evenly around the walls, that would be one man every five feet. Which theoretically sounds okay. But he couldn’t spread them all out evenly all the time. The officers and bucellarii didn’t do sentry duty, and soldiers need to sleep, and eat, provisions need to be guarded and distributed, the streets patrolled and kept safe, messengers and scouts needed to be available. With all of that taken into consideration, the Aurelian walls start to seem like more of a liability than an advantage.

The Goths set up six camps on the east side of the Tiber, opposite the primary north-facing gates, and one more on the west, between the Vatican hill and the river. In spite of his massive advantage in numbers, Vitiges did not have enough men to completely surround the city. (More evidence that Procopius’ figure of 100 thousand is an exaggeration.) The south-facing gates remained unguarded. Both sides settled in for a proper siege. Belisarius ordered most of the minor gates bricked up, as Vitiges’ men set about breaking all the fourteen aqueducts that fed the city. Mindful of the events that had delivered Naples to him, Belisarius had the aqueducts inside the walls sealed with sturdy masonry, to prevent anyone entering that way.

For the moment, the loss of the baths were merely an inconvenience, since like Naples, there were plenty of wells inside the walls for drinking water. More problematic was the loss of the grain mills that had been turned by the aqueducts. That was a real problem, since all the grain stockpiles in the world would be useless if they couldn’t be turned into bread. The solution to the problem was ingenious. The Tiber passes through the walls, and a bridge spans it just below that spot. The Romans moored two boats just downstream from the bridge, where the water flowed with considerable force between the pylons. They were set two feet apart, and a wheel mounted between them which was turned by the river and ran a mill set on each boat. Once it became clear that this arrangement would work, more boats were placed in a similar arrangement, and the city’s flour problem was relieved. The Goths attempted to put a stop to these river mills by throwing logs and other debris into the River, but Belisarius stretched a chain across the river above the bridge, and the mills kept turning for the remainder of the siege.

A siege is, most of the time, defined by boredom, punctuated by sudden stresses. The soldiers were familiar with the routine, but the civilian population was not. Many were conscripted into guard duty, which they found dull, and they were unused to the shortages and privations that came with a blockade. I can just imagine some corpulent merchant, sweating in the sun on the parapet, whining about the closed bathhouses to an uninterested Thracian soldier as they watched the Goth foragers pillaging the surrounding farms and fields.

Dissatisfaction with Belisarius’ leadership became general among the civilian population. Some deserted the city entirely and went over to Vitiges’ camp, telling of the unrest that grew within the walls of Rome. Vitiges sent envoys to Belisarius, and the senate, and offered the general an out, he would allow the Romans to leave with all their possessions, since they surely must be regretting so rash an action, to take the field against the Goths with such a small force? They also rebuked the Romans again, for betraying their rulers, the heirs of Theodoric, who had done so much to foster their prosperity and wealth. The unflappable Belisarius, you won’t be surprised to hear, remained unflapped, and the senate sat in stony silence, caught as they were between a rock and a hard place.

The ambassadors returned to Vitiges to give their report on the meeting, and probably of greater interest to the king, on the character of Belisarius. Vitiges immediately began preparations for an assault on the walls in earnest.

The Goths built towers, ladders, and four battering rams. There would be no unintended hilarity like there had been during the Romans’ assault on Naples, the ladders and towers were constructed to the perfect size for their purpose.

Their preparations were not invisible, of course, and Belisarius made his own arrangements, placing balistae and onangers on the parapets, and traps behind the gates, in case any of them were broken into. If you’re not familiar, a ballista is essentially a giant crossbow which shoots heavy bolts. The onager is a type of catapult, powered by torsion. As described by Procopius, the version Belisarius used had a sling on the end of its throwing arm, and flung probably fist-sized stones. They were anti-personnel weapons, capable of taking out a handful of attackers at once, if they were standing more or less in a line. Best not to think about that too much.

On the 18th day of the siege, Vitiges was ready, and the assault began. Belisarius laughed when he saw the towers approaching, and ordered that no one was to so much as toss a rock until he gave the signal. He caught quite a bit of flack for this, as soldiers and conscripted civilians called him a coward who was trying to cover his fear with false laughter. (We’ll come back to Belisarius’ ongoing struggles to keep the respect of his subordinates in a later episode.)

Once the Goths were within reach, Belisarius himself loosed the first arrow, killing his target (though Procopius concedes it was a lucky shot). All the other bows along the wall let loose, with Belisarius ordering them to aim especially for the oxen that pulled the Goths’ siege engines. The beasts fell quickly before the hail of arrows, and the towers and battering rams were rendered immobile.

His initial assault thus stymied, Vitiges gave orders to keep Belisarius busy where he was, while the focus of the attack shifted to the relatively short section of walls on the right bank of the Tiber, around the Mausoleum of Hadrian. The mausoleum had been incorporated into the Aurelian walls and stood at the head of the Aellian bridge and opposite the Cornelia gate. The building still stands today, known as the Castel Sant’Angelo. The funeral urns of emperors from Hadrian to Caracalla had been deposited there, but had been scattered by Alaric’s Visigoths in 410. The tomb effectively functioned as an additional tower along the walls, guarding the bridge. The defense of this section was given to a commander named Constantinus, who like most of the section commanders, would have appreciated more men. The goths feinted an assault on the riverside section of the fortress, and Constantinus rushed to meet them there, pulling forces away from the other parts of the walls. Goths who had been hiding nearby used the opportunity to scale the walls with ladders under the cover of heavy arrow fire. The defenders were hard pressed, until someone had the idea to break up the many statues that decorated the roof of the mausoleum and throw them down on the heads of the Gothic attackers. The Goths were driven back until they were at a sufficient distance to bring the fort’s balistae to bear, at which point they fled. So the attack was beaten back, but another remnant of Rome’s past achievements was lost.

Roman sorties drove similar assaults away from the Salerian and Prenestina Gates, and hard fighting continued into the late afternoon, when Vitiges finally called off the attacks. The Goths had taken heavy losses, and made no real progress. Belisarius and the Romans celebrated their victory, but the general wrote to Justinian that same night, pleading for reinforcements. The success of the day could be easily reversed, and he worried about the fortitude of Rome’s civilian population. “The Romans will be compelled by hunger to do many things that they would prefer not to do.” Belisarius had no illusions about the hardships that lay ahead.

As it happens, Justinian had already sent a relieving force, but it had been delayed by winter storms, and was waiting in Greece for the weather to clear. News of that force was able to make its way to Rome, which helped keep spirits up. The incomplete blockade of the city meant that the Romans were able to send women and children to safety in Naples. That wasn’t just to get them out of harm’s way, but to relieve some of the pressure on provisions. Belisarius was settling in for the long haul.

That incomplete blockade made it an oddly active siege, as raiding parties sallied out from the city regularly. These were both hunting Gothic foragers and foraging themselves, and their activities kept the Gothic armies mostly in their camps at night. Meanwhile in public Belisarius projected a positive attitude, and worked hard to keep up morale and maintain discipline. Civilians recruited as sentries on the walls were payed a small wage. It kept body and soul together in a city where all real economic activity had come to a halt. Every effort was made to stave off complacency and boredom; postings were changed regularly, and a man on the north parapet one night may find himself on the southeast the next. Commanders were changed too, to prevent favoritism. Moorish cavalry patrolled the outside of the walls, assisted by dogs, and musicians were employed to play every night to keep the guardsmen awake. Belisarius had the gate’s locks changed and old keys destroyed a couple times to prevent copies from being stolen by deserters.

Vitiges was no less active. The ease with which the Romans were keeping themselves supplied was a problem, and the Gothic king moved to pinch off the lifeline. He sent a force to Portus, the main harbor of the city. Belisarius had been unable to garrison the town, and the Goths took possession relatively easily, slowing the flow of supplies. Most supplies had to come overland from Naples.

The relief army heavily favored horse archers, and Belisarius used them to step up his extramural activities, with regular sallies to harass the Gothic siege camps. Confidence inside the city grew, and Belisarius came under pressure to risk a pitched battle and drive the Goths away from the walls for good. He resisted; even with the reinforcements, the numbers were still against him.

Eventually though he was forced to give way. The engagement got off to a good start for the Romans, as the Goths were driven away from their camps and into the surrounding hills. The undisciplined citizen conscri[pts, though, fell to plundering the Gothic camp, and were unprepared when Vitiges led a counter-charge. The Roman infantry fled in the face of the cavalry charge, toward the city, seeking refuge. The defenders inside worried that the Gothic pursuers would force their way into the city and the gates remained firmly shut. Many were killed between the moat and wall before the cavalry arrived to drive the Goths away. Though strategically a draw, the engagement was costly enough to harden Belisarius’ attitude against large-scale fighting for most of the rest of the siege. He resumed his hit and run raiding strategy, and refused all further calls for more offensive actions.

Time passed.

Then passed some more.

Surprisingly, after a little time, time continued to pass.

The siege took a toll on the inhabitants of the city. While supplies were not completely cut off, they were still drastically limited, and the soldiers took priority in distribution. By spring of 538, the city’s grain supply was completely exhausted, and many lived on the herbs that they could find growing wild inside the city walls. Some enterprising soldiers snuck out of the city and cut grain growing in the fields to sell back to the citizens at a premium. A black market in mule sausages sprang up. Unrest began to grow, and some Romans advocated for open battle again, not for military gain, but to have the opportunity to die gloriously rather than starve. Belisarius put them off, first chastising them for so lightly throwing away strategic advantage in hasty action, second because he had had word that a third imperial army was already on the way to relieve the siege, which, fortunately for him, happened to be true.

Life was not any easier in the Gothic camps. Sure their supplies were more regular, but they had spent the winter in tents, with open latrines. At least the Romans had the benefit of solid walls and a still mostly functional sewer system. Nonetheless, disease began to spread through both populations. Vitiges had been sending letter after letter to Constaninople to try and find a diplomatic solution, but these remained unanswered. He contacted Belisarius directly, and offered peace on terms of the status quo – in other words, he would surrender Sicily and the south – which he didn’t control anyway – in return for an end to the war.

It was an opportunity for a little bit of sarcastic banter. As recorded by Procopius, the Goths offer was presented thusly: “In order that we may not seem contentious, we give up to you Sicily, great as it is and of such wealth, seeing that without it you cannot possess Africa with any security”

Belisarius was ready with the reply, “And we on our side permit the Goths to have the whole of Britain, which is much larger than Sicily.” Good one, boss.

In the course of the discussion the Goths pointed out that they had not taken Italy from the Romans, but from the usurper Odoacer, thus the Romans could have no legitimate quarrel with them. Belisarius took the position that Theodoric had been contracted to remove Odoacer on behalf of the emperor, not to rule Italy himself. That was in line with the new policy position coming out of the great palace, as Justinian continued on his restorationist track. The Goths might have wondered aloud why the emperor had waited until now to contest Theodoric’s claim, but if so, Procopius did not record it. In the end the parties agreed to a truce of three months.

The truce was entirely to Belisarius’ advantage, and allowed him to bring the reinforcements sent by Justinian, who had landed at Naples, safely into the city. The tide was turning in the Romans’ favor. The Romans controlled the sea, and were able to blockade Portus, forcing the Goths away from the port city and making resupply of Rome much easier. Meanwhile, Vitiges’ men grew sicker and more exhausted. Belisarius was so confident that he organized an expeditionary force to move north east, into Picenum, commanded by a man named John. Not the John from the African campaign, you’ll remember he was killed, this is a new John. This John was to avoid confrontations, but if he was challenged, to capture whatever stronghold he could and hold it. Under no circumstances was he to leave any strong points in his rear.

Vitiges was aware that he had made a bad deal. In desperation he renewed attempts to take the city by force. An attempt to enter the aqueducts was detected and thwarted, as was a direct assault on the Pincian gate. The truce broken, Belisarius sent orders to John to move into Picenum openly. John ignored his orders about strongpoints in the rear, and bypassed the fortified towns of Urbino and Osimo, instead accepting an invitation from the Roman citizens of Rimini to enter and take control of that city.

The move spooked Vitiges. Not only did the Romans now control major ports on both sides of the peninsula, Rimini was only a day’s march from Ravenna. On 12 March, 538, the Goths abandoned the siege of Rome, and burnt their camps. They began to march back toward Ravenna. Belisarius wasn’t about to let them leave that easily. He waited until half the army was across the Milvian bridge, then gave chase. The Goths put up a strong rear-guard, but eventually broke and fled, with many killed or drowning in the river in the chaos.

After a year and nine days, the citizens of Rome were able to leave the walls of their city. It was no doubt a relief to escape into the open air, the lingering stench of Gothic latrines notwithstanding.

None of them could have known that in spite of the victory, the old Rome was dead. The aqueducts would never be restored. The baths would never reopen. Most of the thousands of people who fled the city would never return, and by the end of the Gothic Wars, Rome’s population would shrink to just 30,000.

Those Gothic wars were far from over, of course. Vitiges had withdrawn but wasn’t defeated. Hard fighting was still to follow, but for the moment Belisarius could bask in his victory.